Difference between revisions of "AY Honors/Birds - Advanced/Answer Key/es"

(Created page with "</noinclude> Los colibríes son atraídos por muchas plantas con flores. Se alimentan del néctar de estas plantas y son importantes polinizadores, especialmente de las flores...") |

(Created page with "También suelen consumir más de su propio peso en néctar cada día y deben visitar cientos de flores al día. En cualquier momento dado, están a solamente horas de morir de...") |

||

| Line 107: | Line 107: | ||

Los colibríes son atraídos por muchas plantas con flores. Se alimentan del néctar de estas plantas y son importantes polinizadores, especialmente de las flores de garganta profunda. | Los colibríes son atraídos por muchas plantas con flores. Se alimentan del néctar de estas plantas y son importantes polinizadores, especialmente de las flores de garganta profunda. | ||

| − | + | También suelen consumir más de su propio peso en néctar cada día y deben visitar cientos de flores al día. En cualquier momento dado, están a solamente horas de morir de hambre. | |

Hummingbirds feed in many small meals, consuming up to their own body weight in nectar and insects per day. They spend an average 10%-15% of their time feeding and 75%-80% sitting, digesting and watching. Obtaining this much food requires a lot of work. Scientists have recorded a Costa's Hummingbirds making 42 feeding flights in 6-5 hours, during which time it visited 1,311 flowers. | Hummingbirds feed in many small meals, consuming up to their own body weight in nectar and insects per day. They spend an average 10%-15% of their time feeding and 75%-80% sitting, digesting and watching. Obtaining this much food requires a lot of work. Scientists have recorded a Costa's Hummingbirds making 42 feeding flights in 6-5 hours, during which time it visited 1,311 flowers. | ||

Revision as of 17:51, 17 February 2021

| Aves - Avanzado | ||

|---|---|---|

| Asociación General

|

Destreza: 3 Año de introducción: 1949 |

|

Requisitos

|

La especialidad de Aves - Avanzado es un componente de la Maestría Naturaleza. |

|

La especialidad de Aves - Avanzado es un componente de la Maestría Zoología. |

1

Para consejos e instrucciones, véase Aves.

2

Estados Unidos

En los Estados Unidos, las aves están protegidas por una cantidad bastante grande de tratados internacionales y leyes nacionales. Estos pueden clasificarse como autoridades primarias y secundarias. Las autoridades principales son convenciones internacionales y leyes nacionales importantes que se centran principalmente en las aves migratorias y sus hábitats. Las autoridades secundarias son leyes ambientales nacionales de amplia base que proporcionan beneficios secundarios pero significativos a las aves migratorias y sus hábitats.

Leyes federales que protegen las poblaciones de aves

- La Ley de Lacey

- Arobado el 25 de mayo de 1900, prohibió la presa cazada ilegalmente en un estado para ser enviado a través de los límites del estado contrario a las leyes del estado donde se tomó.

- La Ley de Weeks-McLean

- Entró en vigencia el 4 de marzo de 1913, fue diseñada para detener la caza de mercado comercial y el envío ilegal de aves migratorias de un estado a otro. La ley proclama claramente que:

- Todos los gansos salvajes, cisnes salvajes, barnacia, patos silvestres, escolopácido, chorlito, becada, riel, palomas silvestres y todas las demás aves migratorias e insectívoras migratorias que en sus migraciones norte y sur pasan o no permanecen permanentemente durante todo el año dentro de las fronteras de cualquier estado o territorio, en lo sucesivo, se considerarán dentro de la custodia y protección del gobierno de los Estados Unidos, y no se destruirán ni se tomarán en contra de las reglamentaciones que a continuación se estipulan.

- La Ley del Tratado de Aves Migratorias de 1918

- Es la ley nacional que afirma o implementa el compromiso de los Estados Unidos con cuatro convenciones internacionales (con Canadá, Japón, México y Rusia) para la protección de un recurso compartido de aves migratorias. Cada una de las convenciones protege especies seleccionadas de aves que son comunes a ambos países (es decir, ocurren en ambos países en algún momento durante su ciclo de vida anual).

