Especialidades JA/Tradición maorí/Respuestas 2

Nivel de destreza

1

Año

Desconocido

Version

13.02.2026

Autoridad de aprobación

División Norteamericana

Waiata is the Māori word for song.

In the Māori language, Tāne means "man".

Various Māori traditions recount how their ancestors set out from a mythical homeland in great ocean-going canoes (or waka). Some of these traditions name the homeland as Hawaiki.

Among these is the story of Kupe, who had eloped with Kuramarotini, the wife of Hoturapa, the owner of the great canoe Matahourua, whom Kupe had murdered. To escape punishment for the murder, Kupe and Kura fled in Matahourua and discovered a land he called Aotearoa ('long-white-cloud'). He explored its coast and killed the sea monster Te Wheke-a-Muturangi, finally returning to his home to spread news of his newly discovered land.

Other stories of various other tribes report migrations to escape famine, over-population, and warfare. These were made in legendary canoes, the best known of which are Aotea, Arawa, Kurahaupō, Mataatua, Tainui, Tākitimu, and Tokomaru. Various traditions name numerous other canoes. Some, including the Āraiteuru, are well known; others including the Kirauta and the sacred Arahura and Mahangaatuamatua are little known. Rather than arriving in a single fleet, the journeys may have occurred over several centuries.

An important early collector and preserver of Māori traditions was the surveyor and ethnologist Stephenson Percy Smith. He believed that while the Polynesian traditions may have been flawed in detail, they preserved the threads of truth which could be recovered using a method already well established for Hawaiian traditions by Fornander (1878-1885). This method involved seeking out common elements of tradition from different sources, and aligning these to genealogies to give a time frame for the events. Abraham Fornander, Smith, and others used this method to reconstruct the migrations of the Polynesians, tracing them back to a supposed ancient homeland in India.

S. Percy Smith used the Fornander method, combining disparate traditions from various parts of New Zealand and other parts of Polynesia, to derive a now discredited version of Māori migration to New Zealand -- the 'Great Fleet' hypothesis. Through an examination of the genealogies of various tribes, he came up with a set of precise dates for his 'Great Fleet' and the explorers that he and others posited as having paved the way for the fleet.

According to Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, "Smith’s account went as follows. In 750 AD the Polynesian explorer Kupe discovered an uninhabited New Zealand. Then in 1000–1100 AD, the Polynesian explorers Toi and Whātonga visited New Zealand, and found it inhabited by a primitive, nomadic people known as the Moriori. Finally, in 1350 AD a ‘great fleet’ of seven canoes – Aotea, Kurahaupō, Mataatua, Tainui, Tokomaru, Te Arawa and Tākitimu – all departed from the Tahitian region at the same time, bringing the people now known as Māori to New Zealand. These were advanced, warlike, agricultural tribes who destroyed the Moriori." The great fleet scenario won general acceptance, its adherents even including the famous Māori ethnologist Te Rangi Hīroa (Sir Peter Buck), and was taught in New Zealand schools. However it was effectively demolished during the 1960s by the ethnologist David Simmons, who showed that it derived from an incomplete and indiscriminate study of Māori tradition as recorded in the 19th Century. Simmons also suggests that some of these 'migrations' may actually have been journeys within New Zealand.

Historian Rāwiri Taonui, writing in 2006 for the website Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, accuses Smith of falsification: "The Great Fleet theory was the result of a collaboration between the 19th-century ethnologist S. Percy Smith and the Māori scholar Hoani Te Whatahoro Jury. Smith obtained details about places in Rarotonga and Tahiti during a visit in 1897, while Jury provided information about Māori canoes in New Zealand. Smith then ‘cut and pasted’ his material, combining several oral traditions into new ones. Their joint work was published in two books, in which Jury and Smith falsely attributed much of their information to two 19th-century tohunga, Moihi Te Mātorohanga and Nēpia Pōhūhū" (Taonui 2006).

