|

|

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

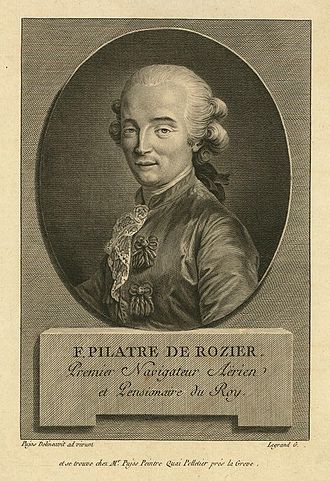

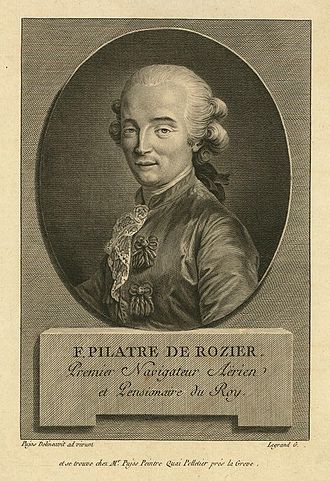

| − | [[Image:Jacques Étienne Montgolfier.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Jacques Étienne Montgolfier]] | + | [[Image:Pilatre de Rozier.jpg|thumb|right|Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier.]] |

| | | | |

| − | {{For|the indie pop band|The Montgolfier Brothers}}

| + | '''Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier''' ([[30 March]] [[1754]] – [[15 June]] [[1785]]) was a [[France|French]] [[chemistry]] and [[physics]] teacher, and one of the first pioneers of [[aviation]]. His balloon crashed near [[Wimereux]] in the [[Pas-de-Calais]] during an attempt to fly across the [[English Channel]], and he and his companion, Pierre Romain, became the first known victims of an [[air crash]]. |

| − | The brothers, '''Joseph Michel Montgolfier''' ([[26 August]] [[1740]] – [[26 June]] [[1810]]) and '''Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier''' ([[6 January]] [[1745]] – [[2 August]] [[1799]]) were the inventors of the '''''montgolfière''''', ''globe airostatique'' or European [[hot air balloon]]. The brothers succeeded in launching the first manned ascent to carry a young physician and an audacious army officer into the sky. They were later enobled with their father and brothers and sisters as '''de Montgolfier'''.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ==Early years==

| + | He was born in [[Metz]], the fourth son of Magdeleine Wilmard and Mathurin Pilastre, known as "du Rosier", a former soldier who became an innkeeper. His interests in the chemistry of drugs had been awakened in the military hospital of [[Metz]], an important garrison town on the border of France. He made his way to [[Paris]] at the age of 18, then taught physics and chemistry at the Academy in [[Reims]], which brought him to the attention of [[Louis XVIII of France|Monsieur, the comte d'Artois]], brother of King [[Louis XVI of France|Louis XVI]]. He returned to Paris, where he was put in charge of Monsieur's ''cabinet'' of [[natural history]] and made him a ''valet de chambre'' to Monsieur's wife, Madame, which brought him his ennobled name, Pilâtre de Rozier. He opened his own museum in the [[Le Marais|Marais]] quarter of Paris on [[11 December]] [[1781]], where he undertook experiments in physics and provided demonstrations to nobles. He researched the new field of [[gas]]es and invented a [[respirator]]. |

| − | The brothers were borne into a family of [[paper]] manufacturers in [[Annonay]], in [[Ardèche]], France to Pierre Montgolfier ([[Tence]], [[21 February]] [[1700]] – [[Vidalon]], [[1 June]] [[1793]]), enobled as Pierre de Montgolfier in December [[1783]] by King [[Louis XVI of France]] and wife (married at [[Annonay]], [[14 July]] [[1727]]) Anne Duret ([[Annonay]], [[14 February]] [[1701]] – [[Vidalon]], [[11 March]] [[1760]]), the parents of sixteen children. He was the son of Hoe Montgolfier ([[Beaujeau]], [[10 March]] [[1673]] – [[Davezieux]], [[6 February]] [[1743]]), [[papermaker]], and wife (married at [[Tence]], [[14 January]] [[1693]]) Marguerite Chelles ([[Job]], bef. [[1676]] – [[Davezieux]], [[17 May]] [[1736]]). She was the daughter of Charles Duret (d. [[Annonay]], [[21 May]] [[1738]]) and wife (married on [[30 September]] [[1691]]) Isabeau Bruyere.<ref>http://www.wargs.com/noble/anna.html</ref> Pierre established his eldest son Raymond Montgolfier, later Raymond de Montgolfier ([[Vidalon]], [[28 July]] [[1730]] – [[Lyon]], [[31 July]] [[1792]] and married on [[5 March]] [[1761]] to Claudine Devant who died at [[Annonay]], [[1800]], by whom he had issue) as his successor. As a result, the younger sons were initially sent away to school to learn other professions.