- La Ley de Especies en Peligro de Extinción

- Es también la ley nacional que confirma o implementa el compromiso de los Estados Unidos con dos tratados internacionales que contienen disposiciones importantes para la protección de las aves migratorias:

- Convención sobre el Comercio Internacional de Especies Amenazadas de Fauna y Flora Silvestres (CITES, por sus sigas inglés)

- Convenio Panamericana (Convenio sobre la Protección de la Naturaleza y la Conservación de la Vida Silvestre en el Hemisferio Occidental).

- Otros tratados internacionales

- Además de los convenios implementados por la Ley del Tratado de Aves Migratorias y la Ley de Especies en Peligro de Extinción, los Estados Unidos es parte de otros dos tratados internacionales que brindan protección especial a las aves migratorias.

- Convenio de Ramsar (la Convención Relativa a los Humedales de Importancia Internacional especialmente como Hábitat de Aves Acuáticas)

- Tratado Antártico (diseñado para proteger a las aves, los mamíferos y las plantas nativas de la Antártida)

- Otras leyes domésticas

- Otras leyes domésticas que protegen a las aves en los Estados Unidos incluyen:

- Ley de Protección del águila calva

- Ley de Prevención de Depredación de Aves Acuáticas

- Ley de Conservación de Pesca y Vida Silvestre

- Ley de Conservación de Aves Silvestres

Leyes federales que protegen los hábitats de las aves

- La Ley de Sello del Pato

- Esta ley proporciona un mecanismo para generar dinero para la adquisición y protección de importantes hábitats de aves migratorias.

- La Ley de Préstamo de Humedales

- Aprobada el 4 de octubre de 1961, autorizó un anticipo de fondos contra ingresos futuros por la venta de «sellos de pato» como medio para acelerar la adquisición del hábitat de aves acuáticas migratorias.

- La Ley de Recursos de Humedales de Emergencia

- Aprobada el 10 de noviembre de 1986, autorizó la compra de humedales a partir del dinero del Fondo de Conservación de Tierras y Aguas, eliminando la prohibición previa de tales adquisiciones.

- La Ley de Conservación de Aves Migratorias

- La Comisión de Conservación de Aves Migratorias se estableció el 18 de febrero de 1929 mediante la aprobación de la Ley de Conservación de Aves Migratorias. Fue creada y autorizada para considerar y aprobar cualquier área de tierra y/o agua recomendada por el Secretario del Interior para su compra o alquiler por el Servicio de Pesca y Vida Silvestre de los EE. UU. según la Ley, y para fijar el precio o los precios en dichas áreas que pueden ser compradas o alquiladas. Además de aprobar los precios de compra y alquiler, la Comisión considera el establecimiento de nuevos refugios para aves acuáticas.

- La Ley de Conservación de Humedales de Norteamérica

- Hace varias cosas -

- * Fomenta a las asociaciones a conservar los ecosistemas de humedales de Norteamérica para las aves acuáticas, otras aves migratorias, peces y vida silvestre.

- * Fomenta la formación de asociaciones público-privadas para desarrollar e implementar proyectos de conservación de humedales consistentes con el Plan de Manejo de Aves Acuáticas de Norteamérica (NAWMP, por sus siglas en inglés), un plan para la conservación de aves acuáticas continentales y humedales, y otros acuerdos de conservación de aves migratorias de Norteamérica.

- * Crea el Fondo de Conservación de Humedales de Norteamérica para ayudar a apoyar proyectos a través de subvenciones.

- * Establece un Consejo de Conservación de Humedales de Norteamérica (Consejo) de nueve miembros para revisar y recomendar propuestas de subvención a la Comisión de Conservación de Aves Migratorias para su financiación.