These are the seven legendary canoes proposed by historian Stephenson Percy Smith in his "Great Fleet hypothesis." Various traditions name numerous other canoes.

| Name of Canoe | Regional Traditions | Associated Iwi or Hapu |

|---|---|---|

| Aotea | Taranaki, Waikato | Ngā Rauru Kītahi, Ngāti Ruanui |

| Te Arawa | Bay of Plenty, East Coast, Waikato | Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Te Arawa |

| Kurahaupō | Northland, Taranaki | Ngati Apa, Ngāti Kurī, Ngati Ruanui |

| Mataatua | Bay of Plenty, Northland | Ngā Puhi, Ngāi Te Rangi, Ngāti Awa, Ngāti Pūkenga, Te Whakatōhea |

| Tainui | Auckland, Bay of Plenty, Taranaki, Waikato | Ngāti Raukawa Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Maru, Ngāti Pāoa, Ngāti Rongoū, Ngāti Tamaterā, Ngāti Whanaunga |

| Tākitimu | Bay of Plenty, East Coast, South Island | Muriwhenua, Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāti Ranginui, Ngāi Tahu |

| Tokomaru | Taranaki | Ngati Tama, Ngati Mutunga, Ngati Rāhiri, Manukorihi, Puketapu, Te Atiawa, Ngati Maru |

Rangitoto Island is a volcanic island in the Hauraki Gulf near Auckland, New Zealand. Rangitoto is Māori for 'Bloody Sky', with the name coming from the full phrase Nga Rangi-i-totongia-a Tama-te-kapua ('The days of the bleeding of Tama-te-kapua').

A hui can be called for many reasons, including a wedding, birth, funeral, or even a meeting to discuss community decisions.

If you arrive at the marae before the rest of your group, wait for them before entering. Visitors are always welcomed in groups, and to enter all by yourself is a violation of protocol. When your whole group has arrived, you may enter the marae, and you will be welcomed in a powhiri ceremony.

It might be a good idea to bring a small notebook and pen along so you can take notes about what is happening. A hui follows a prescribed structure. If you do not understand everything that happens, ask your host afterwards.

As described previously, mate means "death" in Māori.

Tangihanga, or more commonly, Tangi, is a Māori funeral rite. Tangihanga takes place at a marae, and each manuhiri (visiting group) receives a pohiri (formal greeting). Some tribes will not perform a pohiri after dark, so the visitors must arrive before dusk.

A collection is taken up to defray the costs of embalming, to defray the costs of the marae, or both.

On the final night of the tangihanga, people tell stories, sing, and tell jokes to help cheer the grieving family. Burial takes place the following day. After the body is lowered into the grave, people are given an opportunity to say a final farewell. Then everyone present files by the grave and throws in either a flower or a handful of soil.

If the deceased lived near the cemetery, the people go their after the burial and bless the house. Otherwise, this is done sometime later. After the house blessing, a Hakari (final feast) is held, during which people will speak or perform. The Hakari is a celebration and affirmation of life.

Food was considered communal property among the Māori. It was distributed by an official who was placed in charge of the food warehouse. Communal ownership of food prevented an unlucky fisherman (and his family) from going hungry.

Before contact with Europeans was established, the Māori diet consisted primarily of vegetables, though fish was not an uncommon food. They correctly believed that diet affected health, and that regular bowels were an important aspect of general health.

The Māori ate two meals per day. Breakfast was eaten a few hours after waking, and dinner was eaten in the early evening. A light snack sufficed for lunch.

The history of individual tribal groups is kept by means of narratives, songs and chants, hence the importance of music, story and poetry. Oratory, the making of speeches, is especially important in the rituals of encounter, and it is regarded as important for a speaker to include allusions to traditional narrative and to a complex system of proverbial sayings, called whakataukī.

Formal speeches are delivered at marae, and as the orator speaks, he re-enacts portions of the Māori creation story when Tāne separated the earth (his mother) from the sky (his father), thus allowing himself and his siblings to see light. During the oration, this re-enactment represents light (or understanding) coming to the people.

In some cases, guests to a marae may spend the night. When this happens, the hosts provide mattresses on the floor, but no beds. Everyone sleeps in a common room, and the guests are not separated by gender.

It is considered very bad manners to step over the body of a sleeping person. Stepping over a person's head is absolutely forbidden, as a person's head is considered the most tapu (sacred) part of a person.

The Māori also observe customs to determine where guests and hosts sleep. The guests sleep in the tapu part of the house, which is located along the right wall as one enters the building. Hosts sleep on the noa (common) side which is on the left. Further, the chief among the visitors will sleep in the corner near a window, and visitors are ordered in a way which is related to the order in which they speak.