| |

| | | | |

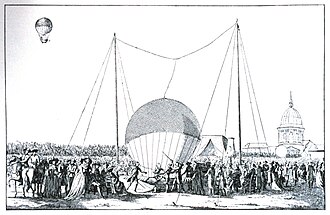

| − | [[Image:Josephmontgolfier.jpg|thumb|200px|left|Joseph Michel Montgolfier]] | + | [[Image:Ballon de Rozier.jpg|thumb|left|The first tethered balloon ascent on [[15 October]] [[1783]] by Rozier.]] |

| | | | |

| − | Joseph (12th child) possessed a typical inventor's temperament -- a maverick and dreamer but impractical in terms of business and personal affairs. Étienne had a much more even and businesslike temperament than Joseph. As the 15th child he was sent to Paris to train as an architect. However, after the sudden and unexpected death of Raymond in 1772, he was recalled to Annonay to run the family business. In the subsequent 10 years, Étienne applied his talent for technical innovation to the family business; papermaking was a high-tech industry in the 18th century. He succeeded in incorporating the latest Dutch innovations of the day into the family mills. His work led to recognition by the government of France as well as the awarding of a government grant to establish the Montgolfier factory as a model for other French papermakers, but also to the family wealth.

| + | In June [[1783]], he witnessed the first [[balloon]] flight of the [[Montgolfier brothers]]. On [[19 September]], he assisted with the untethered flight of a sheep, a cockerel and a duck from the front courtyard of the [[Palace of Versailles]]. After a variety of tests in October, he made the first manned '''free''' flight in history on [[21 November]] [[1783]], accompanied by the ambitious [[Marquis d'Arlandes]]. During the 25-minute flight using a Montgolfier [[hot air balloon]], they traveled 12 [[kilometre]]s from the [[Château de la Muette]] to the [[Butte-aux-Cailles]], then in the [[suburbs|outskirts]] of Paris, attaining an [[altitude]] of 3,000 feet. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Initial experiments==

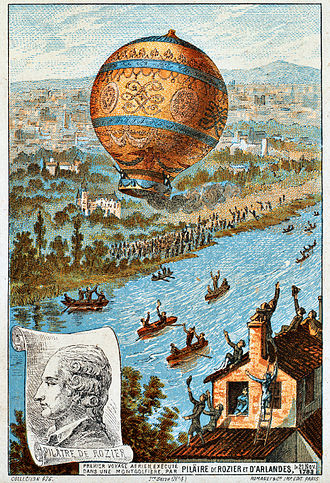

| + | [[Image:Early flight 02562u (4).jpg|thumb|The first untethered balloon flight, by Rozier and the [[Marquis d'Arlandes]] on [[21 November]] [[1783]].]] |

| − | Of the two brothers, it was Joseph who first contemplated building "''machines''". Gillispie puts it as early as 1777 when Joseph observed laundry drying over a fire incidentally form pockets that billowed upwards.<ref>C.C. Gillispie, The Montgolfier brothers and the invention of aviation 1783-1784, p. 15.</ref> Joseph made his first definitive experiments in November of 1782 while living in [[Avignon]]. He reported, some years later, that he was watching a fire one evening while contemplating one of the great military issues of the day -- an assault on the fortress of [[Gibraltar]], which had proved impregnable by both sea and land.<ref>C.C. Gillispie, p. 16.</ref> Joseph mused on the possibility of an air assault using troops lifted by the same force that was lifting the embers from the fire. He believed that contained within the smoke was a special gas, called 'Montgolfier Gas', with a special property he called 'levity'.

