AY Honors/Hot Air Balloons/Answer Key

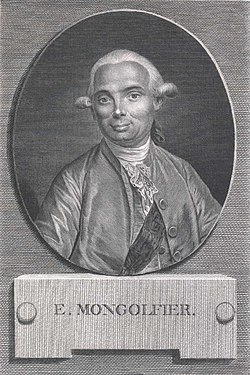

Michel Montgolfier (26 August 1740 – 26 June 1810) and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier (6 January 1745 – 2 August 1799) were the inventors of the montgolfière, globe airostatique or hot air balloon. The brothers succeeded in launching the first manned ascent to carry a young physician and an audacious army officer into the sky. They were later ennobled with their father and brothers and sisters as de Montgolfier.

Public demonstrations

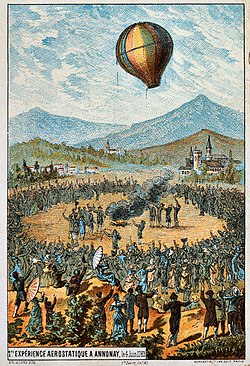

The brothers decided to make a public demonstration of a balloon in order to establish their claim to its invention. They constructed a globe-shaped balloon of sackcloth with three thin layers of paper inside. The envelope could contain nearly 790 m³ (28,000 cubic feet) of air and weighed 225 kg (500 lb). It was constructed of four pieces (the dome and three lateral bands), and held together by 1,800 buttons. A reinforcing "fish net" of cord covered the outside of the envelope.

On 4 June 1783, they flew this craft as their first public demonstration at Annonay in front of a group of dignitaries from the Etats particulars. Its flight covered 2 km (1.2 mi), lasted 10 minutes, and had an estimated altitude of 1.600 - 2.000m (5,200 - 6,600 ft). Word of their success quickly reached Paris. Etienne went to the capital to make further demonstrations and to solidify the brothers' claim to the invention of flight. Joseph, given his unkempt appearance and shyness, remained with the family. Etienne was the epithome of sober virtues ... modest in clothes and manner...& He was dressed stylishly in black.

In collaboration with the successful manufacturer, Jean-Baptiste Réveillon, Etienne constructed a 37,500 cubic foot envelope of taffeta coated with a varnish of alum. The balloon was sky blue and with golden flourishes, signs of the zodiac, suns. The design was the influence of Réveillon, a wallpaper maker. The next test was on the 11th of September from the parc la Folie Titon, close to the house of Réveillon. There was some concern about the effects of flight into the upper atmosphere on living creatures. The king proposed to launch two criminals, but it is most likely that the inventors decided to send animals aloft first.

On 19 September 1783 the Aerostat Réveillon was flown with the first living beings in a basket attached to the balloon: a sheep, called Montauciel (Climb-to-the-sky), a duck and a rooster. This demonstration was performed before a huge crowd at the royal palace in Versailles, before King Louis XVI of France, Queen Marie Antoinette.& The flight lasted approximately eight minutes, covered two miles, and obtained an altitude of about 1500 feet. The craft landed safely after flying.

Human flight

With the successful demonstration at Versailles, and again in collaboration with Réveillon, Etienne started construction of a 60,000 cubic foot balloon for the purpose of making flights with humans. The craft was 75 feet tall and 46 feet in diameter. The balloon was tested in tethered flights on 15 October by Pilâtre de Rozier, a twenty-six-year-old physician, who offered his services. On the 17 October the experiment was repeated before a group of scientists and 19 October Rozier and André Giroud de Villette, a wallpaper manufacturer from Madrid, reached 324 feet within 15 seconds along retaining ropes.

On 21 November the first free flight by humans was made by Pilâtre, together with an army officer, the marquis d'Arlandes. The flight began near the Bois de Boulogne in the parc of the Château de la Muette in the western outskirts of Paris. They flew aloft about 3,000 feet above Paris for a distance of nine kilometres. After 25 minutes the machine landed between the windmills, outside the city ramparts, on the Butte-aux-Cailles. Enough fuel remained on board at the end of the flight to have allowed the balloon to fly four to five times as far. However, burning embers from the fire were scorching the balloon fabric and had to be daubed out with sponges. As it appeared it could destroy the balloon, Pilâtre took off his coat to stop the fire.

The ascensions made a sensation. Numerous engravings commemorated the events. Chairs were designed with balloon backs, and mantel clocks were produced in enamel and gilt-bronze replicas set with a dial in the balloon. One could buy crockery decorated with naive pictures of balloons.

Following launches

In 1766, the British scientist Henry Cavendish had discovered hydrogen, by adding sulphuric acid to iron, tin, or zinc shavings. The development of gas balloons proceeded almost in parallel with the work of the Montgolfiers. This work was led by M. Charles. On the 27th of August a hydrogen balloon was launched from the Champ de Mars in Paris. Six thousand people paid for a seat. A downpour of rain ended the show. On December, the 1st, prof. Charles went up into the sky twice.

Work on each type of balloon was spurred on by the knowledge that there was a competing group and alternative technology. For a variety of reasons, including the fact that the French government chose to put a proponent of hydrogen in charge of balloon development, hot air balloons were superseded by hydrogen balloons. Hydrogen balloons became the predominant technology for the next 180 years.

Hydrogen balloons were used for all major ballooning accomplishments such as the crossing of the English Channel on 7 January 1785, by the tireless aviators Jean-Pierre Blanchard and Dr. John Jeffries, from Boston.

Competing claims

Some claim that the hot air balloon was actually invented some 74 years earlier by the Portuguese priest Bartolomeu de Gusmão.& A description of his invention was published in 1709, in Vienna, and another one that was lost was found in the Vatican (circa 1917).& However, this claim is not generally recognized by aviation historians outside the Portuguese speaking community, in particular the FAI.

- ↑ S. Schama (1989) Citizens. A Chronicle of the French Revolution, p. 125.

- ↑ C.C. Gillispie, p. 92-3.

- ↑ Reis, Fernando. Bartolomeu de Gusmão.Ciência em Portugal. Centro Virtual Camões in Portuguese

- ↑ Gusmao, Bartolomeu de. Reproduction fac-similé d'un dessin à la plume de sa description et de la pétition addressée au Jean V. (de Portugal) en langue latine et en écriture contemporaine (1709) retrouvés récemment dans les archives du Vatican du célèbre aéronef de Bartholomeu Lourenco de Gusmão "l'homme volant" portugais, né au Brésil (1685-1724) précurseur des navigateurs aériens et premier inventeur des aérostats. 1917 (Lausanne : Impr. Réunies S. A..) in French and Latin