Difference between revisions of "AY Honors/Sharks/Answer Key"

JadeDragon (talk | contribs) |

JadeDragon (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

{{:Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Species Account/Sphyrna mokarran}} | {{:Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Species Account/Sphyrna mokarran}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{:Adventist_Youth_Honors_Answer_Book/Species_Account/Rhincodon_typus}} | ||

{{:Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Species Account/Etmopterus perryi}} | {{:Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Species Account/Etmopterus perryi}} | ||

Revision as of 20:33, 6 May 2014

Template:AY patch unavailable Template:Honor header Template:AY Master

1. On what day of Creation Week were sharks created?

Sharks were created on the fifth day:

Then God said, “Let the waters swarm with fish and other life. Let the skies be filled with birds of every kind.” So God created great sea creatures and every living thing that scurries and swarms in the water, and every sort of bird—each producing offspring of the same kind. And God saw that it was good. Then God blessed them, saying, “Be fruitful and multiply. Let the fish fill the seas, and let the birds multiply on the earth.” And evening passed and morning came, marking the fifth day.

2. What is the study of sharks called?

The study of the subclass of fish known as cartilaginous (skeleton made from cartilage like in your nose, with no bones) including sharks, rays, and skates is called Elasmobranchology. These fish are collectively called the elasmobranchii.

3. Identify from pictures or personal observation 10 species of sharks.

Sharks are a group of fish characterized by a cartilaginous skeleton (cartilage, not bone), five to seven gill slits on the sides of the head that they breath through, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Sharks have a covering of dermal denticles that protects their skin from damage and parasites in addition to improving their fluid dynamics. They have several sets of replaceable teeth. Modern sharks are classified within the clade Selachimorpha (or Selachii) and are the sister group to the rays.

There are about 470 species of sharks which range in size from the small dwarf lanternshark (Etmopterus perryi), a deep sea species of only 17 centimetres (6.7 in) in length, to the whale shark (Rhincodon typus), the largest fish in the world, which reaches approximately 12 metres (39 ft). Sharks are found in all seas and are common to depths of 2,000 metres (6,600 ft). They generally do not live in freshwater although there are a few known exceptions, such as the bull shark and the river shark, which can survive in both seawater and freshwater. We present more than ten for your review.

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Species Account/Sphyrna mokarran

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Species Account/Rhincodon typus

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Species Account/Etmopterus perryi

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Species Account/Negaprion brevirostris

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Species Account/Isurus oxyrinchus

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Species Account/Carcharhinus limbatus

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Species Account/Carcharhinus brachyurus

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Species Account/Carcharhinus longimanus

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Species Account/Hemiscyllium Halmahera

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Species Account/Carcharhinus leucas

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Species Account/Carcharodon carcharias

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Species Account/Prionace glauca

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Species Account/Galeocerdo cuvier

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Species Account/Somniosus microcephalus

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Species Account/Megachasma pelagios

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Species Account/Brachaelurus waddi

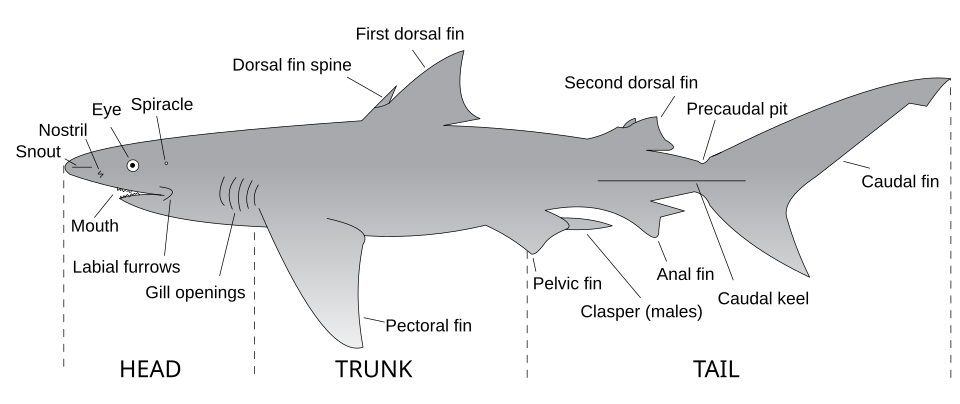

4. Draw a shark and identify the following shark parts:

- a. 1st Dorsal fin

- top of shark, forward

- b. 2nd Dorsal fin

- top of shark, rear

- c. Pectoral fin

- sides of shark, like arms

- d. Pelvic fin

- bottom of shark, toward rear but ahead of anal fin

- e. Anal fin

- bottom of shark, toward rear

- f. Caudal fin

- the fins at the tail end of the shark

- g. Gill openings

- used to process water for oxygen

- h. Spine

- top of shark, bones like on humans

- i. Eye

- on head

- j. Snout

- the big nose, front end

- k. Nostril

- the nose opening

- l. Mouth

- where you find the teeth, not a good place for your arm

5. Explain the shark sensory system: Smell, Sight, Taste, Hearing, Touch, Electroreception

Smell, sight, taste, hearing, touch, and electroreception are the six sensory systems sharks are equipped with allowing them to successfully exploit the environment they live in by locating prey, avoiding danger and finding a mate.