| |

| | | | |

| − | As a result of these musings, Joseph set about building a box-like chamber 1x1x1,3m (3 [[foot|ft]] by 3 ft by 4 ft) out of very thin wood and covering the sides and top with lightweight [[taffeta]] cloth. Under the bottom of the box he crumpled and lit some paper. The contraption quickly lifted off its stand and collided with the ceiling. Joseph then recruited his brother to balloon building by writing the prophetic words: "Get in a supply of [[taffeta]] and of cordage, quickly, and you will see one of the most astonishing sights in the world."<ref>C.C. Gillispie, p. 17.</ref>

| + | Along with [[Joseph Montgolfier]], he was one of six passengers on a second flight on [[19 January]] [[1784]], with a huge Montgolfier balloon ''Le Flesselles'' launched from [[Lyon]]. Four French nobles paid for the trip, including a prince. Several difficulties had to be overcome. The wallpaper became wet because of extreme weather conditions. The top of the balloon was made of sheep- or [[buckskin]]. The air was heated by wood in an iron stove: to start, the straw was set on fire with [[brandy]]. (In other tests charcoal or potatoes were used). The balloon had a volume of approximately 23,000 [[m³]], over 10 times that of the first flight, but only flew a short distance. The spectators kneeled down when the balloon came down too quickly. That evening the aeronauts were celebrated after listening to [[Gluck]]'s opera, [[Iphigénie en Tauride]]. |

| | | | |

| − | The two brothers then set about building a contraption 3 times larger in scale (27 times larger in volume). The lifting force was so great that they lost control of their craft on its very first test flight on [[14 December]] [[1782]]. The device floated nearly 2 kilometres (about 1.2 mi). It was destroyed after landing by the "indiscretion" of passersby.<ref>C.C. Gillispie, p. 21.</ref>

| + | Rosier took part in a further flight on [[23 June]] [[1784]], in a modified version of the Montgolfier's first balloon christened ''La Marie-Antoinette'' after the Queen, which took off in front of the King of France and King [[Gustav III of Sweden]]. Together with [[Joseph Proust]], the balloon flew north at an altitude of approximately 3,000 metres, above the clouds. They travelled 52 km in 45 minutes before cold and turbulence forced them to descend past [[Luzarches]], between [[Coye]] et [[Orry-la-Ville]], near the [[Chantilly forest]]. They set records for speed, altitude and distance travelled. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Public demonstrations==

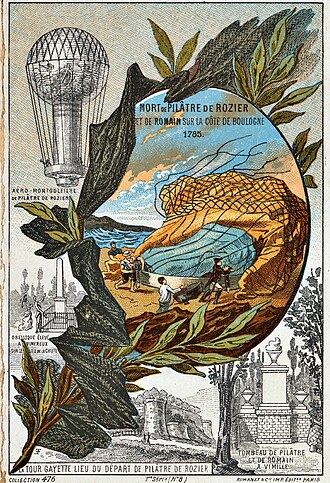

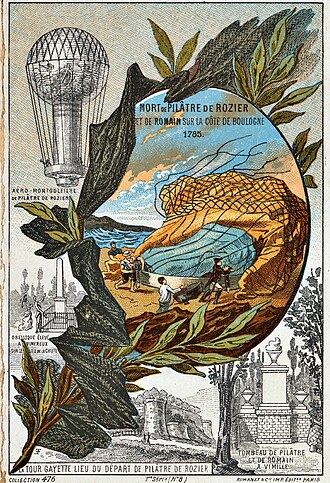

| + | [[Image:Aviation fatality - Pilatre de Rozier and Romain.jpg|thumb|left|Fatal accident at [[Wimereux]], [[15 June]] [[1785]].]] |

| − | [[Image:Early flight 02562u (2).jpg|thumb|left|150px|First public demonstration in [[Annonay]], [[1783-06-04]].]] | |

| | | | |

| − | The brothers decided to make a public demonstration of a balloon in order to establish their claim to its invention. They constructed a globe-shaped balloon of sackcloth with three thin layers of paper inside. The envelope could contain nearly 790 m³ (28,000 cubic feet) of air and weighed 225 kg (500 lb). It was constructed of four pieces (the dome and three lateral bands), and held together by 1,800 buttons. A reinforcing "fish net" of cord covered the outside of the envelope.