Of the Māori who claim a religion, 98% today identify themselves as Christian. The largest denominations in the 2006 census were Anglicans (about 14% of the population), Catholics (about 12%), Presbyterians (about 9%), and Methodists (about 3%). Around 5% of the population identified themselves as Christian without associating themselves with any particular denomination.

For the purposes of this requirement though, we will not consider these as "Māori" religions, as they were introduced by the Europeans. "The" two Māori religions in use today could arguably be the original Māori religion practiced before the Europeans arrived, and Ratana.

Māori Religion

Traditional Māori religion, that is, the pre-European belief system of the Māori, was little modified from that of their tropical Eastern Polynesian homeland (Hawaiki Nui), conceiving of everything, including natural elements and all living things as connected by common descent through whakapapa or genealogy. Accordingly, all things were thought of as possessing a life force or mauri. As an illustration of this concept of connectedness through genealogy, consider a few of the major personifications of pre-contact times: Tangaroa was the personification of the ocean and the ancestor or origin of all fish; Tāne was the personification of the forest and the origin of all birds; and Rongo was the personification of peaceful activities and agriculture and the ancestor of cultivation.

Certain practices are followed that relate to traditional concepts like tapu. Certain people and objects contain mana - spiritual power or essence. In earlier times, tribal members of a higher rank would not touch objects which belonged to members of a lower rank. This was considered "pollution" and persons of a lower rank could not touch the belongings of a highborn person without putting themselves at risk of death.

Tapu can be interpreted as "sacred", as "spiritual restriction" or "implied prohibition"; it involves rules and prohibitions. There are two kinds of tapu, the private (relating to individuals) and the public tapu (relating to communities). A person, an object or a place, which is tapu, may not be touched by human contact, in some cases, not even approached. A person, object or a place could be made sacred by tapu for a certain time.

In pre-contact society, tapu was one of the strongest forces in Māori life. A violation of tapu could have dire consequences, including the death of the offender through sickness or at the hands of someone affected by the offence. In earlier times food cooked for a person of high rank was tapu, and could not be eaten by an inferior. A chief's house was tapu, and even the chief could not eat food in the interior of his house. Not only were the houses of people of high rank perceived to be tapu, but also their possessions including their clothing. Burial grounds and places of death were always tapu, and these areas were often surrounded by a protective fence.

Ratana

The Ratana movement is a Māori religion and pan-tribal political movement founded by Tahupotiki Wiremu Ratana in early 20th century New Zealand. The Ratana Church has its headquarters at the settlement of Ratana, near Wanganui.

The first decades of the twentieth century were a low point for Māori, both in numbers and in spirit. During the nineteenth century, Māori lost their tribal way of life, lands, traditional religion and their mana. Christianity had been accepted, but the missionaries had acted as chaplains to the colonial forces fighting against their Christian converts who were defending their land. Many Māori regarded the missionary clergy as agents of the Government in a deep-laid plot to subjugate the Māori people.

From the 1860s, prophets such as Te Ua Haumene, Te Kooti, Te Whiti o Rongomai and Tohu Kakahi put the words of the Bible into terms Māori could understand. The dislocation of colonialism had strained Māori society and led to a belief in a saviour to come.

In 1918, Tahupotiki Wiremu Ratana saw a vision, which he regarded as divinely inspired, asking him to preach the gospel to the Māori people, to destroy the power of the tohunga and to cure the spirits and bodies of his people. Until 1924, he preached to increasingly large numbers of Māori, and T.W. Ratana established a name for himself as the "Māori Miracle Man". Initially, the movement was seen as a Christian revival but it soon moved away from mainstream churches. On 31 May 1925, Te Haahi Ratana (The Ratana Church) was formally established as a separate church, with its founder acknowledged as Te Mangai or the mouthpiece of God. Hostile attitudes have caused the church to be guarded towards its teaching and founder.

Rangi and Papa are the primordial parents, the sky father and the earth mother who lie locked together in a tight embrace. They have many children all of which are male, who are forced to live in the cramped darkness between them. These children grow and discuss among themselves what it would be like to live in the light. Tūmatauenga, the fiercest of the children, proposes that the best solution to their predicament is to kill their parents.