Smell

Sharks possess a pair of nostrils (also referred to as nares), just under the edge of their snout. The nares are completely separate from the mouth and throat and do not aid in respiration. Instead they are used purely for olfaction. Each nare is divided into two channels by a nasal flap. The water enters one channel (incurrent aperture) and passes over an area called the olfactory lamellae which contain neuro-sensory cells. These then send chemosensory information via the olfactory bulb to the large olfactory lobe in the shark's forebrain. The olfactory lamellae are a series of folds on the surface of the olfactory sac; these folds increase the surface area and provide the shark with a greater opportunity of detecting smells. After passing through the olfactory sac the water is then channeled out through the recurrent aperture.

If the shark detects a smell which it wants to investigate (odor from prey or pheromones from a potential mate), it will swim in the direction of the scent moving its head back and forth (similar to its natural swimming motion), this motion will allow it to detect the direction of the smell by following the most concentrated signal. These movements can become exaggerated into larger “S” shapes if the shark loses the signal or if the signal is too wide to use for accurate navigation.

Sight

In the majority of shark species, the eyes are well developed, complex structures containing rod (highly sensitive to light intensity) and in some species cone cells (may allow sharks to see in color). They can control the amount of light entering the eye by dilating or contracting their pupils. Focusing is controlled by the rectus muscles which pull the lens closer to or further away from the retina. When used in conjunction with the oblique muscles, movement of the entire eye is achieved.

Most sharks have excellent vision in dim light conditions; this is due to the retina containing millions of rod cells together with a structure called the tapetum lucidum. This is a layer found behind the retina which reflects light back onto the retina, amplifying the image. Pigmented cells cover the tapetum reducing reflections and protecting the retina in bright light.

Sharks have an upper and lower eyelid but these usually do not meet and therefore do not provide a full cover for the eye. Some sharks, such as the tiger shark, have a “third eyelid” known as the nictitating membrane. This rolls up from the base of the eye to completely cover the eyeball. The use of this nicitating membrane is demonstrated regularly in shark documentaries, and most notably when the shark is attacking its prey. Species like the white shark which do not have the nicitating membrane often employ a different strategy to safeguard the eye; they roll the eye into the back of the socket exposing a hardened pad at the rear of the eyeball. The existence of such strategies designed to protect the eye, highlight the importance of sight as a sensory function to the shark.

Some sharks, such as the blue shark, have a light sensitive “third eye”. Indicated by a lighter colored spot called the pineal window on the top of the sharks head directly above the pineal gland. Athough speculative, it is suggested that the shark may use this to aid navigation.

Taste

As a shark bites into an object (prey or otherwise), chemicals are released and attach themselves to gustatory sensory cells present in the shark's mouth and throat. These gustatory cells then send messages to structures (the thalamus and the hypothalamus) located in the shark's forebrain. The shark will then either accept or reject the object it has bitten.

Hearing

The shark ear is located in the frontal skull (chrondocranium) and is completely internal with only a tiny opening on the shark's head - not the spiracle which is involved in respiration. The ear detects sound with frequencies ranging from <20 to about 800 Hertz (humans detect sound between 20 and 20,000 Hertz). Most sharks show an attraction to infrasound (<20Hz). This is most likely due to the low frequency sounds emitted by struggling prey. The shark ear is also used for balance and orientation (by utilizing the fluid-filled semi-circular canals, with the movement of the fluid activating sensory hair cells) and pressure detection (by direct activation of the hair cells within the canals allowing sensory signals to be relayed to the brain via the auditory nerve).

Touch

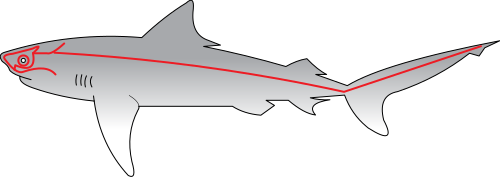

A shark can feel a certain amount of direct contact due to free nerve endings embedded in the skin, mouth, jaws and even teeth. They can also sense things internally due to the presence of proprioceptors (microscopic sensory cells) found throughout the muscles, joints, digestive system and blood vessels. Sharks have a heightened sense of indirect touch via water displacement around the shark's body. This is accomplished by the movement of sensory hair cells which are present in the neuromasts that make up the lateral line system. This system is comprised of a series of canals or channels usually visible to the naked eye as a series of pores or lines, these run from the head all the way to the upper lobe of the tail.