| + | ==Final flight== |

| | + | De Rozier's next plan was an attempt to cross the [[English Channel]] from France to England. A Montgolfier balloon would not be up to the task, requiring large stocks of fuel for the hot air, so his balloon was a combination [[hydrogen]] and [[hot air balloon]]. It was prepared in the autumn of 1784, but the attempt was not launched until after another Frenchman, [[Jean-Pierre Blanchard]], and American companion, Dr [[John Jeffries]], flew across the [[English Channel]] in a hydrogen gas balloon on [[7 January]] [[1785]], from England to France. |

| | | | |

| − | On [[4 June]] [[1783]], they flew this craft as their first public demonstration at Annonay in front of a group of dignitaries from the ''Etats particulars''. Its flight covered 2 km (1.2 mi), lasted 10 minutes, and had an estimated altitude of 1.600 - 2.000m (5,200 - 6,600 ft). Word of their success quickly reached Paris. Etienne went to the capital to make further demonstrations and to solidify the brothers' claim to the invention of flight. Joseph, given his unkempt appearance and shyness, remained with the family. Etienne was ''the epithome of sober virtues ... modest in clothes and manner...''<ref>S. Schama (1989) Citizens. A Chronicle of the French Revolution, p. 125.</ref> He was dressed stylishly in black.

| + | [[Image:Early flight 02562u (8).jpg|thumb|Deaths of Rozier and Romain.]] |

| | | | |

| − | [[Image:Montgolfier Balloon.JPG|thumb|right|150px|A model of the Montgolfier brothers balloon at the [[London Science Museum]]]] | + | Despite several attempts, De Rozier and his companion, Pierre Romain, were not able to set off from [[Boulogne-sur-Mer]] until [[15 June]] [[1785]]. After making some progress, a change of wind direction pushed them back to land some 5 km from their starting point. The balloon suddenly deflated (without the envelope catching fire) and crashed near [[Wimereux]] in the [[Pas-de-Calais]]. Both occupants were killed, and horrified reports were grimly detailed. The young hero swam in his own blood. Eight days later his fiancée committed suicide. A commemorative obelisk was later erected at the site of the crash. |

| | | | |

| − | In collaboration with the successful manufacturer, [[Jean-Baptiste Réveillon]], Etienne constructed a 37,500 cubic foot envelope of taffeta coated with a varnish of [[alum]]. The balloon was sky blue and with golden flourishes, signs of the [[zodiac]], suns. The design was the influence of Réveillon, a [[wallpaper]] maker. The next test was on the 11th of September from the parc ''la [[Folie Titon]]'', close to the house of Réveillon. There was some concern about the effects of flight into the upper atmosphere on living creatures. The king proposed to launch two criminals, but it is most likely that the inventors decided to send animals aloft first.

| + | The modern hybrid gas and hot air balloon is named the [[Rozière balloon]] after his pioneering design. |

| − | | |

| − | On [[19 September]] [[1783]] the ''Aerostat Réveillon'' was flown with the first living beings in a basket attached to the balloon: a sheep, called Montauciel (Climb-to-the-sky), a duck and a rooster. This demonstration was performed before a huge crowd at the royal palace in [[Versailles]], before King [[Louis XVI of France]], Queen [[Marie Antoinette]].<ref>C.C. Gillispie, p. 92-3.</ref> The flight lasted approximately eight minutes, covered two miles, and obtained an altitude of about 1500 feet. The flight would have been longer but the craft was unstable. It tipped wildly just after launch which allowed a considerable amount of hot air to spill from the mouth. The animals survived the trip unharmed. ''...the sheep was discovered nibbling imperturbably on straw while the cock and the duck cowered in a corner.''<ref>S. Schama (1989), p. 123.</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Human flight==

| |

| − | [[Image:Montgolfierer 1783.jpg|thumb|left|250px|First attempt from the parc ''La Folie Titon'' on October, 19th 1783.]]

