AY Honors/Weather - Advanced/Answer Key

1. Have the Weather Honor.

2. Explain cyclonic and anticyclonic weather conditions and know how they bring about weather changes.

Cyclonic Systems

Extratropical cyclones, sometimes called mid-latitude cyclones, are a group of cyclones defined as synoptic scale low pressure weather systems that occur in the middle latitudes of the Earth having neither tropical nor polar characteristics, and are connected with fronts and horizontal gradients in temperature and dew point otherwise known as "baroclinic zones". Extratropical cyclones are the everyday phenomena which, along with anticyclones, drive the weather over much of the Earth, producing anything from cloudiness and mild showers to heavy gales and thunderstorms.

Extratropical cyclones can bring mild weather with a little rain and surface winds of 15–30 km/h (10–20 mph), or they can be cold and dangerous with torrential rain and winds exceeding 119 km/h (74 mph), (sometimes referred to as windstorms in Europe). The band of precipitation that is associated with the warm front is often extensive. In mature extratropical cyclones, an area known as the comma head on the northwest periphery of the surface low can be a region of heavy precipitation, frequent thunderstorms, and thundersnows. Cyclones tend to move along a predictable path at a moderate rate of progress. During fall, winter, and spring, the atmosphere over continents can be cold enough through the depth of the troposphere to cause snowfall.

Anticyclonic Systems

An anticyclonic storm is a weather storm where winds around the storm flow contrary to the direction dictated by the Coriolis effect about a region of low pressure. In the northern hemisphere, anticyclonic storms involve clockwise wind flow; in the southern hemisphere, they involve counterclockwise wind flow.

Anticyclonic storms usually form around high-pressure systems. These do not "contradict" the Coriolis effect; it predicts such anticyclonic flow about high-pressure regions. Anticyclonic storms, as high-pressure systems, usually accompany cold weather and are frequently a factor in large snowstorms.

Anticyclonic tornadoes often occur; while tornadoes' vortices are low-pressure regions, this occurs because tornadoes occur on a small enough scale such that the Coriolis effect is negligible.

3. What are cold fronts and warm fronts? How do they move and what weather conditions do they produce?

Cold Fronts

A cold front is defined as the leading edge of a cooler and drier mass of air. The air with greater density wedges under the less dense warmer air, lifting it, which can cause the formation a narrow line of showers and thunderstorms when enough moisture is present. This upward motion causes lowered pressure along the cold front. On weather maps, the surface position of the cold front is marked with the symbol of a blue line of triangles/spikes (pips) pointing in the direction of travel. Cold fronts can move up to twice as fast as warm fronts, and produce sharper changes in weather than warm fronts, since cold air is denser than warm air it rapidly replaces the warm air preceding the boundary. Cold fronts are typically accompanied by a narrow band of showers and thunderstorms. Cold fronts are usually associated with an area of low pressure, and sometimes, a warm front.

Warm Fronts

A warm front is defined as the leading edge of a mass of warm air. Warm fronts move more slowly than the cold front which usually follows due to the fact that cold air is more dense, and harder to remove from the earth's surface. If the warm air mass is stable, clouds ahead of the warm front are mostly stratiform and rainfall gradually increases as the front approaches. At the front itself, the clouds can reach the surface as fog. Clearing and warming is usually rapid after frontal passage. If the warm air mass is unstable, thunderstorms may be embedded among the stratiform clouds ahead of the front, and after frontal passage, thundershowers may continue.

In the northern hemisphere a warm front usually causes a shift of wind from southeast to southwest and in the southern hemisphere from northeast to northwest.

4. Explain the following weather conditions:

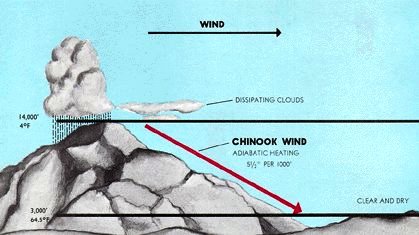

a. Chinook winds

Chinook winds, often just called chinooks, are winds in the interior West of North America, where the Canadian Prairies and Great Plains meet various mountain ranges. Southeast of the mountains, on the British Columbia Coast and in the Puget Sound area, it is a warm, very wet, southwesterly wind, likely to bring rain or snow. Northeast of the mountains, it is warm and dry, after being stripped of its moisture by the mountains in its path.

Chinook winds, often just called chinooks, are winds in the interior West of North America, where the Canadian Prairies and Great Plains meet various mountain ranges. Southeast of the mountains, on the British Columbia Coast and in the Puget Sound area, it is a warm, very wet, southwesterly wind, likely to bring rain or snow. Northeast of the mountains, it is warm and dry, after being stripped of its moisture by the mountains in its path.

b. Trade winds

The trade winds are a pattern of wind that are found in bands around the Earth's equatorial region. The trade winds are the prevailing winds in the tropics, blowing from the high-pressure area in the horse latitudes towards the low-pressure area around the equator. The trade winds blow predominantly from the northeast in the northern hemisphere and from the southeast in the southern hemisphere.

c. Belt of calms

The Belt of Calms is more properly known as the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). It is also known as the Intertropical Front, Monsoon trough, Doldrums or the Equatorial Convergence Zone, is a belt of low pressure girdling Earth at the equator. It is formed by the vertical ascent of warm, moist air from the latitudes above and below the equator.