Electroreception

The Ampullae of Lorenzini are specialized pores consisting of a small chamber (the ampulla) and a sub-dermal canal which projects outward to the surface of the skin. The ampulla contains hundreds of sensory hair cells. The wall of the canal contains a double layer of connective tissue fibers and epithelial cells, which are tightly joined together to form a high electrical resistance between the inner and outer wall of the canal. The canal and ampulla themselves are filled with a high potassium, low resistance gel that forms an electrical core conductor with a resistance equaling that of seawater.

Fish carry an electrical charge different to that of seawater and so a weak voltage is created (by the movement of positive and negative particles moving back and forth shifting electrons in an attempt to become stable). Because the salt in the water contains both sodium and chlorine ions which can move freely in the water the electricity itself is transported, and this is what the ampullae of lorenzini is able to detect.

6. Name the largest member of the shark family and its maximum adult size.

The Whale Shark grows from 41 to 46 feet (12.5 to 14 meters) long. The largest confirmed specimen was 21.5 metric tons (47,000 lb), about the length and weight of a school bus with all the kids on it.

Whale sharks are not whales, but they are as big as whales and filter feeders (processing plankton) like some whales. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hRMjuoqVgXU

7. Name the most aggressive member of the shark family.

The great white shark is arguably the world's largest known extant macropredatory fish, and is one of the primary predators of marine mammals. It is also known to prey upon a variety of other marine animals, including fish and seabirds. It is ranked first in having the most attacks on humans.

8. Name the predators of the Great White Shark.

The Great White Sharks are apex predators, which means they sit at the very top of the food chain. They patrol the ocean and regulate a healthy marine ecosystem. A great white shark's only predators are:

- Humans (fishing, boat collisions)

- Other Great White Sharks

- Rarely - Orca Whales (amazing video proof)

9. Explain the shark breeding habits.

Biologists have tagged and release thousands of sharks to determine their breeding habits. Their findings reveal that most non migrating shark species return to the same shallow breading grounds every year. After they reach maturity (10 to 14 years) they return to their birth grounds to select a mate. After a ten to twelve months gestation period, a female shark can have a litter of up to eighteen little sharks. After their birth, most species abandon their young and they are left to fend for themselves. The young sharks remain in the shallow waters for two or three years, until they are large enough to defend themselves from bigger predators. Then they head out into the open seas, and the cycle begins again.

10. How do sharks give birth?

Different species of shark give birth in different ways. Some lay eggs, some hatch eggs inside the mother, and others give birth to live young.

11. Discuss with a group the following

a. How to be safe when you are in a shark's natural environment

After watching some of the videos linked from this honor, you will see that shark safety depends on the type of shark you are with. If swimming with Great Whites you will want a shark cage. A chain mail suit can help prevent bites. White skin looks like fish, so a black wetsuit that covers everything helps. The blind shark might clamp on with jaws and suction to a person but is unlikely to cause real harm. Most sharks are completely harmless around humans.

b. Misconceptions of sharks

- Sharks are dangerous! Some are, most are not. 80% of sharks are to placid or small to injure a person. Most live in deep water far from shore and are unlikely to encounter humans.

- Sharks have to keep swimming to breath (some do, some don't)

- Sharks will eat anything! Not so much. Sharks have specific diets they stick too. They use their senses including taste to figure out what is tasty food. If they taste a human (perhaps confused with a sea lion) they tend to release as soon as they realize the human is not their preferred meal.

- Sharks are difficult to kill! Not so much. A shark caught in a net or on a line may die from stress or exhaustion.

c. Dangers of sharks

Shark attacks are one of the biggest fears among ocean swimmers (thanks to Hollywood!) but these fears are almost completely unjustified. Worldwide the number of shark attacks is usually under 10 per year. Riptides, drowning, even cuts from coral are all greater threats.

If you are actually swimming with sharks, take species appropriate precautions.

Humans are a far greater danger to sharks than sharks are a danger to humans. Tens of millions of sharks a year are victims of:

- By-catch: accidentally caught in nets intended other species

- Sport fishing for trophies

- Catch for food sources - shark fin soup, meat etc

- Illegal pouching

12. Do two of the following activities:

a. Take a trip to a local aquarium and learn about the shark daily feeding schedule and habits.

Look for your local aquarium on the net and make sure they have sharks. This option will almost certainly be the most rewarding for your Pathfinders, but it will also require the most work on your part to get it organized. Try to contact the aquarium before setting off on your trip so that you can make arrangements to meet with a staff member there. They are usually very willing to help you, and will be delighted to provide you with information regarding the daily feeding schedule. Note that some zoos have aquariums too, so if a zoo is more convenient than an aquarium, you might want to investigate this possibility.

These honors also have aquarium visits in the requirements, so consider tackling several honors together:

b. Watch a documentary about sharks and identify how sharks hurt and benefit humans.