Canadá

La mayoría de las especies de aves en Canadá están protegidas por la Ley de la Convención de Aves Migratorias de 1994 (MBCA). El MBCA se aprobó en 1917 y se actualizó en 1994 y 2005 para implementar la Convención de Aves Migratorias, un tratado firmado con los Estados Unidos en 1916. Como resultado, el gobierno federal canadiense tiene la autoridad para aprobar y hacer cumplir las regulaciones [Aves migratorias Reglamento (CRC, c. 1035)] para proteger las especies de aves incluidas en la Convención. Una legislación similar en los Estados Unidos [Aves protegidas por la Ley del Tratado de Aves Migratorias] protege las especies de aves que se encuentran en ese país, aunque la lista de especies de aves protegidas por cada país puede ser diferente.

Cada provincia y territorio protege una lista de aves a través de una legislación que generalmente se denomina «Ley de vida silvestre» (o similar).

3

4

4a

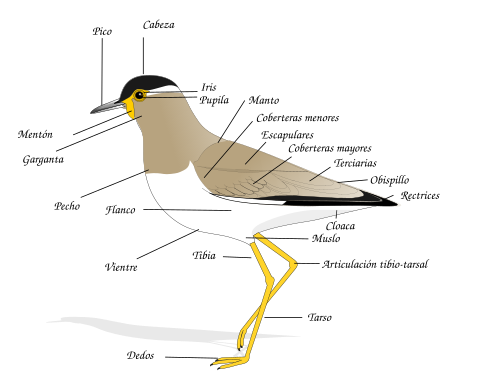

Los pies de las aves tienen muchas especializaciones. Por ejemplo, las aves que se posan tienen un mecanismo de bloqueo del tendón en sus pies que les ayuda a agarrarse a la percha cuando están dormidos. Las aves acuáticas tienen pies palmeados utilizados para una propulsión eficiente a través del agua. Las aves rapaces tienen garras afiladas en las puntas de los pies que utilizan para capturar y matar a su presa. Los pies del pingüino emperador macho tienen una forma especial para que pueda sostener un huevo encima de ellos mientras lo cubre con su cuerpo para mantenerlo caliente. El avestruz tiene sólo dos dedos en cada pie (la mayoría de las aves tienen cuatro), con la uña del más grande, la que se parece a una pezuña. El dedo exterior no tiene uña. Esta es una adaptación exclusiva de avestruces que parece ayudarle a correr.

Sus piernas también están especializadas. Las aves zancudas tienen patas largas para permitirles aventurarse en aguas más profundas en busca de peces. El avestruz tiene patas grandes y poderosas para correr (pueden alcanzar velocidades de 65 km/h, la velocidad máxima de cualquier ave). Además, sus patas no tienen plumas, lo que les permite controlar su temperatura. Cuando hay frío, pueden cubrir sus muslos con sus alas. Cuando hace calor, los descubren, lo que les permite refrescarse.

Sus picos también están altamente especializados, adaptados para comer insectos, granos, semillas de coníferas, néctar o frutas. También se adaptan a diversas formas de caza, incuyendo la alimentación por filtración, la pesca o la recolección.

4b

i

Los colibríes son atraídos por muchas plantas con flores. Se alimentan del néctar de estas plantas y son importantes polinizadores, especialmente de las flores de garganta profunda.

También suelen consumir más de su propio peso en néctar cada día y deben visitar cientos de flores al día. En cualquier momento dado, están a solamente horas de morir de hambre.