The air is drawn into the intertropical convergence zone by the action of the Hadley cell, a macroscale atmospheric feature which is part of the Earth's heat and moisture distribution system. It is transported aloft by the convective activity of thunderstorms; regions in the intertropical convergence zone receive precipitation more than 200 days in a year.

d. Tornadoes

e. Squall line

f. Typhoons

g. Hurricanes

h. Blizzards

i. Ice storm

5. Explain the action of a registering thermometer, registering barograph, hygrometer, and an anemometer.

6. Correctly read a daily weather map as published by the National Weather Service, explaining the symbols and telling how predictions are made.

7. What is meant by relative humidity and dew-point?

The amount of water that air can hold depends on the temperature. The hotter it gets, the more water the air can hold. At any given temperature, the air can become so saturated with water that it cannot hold any more. Water will not evaporate under this condition.

The ratio of how much water is in the air compared to how much could be in the air is the relative humidity. The relative humidity is 100% when the air can hold no more water.

Recall that the air can hold more water when it is warm as compared to when it is cold. Therefore, if the temperature changes while the amount of water in the air remains constant, the humidity will change. As the air warms, the relative humidity will drop. As it cools, the relative humidity will rise.

The dew point is the temperature for which the relative humidity will be 100% assuming the amount of water in the air remains unchanged. If the temperature drops below the dew point, the air will no longer be able to hold all the water, so it condenses out in the form of dew or fog.

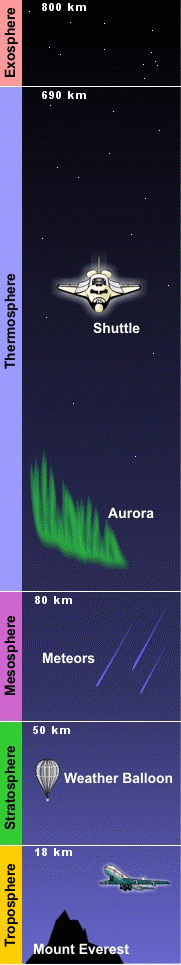

8. Draw a cross section of the atmosphere, showing its five layers and describe them.

The Earth's atmosphere consists, from the top down, of the exosphere, thermosphere, mesosphere, stratosphere, and the troposphere.

Exosphere

The exosphere is the uppermost layer of the atmosphere. On Earth, its lower boundary at the edge of the thermosphere is estimated to be 500 km to 1000 km above the Earth's surface, and its upper boundary at about 10,000 km. It is only from the exosphere that atmospheric gases, atoms, and molecules can, to any appreciable extent, escape into space. The main gases within the exosphere are the lightest gases, mainly hydrogen, with some helium, carbon dioxide, and atomic oxygen near the exobase. The exosphere is the last layer before space.

Thermosphere

The thermosphere is the layer of the earth's atmosphere directly above the mesosphere and directly below the exosphere. Within this layer, ultraviolet radiation causes ionization. It is the fourth atmospheric layer from earth.

The thermosphere begins about 80 km above the earth. At these high altitudes, the residual atmospheric gases sort into strata according to molecular mass. Thermospheric temperatures increase with altitude due to absorption of highly energetic solar radiation by the small amount of residual oxygen still present. Temperatures are highly dependent on solar activity, and can rise to 2,000°C. Radiation causes the air particles in this layer to become electrically charged, enabling radio waves to bounce off and be received beyond the horizon.

Mesosphere

The mesosphere is the layer of the Earth's atmosphere that is directly above the stratosphere and directly below the ionosphere. The mesosphere is located from about 50 km to 80-90 km altitude above Earth's surface. Within this layer, temperature decreases with increasing altitude. The main dynamical features in this region are atmospheric tides, internal atmospheric gravity waves (usually just called "gravity waves") and planetary waves. Most of these waves and tides are excited in the troposphere and lower stratosphere and propagate upward to the mesosphere. In the mesosphere, gravity-wave amplitudes can become so large that the waves become unstable and dissipate. This dissipation deposits momentum into the mesosphere and largely drives its global circulation.

Stratosphere

The stratosphere is the second layer of Earth's atmosphere, just above the troposphere, and below the mesosphere. It is stratified in temperature, with warmer layers higher up and cooler layers farther down. This is in contrast to the troposphere near the Earth's surface, which is cooler higher up and warmer farther down. The border of the troposphere and stratosphere, the tropopause, is marked by where this inversion begins, which in terms of atmospheric thermodynamics is the equilibrium level. The stratosphere is situated between about 10 km (6 miles) and 50 km (31 miles) altitude above the surface at moderate latitudes, while at the poles it starts at about 8 km (5 miles) altitude.

Troposphere

The troposphere is the lowest portion of Earth's atmosphere. It contains approximately 75% of the atmosphere's mass and almost all of its water vapor and aerosols.

The average depth of the troposphere is about 11 km in the middle latitudes. It is deeper in the tropical regions (up to 20 km) and shallower near the poles (about 7 km in summer, indistinct in winter).