Watching shark documentaries is tons of fun! Here are several to get started - or just search YouTube for shark documentary full length.

Inside Nature's Giants - Great White Shark (Full Documentary)

National Geographic HD Alaskan Killer Shark

The Reality of a Shark's Life in the Deep Seas (Full Documentary)

You are encouraged to watch the videos for each species as you get a much better idea of each shark than just a photo and short write up.

c. Visit a natural history museum and observe how sharks are displayed within their ecosystem.

Look for the nearest Natural History Museum on the internet and be sure to call and ask if they have sharks.

d. Create a display of 10 photos and information about sharks including significant information learned in this honor.

Poster boards about the ten types of sharks you studied would work. Display at school or a Pathfinder fair. Everyone loves and fears sharks so your display should be a hit.

e. Create a game that assists others in learning about sharks. You may model the game after popular card or board games.

This can be a very enjoyable activity, not only for learning about sharks, but also in learning about creating games. When creating the game, try to keep it balanced. It's OK to incorporate an element of chance into the game, but you should focus more on knowledge - that is, the more you know about sharks, the better chance you have of winning. A game where whoever draws the Great White Shark is pretty much the guaranteed winner relies too heavily on chance, and not enough on skill.

Consider other elements of game-play as well. Games are more enjoyable when a person who is "losing" still has a realistic chance of winning. Games are less enjoyable when whoever is winning becomes unstoppable, and less enjoyable still if the outcome is known well before the game ends. That's like a slow death.

Another thing to watch for is a game in which a player gets "out" before the game ends. No one likes to sit on the sidelines while everyone else has fun. If your game must sideline a player, make sure that the "out" is as brief as possible.

Be sure to write the rules down so that there is no temptation to change them to your advantage during game play (that's cheating). Feel free to jot down ideas for rule changes during the game, but don't try to get them approved during the game.

If you are teaching this honor to a group, feel free to make the game development a "homework" (homeplay?) assignment. It's also OK for people to work in small groups to develop the game. Just be sure to come back together as a group to play all the games. After all, what fun is a game that no one plays, and if no one plays the game, who will have learned anything about sharks?

Don't limit yourself to table games either. If you can think of a playground game that helps people learn about sharks, that will incorporate physical activity into the learning process. Exercise is good, and it's even better when it expands knowledge!

Here are a few ideas to get you started, but remember, there are a lot of games out there that you can use as a model. If you don't like the game these are based upon, you will probably not like the shark version any better, so if you are going to model your game after an existing one, choose a game you like.

Go Fish

Since sharks are fish, why not create a deck of "go fish" cards for sharks? You will need one card per shark, and you will need to divide them into groups or "suits" of 3-4 sharks per group. We leave it to you to figure out how to distribute them, but you could group them by genus, aggression, habitat, or any other logical way you can think of to group them. The card should have a photo of the shark plus its name, and the names of the other sharks in its group.

Deal part of the cards to each player (you decide how many when you write the rules, but 5 is not a bad place to start). The first player begins by asking any other player "have you a Great White?" (or some other species). The player cannot ask for a species unless she already holds another species in that group. If the player who is asked the question has that card, he must hand it over. Otherwise he says "Go fish" (or "Go shark!" if you prefer). At that point, the player must draw a new card from the deck and her turn ends. When a player has all the cards in a group, he may lay them on the table (face up) and no one can take that card away. When any player runs out of cards, the round is finished, and each player gets a point for each group of sharks they completed.

To make the game more difficult (and more flexible), omit the names of the other sharks in the group. Instead, list specific information about each shark on its card, and try to get a set by knowing certain things about the sharks. In this version, you could make a set of any four sharks belonging to a genus, any four living in the Pacific, any four that give live birth, etc. This version will be far more educational, as each player will end up learning different ways that sharks can be grouped. The more data you have on the card, the more ways you will have to group them into sets.

Stratego

If you are familiar with the game of Stratego, it is not difficult to see how you could use sharks instead of soldiers to play the game. Simply rank the sharks from least powerful to most powerful, and play the game as normal. You may wish to create a board which, unlike Stratego, is mostly water with a few land masses dividing the two sides. You could also name the waterways on your board and not allow certain sharks into certain waters based on the natural ranges of the sharks. Replace the fortress with a shark cage (or anything else you can think of).

Shark Balderdash

Make cards with real facts about sharks (obscure ones) and underline keywords to be left out. The person who's turn it is pulls a card and reads the fact without the keywords. "Great White Sharks live in ___ oceans. The other players fill in papers with what they think the answer is, or what they think others will vote for. The person whose turn it is fills in a card with the real answer too.

The person then reads all the answers and players vote for their favorite. One point is awarded for guessing correctly and one point for everyone that likes your made up answer. Most points at the end of the cards wins.