Hummingbirds feed in many small meals, consuming up to their own body weight in nectar and insects per day. They spend an average 10%-15% of their time feeding and 75%-80% sitting, digesting and watching. Obtaining this much food requires a lot of work. Scientists have recorded a Costa's Hummingbirds making 42 feeding flights in 6-5 hours, during which time it visited 1,311 flowers.

ii

Hummingbirds are such skillful fliers that they have no fear of predators. They can usually elude them with ease.

iii

Most birds move their wings up and down when they fly, but a hummingbird moves its wings front-to-back in a figure-eight pattern. This allows them to generate lift on both the forward and backward strokes, as well as endowing them with the ability to hover and fly backwards.

iv

Ruby-throated Hummingbirds migrate across the Gulf of Mexico, averaging 40 km/h (25 mph).

v

Hummingbirds are known for their ability to hover in mid-air by rapidly flapping their wings 15–80 times per second (depending on the species). Their heart rate can reach as high as 1,260 beats per minute, a rate once measured in a Blue-throated Hummingbird. However, they are capable of slowing down their metabolism at night, or any other time food is not readily available, entering a hibernation-like state known as torpor. During torpor, the heart rate and rate of breathing are both slowed dramatically (the heart rate to roughly 50–180 beats per minute), reducing their need for food.

vi

Hummingbirds' tongues are bifurcated - a fancy way of saying that like a snake, the hummingbird has a forked tongue.

5

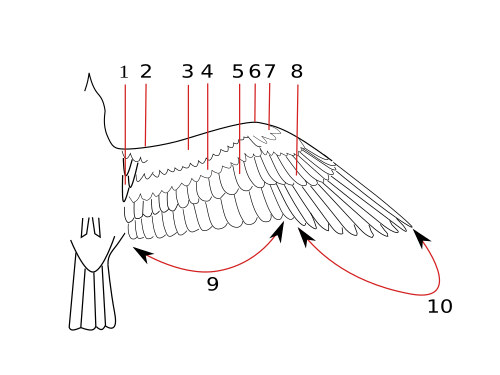

- Primaries

- Secondaries

- Coverts

- Axillars

- Alulae

- The alulea (singular is alula) are small projections on the leading edge of the wing near the carpal joint (6). They are actually one of the bird's digits, and are typically covered with three to five small feathers, with the exact number depending on the species. Like the larger flight feathers found on the wing's trailing edge, these alula feathers are asymmetrical, with the shaft running closer to leading edge.

6

Bird banding (also known as bird ringing) is an aid to studying wild birds, by attaching a small individually numbered metal or plastic ring to their legs or wings, so that various aspects of the bird's life can be studied by the ability to re-find the same individual later. This can include migration, longevity, mortality, population studies, feeding behavior, and many other aspects.

Terminology and techniques

Those who ring birds are called "bird ringers". Organized banding efforts are called "ringing schemes" and the organizations that run them, "ringing authorities". Birds are "ringed" (rather than "rung"). When a ringed bird is found, and the ring number read and reported back to the ringer or ringing authority, this is termed a "ringing recovery" or "control".

Birds are either ringed at the nest, or after being trapped in fine mist nets, Heligoland traps, drag nets, cannon nets, duck decoys or similar.

A ring of suitable size is attached, and has on it a unique number, plus a contact address. The bird is often weighed and measured, and examined for parasites (which may then be removed) before release. The rings are very light-weight, and have no adverse effect on the birds. The individual birds can then be identified when they are re-trapped, or found dead.

The finder can contact the address on the ring, give the unique number, and be told the known history of the bird's movements.

The organizing body, by collating many such reports, can then determine patterns of bird movements for large populations.

The first organized schemes for bird ringing were started (in 1909) by Arthur Landsborough Thomson in Aberdeen and Harry Witherby in England, though smaller individual marking tests had began some years earlier in Denmark and Germany.

Similar schemes

Wing tags

In some surveys, involving larger birds such as eagles, brightly-colored plastic tags are attached to birds' wing feathers. Each has a letter or letters, and the combination of color and letters uniquely identifies the bird. These can then be read in the field, through binoculars, meaning that there is no need to re-trap the birds. Because the tags are attached to feathers, they drop off when the bird moults. Imping is the practice of replacing a bird's normal feather with a brightly-colored false feather. A patagial tag is a permanent tag held onto the wing by a rivet punched through the patagium.