| |

| − | With the successful demonstration at Versailles, and again in collaboration with Réveillon, Etienne started construction of a 60,000 cubic foot balloon for the purpose of making flights with humans. The craft was 75 feet tall and 46 feet in diameter. The balloon was tested in tethered flights on [[15 October]] by [[Pilâtre de Rozier]], a twenty-six-year-old physician, who offered his services. On the [[17 October]] the experiment was repeated before a group of scientists and [[19 October]] Rozier and André Giroud de Villette, a wallpaper manufacturer from Madrid, reached 324 foot within 15 seconds along retaining ropes.

| |

| − | | |

| − | On [[21 November]] the first free flight by humans was made by Pilâtre, together with an army officer, the [[marquis d'Arlandes]]. The flight began near the [[Bois de Boulogne]] in the parc of the [[Château de la Muette]] in the western outskirts of Paris. They flew aloft about 3,000 feet above [[Paris]] for a distance of nine kilometres. After 25 minutes the machine landed between the windmills, outside the city ramparts, on the [[Butte-aux-Cailles]]. Enough fuel remained on board at the end of the flight to have allowed the balloon to fly four to five times as far. However, burning embers from the fire were scorching the balloon fabric and had to be daubed out with sponges. As it appeared it could destroy the balloon, Pilâtre took off his coat to stop the fire.

| |

| − | | |

| − | The ascensions made a sensation. Numerous engravings commemorated the events. Chairs were designed with balloon backs, and mantel clocks were produced in enamel and gilt-bronze replicas set with a dial in the balloon. One could buy crockery decorated with naive pictures of balloons.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Following launches==

| |

| − | In 1766, the British scientist [[Henry Cavendish]] had discovered hydrogen, by adding sulphuric acid to iron, tin, or zinc shavings. The development of [[gas balloon]]s proceeded almost in parallel with the work of the Montgolfiers. This work was led by [[Jacques Alexandre César Charles|M. Charles]]. On the 27th of August a [[hydrogen]] balloon was launched from the [[Champ de Mars]] in Paris. Six thousand people paid for a seat. A downpour of rain ended the show. On December, the 1st, prof. Charles went up into the sky twice.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Work on each type of balloon was spurred on by the knowledge that there was a competing group and alternative technology. For a variety of reasons, including the fact that the French government chose to put a proponent of hydrogen in charge of balloon development, [[hot air balloon]]s were superseded by [[hydrogen]] balloons. Hydrogen balloons became the predominant technology for the next 180 years.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Hydrogen balloons were used for all major ballooning accomplishments such as the crossing of the English Channel on [[7 January]] [[1785]], by the tireless aviators [[Jean-Pierre Blanchard]] and Dr. [[John Jeffries]], from Boston.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Competing claims==

| |

| − | Some claim that the hot air balloon was actually invented some 74 years earlier by the [[Portugal|Portuguese]] priest [[Bartolomeu de Gusmão]].<ref> [http://www.instituto-camoes.pt/cvc/ciencia/p2.html Reis, Fernando. ''Bartolomeu de Gusmão''.Ciência em Portugal. Centro Virtual Camões] in Portuguese</ref> A description of his invention was published in 1709, in Vienna, and another one that was lost was found in the Vatican (circa 1917).<ref> [http://purl.pt/706/3/ Gusmao, Bartolomeu de. ''Reproduction fac-similé d'un dessin à la plume de sa description et de la pétition addressée au Jean V. (de Portugal) en langue latine et en écriture contemporaine (1709) retrouvés récemment dans les archives du Vatican du célèbre aéronef de Bartholomeu Lourenco de Gusmão "l'homme volant" portugais, né au Brésil (1685-1724) précurseur des navigateurs aériens et premier inventeur des aérostats.'' 1917 (Lausanne : Impr. Réunies S. A..)] in French and Latin</ref>

| |

| − | However, this claim is not generally recognized by aviation historians outside the Portuguese speaking community, in particular the [[F%C3%A9d%C3%A9ration_A%C3%A9ronautique_Internationale|FAI]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Revival of the hot air balloon==

| |

| − | Although balloons employing heated air for lift were used from time to time, the modern revival of the hot air balloon began on 22 October 1960 in Bruning, Nebraska on when [[Ed Yost]] improved the safety of the classic Montgolfier design by using a plastic envelope and a kerosene fueled heater.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Today, hot air balloons that use [[propane]] fuel and [[ripstop nylon]] envelopes are by far the predominant method for obtaining buoyant flight.