Radio transmitters and satellite-tracking

Where detailed information is needed on an individuals' movements, scientists can fit tiny radio transmitters to birds. For small species the transmitter is carried as a 'backpack' fitted over the wing bases, and for larger species it may be attached to a tail feather or temporary leg band. Both types usually have a tiny (10cm) flexible aerial to improve signal reception. Two field receivers (reading distance and direction) are needed to establish the bird's position using triangulation. Transmitters may be recovered by recapturing the bird or designed to drop off. The technique is useful for tracing individuals during landscape-level movements particularly in dense vegetation (such as tropical forests) and for shy or difficult-to-spot species, because birds can be located from a distance without visual confirmation. The use of satellite transmitters for bird movements is currently restricted by transmitter size - to species larger than about 400g. They may be attached to migratory birds (geese and swans are popular subjects) or other species undergoing longer-distance flights. Individuals may be tracked by satellites for immense distances, for the lifetime of the transmitter battery. As with wing tags, the transmitters may be designed to drop off when the bird moults; or they may be recovered by recapturing the bird.

Field-readable rings

A field-readable is a ring or rings, usually made from plastic and brightly colored, which may also have conspicuous markings in the form of letters and/or numbers. They are used by biologists working in the field to identify individual birds without recapture and with a minimum of disturbance to their behavior. Rings large enough to carry numbers are usually restricted to larger birds, although if necessary small extensions to the rings (leg flags) bearing the identification code allow their use on slightly smaller species. For small species (e.g. most passerines), individuals can be identified by using a combination of small rings of different colors, which are read in a specific order. Most color-marks of this type are considered temporary (the rings degrade, fade and may be lost or removed by the birds) and individuals are usually also fitted with a permanent metal ring.

Other markers

Head and neck markers are very visible, and may be used in species where the legs are not normally visible (such as ducks and geese). Nasal discs and nasal saddles can be attached to the culmen with a pin looped through the nostrils in birds with perforate nostrils. They should not be used if they obstruct breathing. They should not be used on birds that live in icy climates, as accumulation of ice on a nasal saddle can plug the nostrils. Neck collars made of expandable, non-heat-conducting plastic are very useful for larger birds such as geese.

Some results

An Arctic Tern ringed as a chick not yet able to fly, on the Farne Islands off the Northumberland coast in eastern Britain in summer 1982, reached Melbourne, Australia in October 1982, a sea journey of over 22,000 km (14,000 miles) in just three months from fledging (developing the ability to fly).

A Manx Shearwater ringed as an adult (at least 5 years old), breeding on Copeland Island, Northern Ireland, is currently (2003/2004) the oldest known wild bird in the world: ringed in July 1953, it was retrapped in July 2003, at least 55 years old. Other ringing recoveries have shown that Manx Shearwaters migrate over 10,000 km to waters off southern Brazil and Argentina in winter, so this bird has covered a minimum of 1,000,000 km on migration alone (not counting day-to-day fishing trips). Another bird nearly as old, breeding on Bardsey Island off Wales was calculated by ornithologist Chris Mead to have flown over 8 million km (5 million miles) during its life (and this bird was still alive in 2003, having outlived Chris Mead).

7

The main migration routes in North America are known as the Atlantic, Mississippi, Central, and Pacific.

8

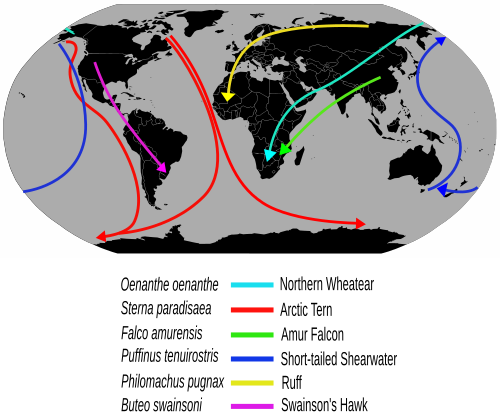

Both the routes and the terminal destinations can be found on the maps below.