| |

| | | | |

| | ==References== | | ==References== |

| − | <references/>

| + | * [[Barthélemy Faujas de Saint-Fond]] (1783, 1784) Description des expériences de la machine aérostatique de MM. Montgolfier, &c. |

| | + | * [[Simon Schama]] (1987) Citizins, p. 123-31. |

| | | | |

| | ==External links== | | ==External links== |

| | + | * http://bellestar.org/BalloonHistory.aspx |

| | + | * http://clg-pilatre-de-rozier.scola.ac-paris.fr/PDRBio.htm |

| | | | |

| − | *[http://www.chm.bris.ac.uk/webprojects2003/hetherington/final/montgolfier_bros.html "Lighter than air: the Montgolfier brothers"]

| + | {{DEFAULTSORT:Pilatre de Rozier, Jean-Francois}} |

| − | *[http://www.start-flying.com/Montgolfier.htm "Balloons and the Montgolfier brothers"]

| + | [[Category:1757 births]] |

| − | * http://www.twinring.jp/english/balloon/what_balloon/

| + | [[Category:1785 deaths]] |

| − | | |

| − | {{DEFAULTSORT:Montgolfier Brothers}}

| |

| − | | |

| | [[Category:French balloonists]] | | [[Category:French balloonists]] |

| − | [[Category:French people]] | + | [[Category:Accidental deaths]] |

| − | [[Category:Sibling duos]]

| + | [[Category:People from Metz]] |

| − | [[Category:People of the Industrial Revolution]] | + | [[Category:Aviators killed in aircraft crashes in France]] |

| − | [[Category:Aviation pioneers]]

| |

| − | [[Category:Papermakers]]

| |

| − | [[Category:1740 births]] | |

| − | [[Category:1745 births]]

| |

| − | [[Category:1799 deaths]]

| |

| − | [[Category:1810 deaths]]

| |

| − | | |

| − | Emily rocks

| |

| | | | |

| − | [[cs:Joseph-Michel Montgolfier]] | + | [[da:Pilâtre de Rozier]] |

| − | [[de:Montgolfier]] | + | [[de:Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier]] |

| − | [[es:Hermanos Montgolfier]] | + | [[es:Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier]] |

| − | [[fr:Frères Montgolfier]] | + | [[fr:Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier]] |

| − | [[hr:Braća Montgolfier]] | + | [[hr:Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier]] |

| − | [[io:Montgolfier fratuli]] | + | [[id:Pilâtre de Rozier]] |

| − | [[it:Fratelli Montgolfier]] | + | [[it:Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier]] |

| − | [[he:האחים מונגולפייה]]

| + | [[nl:Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier]] |

| − | [[nl:Gebroeders Montgolfier]] | + | [[pl:Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier]] |

| − | [[ja:モンゴルフィエ兄弟]]

| + | [[pt:Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier]] |

| − | [[no:Brødrene Montgolfier]]

| + | [[ru:Розье, Пилатр де]] |

| − | [[pl:Bracia Montgolfier]] | + | [[sv:François Pilâtre de Rozier]] |

| − | [[pt:Etiene e Joseph Montgolfier]] | |

| − | [[ro:Fraţii Montgolfier]]

| |

| − | [[ru:Монгольфье]] | |

| − | [[sr:Браћа Монголфје]]

| |

| − | [[fi:Montgolfierin veljekset]]

| |

| − | [[sv:Montgolfier]] | |

| − | [[tr:Montgolfier Kardeşler]]

| |

| − | [[uk:Брати Монгольф'є]]

| |

| − | [[zh:孟格菲兄弟]]

| |

Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier.

Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier (30 March 1754 – 15 June 1785) was a French chemistry and physics teacher, and one of the first pioneers of aviation. His balloon crashed near Wimereux in the Pas-de-Calais during an attempt to fly across the English Channel, and he and his companion, Pierre Romain, became the first known victims of an air crash.

He was born in Metz, the fourth son of Magdeleine Wilmard and Mathurin Pilastre, known as "du Rosier", a former soldier who became an innkeeper. His interests in the chemistry of drugs had been awakened in the military hospital of Metz, an important garrison town on the border of France. He made his way to Paris at the age of 18, then taught physics and chemistry at the Academy in Reims, which brought him to the attention of Monsieur, the comte d'Artois, brother of King Louis XVI. He returned to Paris, where he was put in charge of Monsieur's cabinet of natural history and made him a valet de chambre to Monsieur's wife, Madame, which brought him his ennobled name, Pilâtre de Rozier. He opened his own museum in the Marais quarter of Paris on 11 December 1781, where he undertook experiments in physics and provided demonstrations to nobles. He researched the new field of gases and invented a respirator.

In June 1783, he witnessed the first balloon flight of the Montgolfier brothers. On 19 September, he assisted with the untethered flight of a sheep, a cockerel and a duck from the front courtyard of the Palace of Versailles. After a variety of tests in October, he made the first manned free flight in history on 21 November 1783, accompanied by the ambitious Marquis d'Arlandes. During the 25-minute flight using a Montgolfier hot air balloon, they traveled 12 kilometres from the Château de la Muette to the Butte-aux-Cailles, then in the outskirts of Paris, attaining an altitude of 3,000 feet.

Along with Joseph Montgolfier, he was one of six passengers on a second flight on 19 January 1784, with a huge Montgolfier balloon Le Flesselles launched from Lyon. Four French nobles paid for the trip, including a prince. Several difficulties had to be overcome. The wallpaper became wet because of extreme weather conditions. The top of the balloon was made of sheep- or buckskin. The air was heated by wood in an iron stove: to start, the straw was set on fire with brandy. (In other tests charcoal or potatoes were used). The balloon had a volume of approximately 23,000 m³, over 10 times that of the first flight, but only flew a short distance. The spectators kneeled down when the balloon came down too quickly. That evening the aeronauts were celebrated after listening to Gluck's opera, Iphigénie en Tauride.

Rosier took part in a further flight on 23 June 1784, in a modified version of the Montgolfier's first balloon christened La Marie-Antoinette after the Queen, which took off in front of the King of France and King Gustav III of Sweden. Together with Joseph Proust, the balloon flew north at an altitude of approximately 3,000 metres, above the clouds. They travelled 52 km in 45 minutes before cold and turbulence forced them to descend past Luzarches, between Coye et Orry-la-Ville, near the Chantilly forest. They set records for speed, altitude and distance travelled.

Final flight

De Rozier's next plan was an attempt to cross the English Channel from France to England. A Montgolfier balloon would not be up to the task, requiring large stocks of fuel for the hot air, so his balloon was a combination hydrogen and hot air balloon. It was prepared in the autumn of 1784, but the attempt was not launched until after another Frenchman, Jean-Pierre Blanchard, and American companion, Dr John Jeffries, flew across the English Channel in a hydrogen gas balloon on 7 January 1785, from England to France.

Deaths of Rozier and Romain.

Despite several attempts, De Rozier and his companion, Pierre Romain, were not able to set off from Boulogne-sur-Mer until 15 June 1785. After making some progress, a change of wind direction pushed them back to land some 5 km from their starting point. The balloon suddenly deflated (without the envelope catching fire) and crashed near Wimereux in the Pas-de-Calais. Both occupants were killed, and horrified reports were grimly detailed. The young hero swam in his own blood. Eight days later his fiancée committed suicide. A commemorative obelisk was later erected at the site of the crash.

The modern hybrid gas and hot air balloon is named the Rozière balloon after his pioneering design.

References

External links

da:Pilâtre de Rozier

de:Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier

es:Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier

fr:Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier

hr:Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier

id:Pilâtre de Rozier

it:Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier

nl:Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier

pl:Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier

pt:Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier

ru:Розье, Пилатр де

sv:François Pilâtre de Rozier