- Migration Routes of eight bird species

9

Navigation is based on a variety of senses. Many birds have been shown to use a sun compass. Using the sun for direction involves the need for making compensation based on the time. Navigation has also been shown to be based on a combination of other abilities including the ability to detect magnetic fields, use visual landmarks as well as olfactory cues.

10

- a. Nombre

- b. Fecha en que fue observada

- c. Lugar en que fue observada

- d. Hábitat (campo, bosque, río, lago, etc.)

- e. Condición en que se observó (residente permanente, residente de invierno, residente de verano, migrantes, vagabundos)

Birders equip themselves with a good field guide and a checklist of birds found in the the local area they are birding. While the field guide may cover the whole continent or country and include helpful pictures and data that help you fill in the info you need for this requirement, a local checklist will narrow down the birds you can expect to actually see. You can easily find bird checklists online - look for a birding club in your area or check out /http://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/avibase.jsp?lang=EN which is based in Canada but covers the world with various degrees of completeness.

The most active times of the year for birding in temperate zones are during the spring or fall migrations when the greatest variety of birds may be seen. On these occasions, large numbers of birds travel north or south to wintering or nesting locations.

Early morning is typically the best time of the day for birding since many birds are searching for food which makes them easier to find and observe.

Birders who are keen rarity-seekers will travel long distances to locate new and rare species, intending to add these to their list of personally observed birds. These lists often take the form of a life list, national list, state list, county list, or year list.

Seawatching is a type of birdwatching where observers based at a coastal watch point, such as a headland, watch birds flying over the sea. This is one form of pelagic birding, by which pelagic bird species are viewed. Another way birders view pelagic species is from seagoing vessels.

Many birders take part in censuses of bird populations and migratory patterns which are sometimes specific to individual species. These birders may also count all birds in a given area, as in the Christmas Bird Count. This citizen science can assist in identifying environmental threats to the well-being of birds or, conversely, in assessing outcomes of environmental management initiatives intended to ensure the survival of at-risk species or encourage the breeding of species for aesthetic or ecological reasons. This more scientific side of the hobby is an aspect of ornithology, coordinated in the UK by the British Trust for Ornithology.

Increasing seasonal bird populations can be a good indication of biodiversity or the quality of different habitats. Some species are persecuted as vermin, often illegally, as with the case of the Hen Harrier in Britain.

11

- a. Un día (con un mínimo de seis horas en el campo)

- b. Una semana

- c. Su vida (todas las aves observadas por usted desde que empezó la observación de aves hasta la fecha actual)

As you observe birds and record the data called for in requirement 10, you can go through the data at a later time to collect this information. You can also log your observations online at places such as http://www.birdingcentral.com/ Using the Internet for logging your data will connect you to an international community of bird watchers. You will be better able to know when and where to look for various species of birds, and you may make some lifelong friends in the process.

12

Birding often involves a significant auditory component, as many bird species are more readily detected and identified by ear than by eye. Listen to the bird calls found in the Field Guide. Then listen for them in the wild. You can also check out Birding by Ear guides.

13

You will learn where the best places to see birds are as you go out birding yourself. If possible, take a group to one of those places. You can combine this trip with one of another purpose (such as a hike).

Bible stories that feature a bird as a significant part include, Noah sending out the dove, and Elijah being fed by ravens. In the Sermon on the Mount Jesus asks us to consider the birds of the air (they neither sow nor reap). The baptism of Jesus and Pentecost also feature doves.

References

- Categoría: Tiene imagen de insignia

- Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Honors/es

- Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/es

- Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Skill Level 3/es

- Categoría: Libro de respuestas de especialidades JA/Especialidades introducidas en 1949

- Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/General Conference/es

- Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/es

- Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Primary/es

- Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Stage 0/es

- Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Naturalist Master Award/Fauna/es

- Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Zoology Master Award/Fauna/es

- AY Honors/Prerequisite/Birds/es

- AY Honors/See Also/Birds/es

- Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book