But his brother Tāne (or Tāne-mahuta) disagrees, suggesting that it is better to push them apart, to let Rangi (their father) be as a stranger to them in the sky above while Papa (their mother) will remain below to nurture them. The others put their plans into action—Rongo, the god of cultivated food, tries to push his parents apart, then Tangaroa, the god of the sea, and his sibling Haumia-tiketike, the god of wild food, join him. In spite of their joint efforts Rangi and Papa remain close together in their loving embrace. After many attempts Tāne, god of forests and birds, forces his parents apart. Instead of standing upright and pushing with his hands as his brothers have done, he lies on his back and pushes with his strong legs. Stretching every sinew Tāne pushes and pushes until, with cries of grief and surprise, Ranginui and Papatuanuku are forced apart.

And so the children of Rangi and Papa see light and have space to move for the first time. While the other children have agreed to the separation Tāwhirimātea, the god of storms and winds, is angered that the parents have been torn apart. He cannot not bear to hear the cries of his parents nor see the tears of the Rangi as they are parted, he promises his siblings that from henceforth they will have to deal with his anger. He flies off to join Rangi and there carefully fosters his own many offspring who include the winds, one of whom is sent to each quarter of the compass. To fight his brothers, Tāwhirimātea gathers an army of his children—winds and clouds of different kinds, including fierce squalls, whirlwinds, gloomy thick clouds, fiery clouds, hurricane clouds and thunderstorm clouds, and rain, mists and fog. As these winds show their might the dust flies and the great forest trees of Tāne are smashed under the attack and fall to the ground, food for decay and for insects.

Then Tāwhirimātea attacks the oceans and huge waves rise, whirlpools form, and Tangaroa, the god of the sea, flees in panic. Punga, a son of Tangaroa, has two children, Ikatere father of fish, and Tu-te-wehiwehi (or Tu-te-wanawana) the ancestor of reptiles. Terrified by Tāwhirimātea’s onslaught the fish seek shelter in the sea and the reptiles in the forests. Ever since Tangaroa has been angry with Tāne for giving refuge to his runaway children. So it is that Tāne supplies the descendants of Tūmatauenga with canoes, fishhooks and nets to catch the descendants of Tangaroa. Tangaroa retaliates by swamping canoes and sweeping away houses, land and trees that are washed out to sea in floods.

Tāwhirimātea next attacks his brothers Rongo and Haumia-tiketike, the gods of cultivated and uncultivated foods. Rongo and Haumia are in great fear of Tāwhirimātea but, as he attacks them, Papa determines to keep these for her other children and hides them so well that Tāwhirimātea cannot find them. So Tāwhirimātea turns on his brother Tūmatauenga. He uses all his strength but Tūmatauenga stands fast and Tāwhirimatea cannot prevail against him. Tū (or humankind) stands fast and, at last, the anger of the gods subsided and peace prevailed.

Tū thought about the actions of Tāne in separating their parents and made snares to catch the birds, the children of Tāne who could no longer fly free. He then makes nets from forest plants and casts them in the sea so that the children of Tangaroa soon lie in heaps on the shore. He made hoes to dig the ground, capturing his brothers Rongo and Haumia-tiketike where they have hidden from Tāwhirimātea in the bosom of the earth mother and, recognising them by their long hair that remains above the surface of the earth, he drags them forth and heaps them into baskets to be eaten. So Tūmatauenga eats all of his brothers to repay them for their cowardice; the only brother that Tūmatauenga does not subdue is Tāwhirimātea, whose storms and hurricanes attack humankind to this day.

- before 1893

- Maui Pomare, a Māori youth is baptized as a Seventh-day Adventist in Napier.

- 1893

- Pomare travels to the U.S. to study medicine at the Seventh-day Adventist Church medical college at Battle Creek, Michigan.

- 1895

- Pomare publishes a pamphlet in the Māori language arguing that the seventh day is the Sabbath.

- 1900

- Pomare returns to New Zealand and was selected to serve as Māori Health Officer in the Department of Health. In this role he undertook a number of major campaigns to improve Māori health and met with considerable success. He eventually leaves the Adventist Church.

- 1902

- First Adventist school opens in New Zealand at Ponsonby

- 1903

- Adventist school opened in Christchurch. Both schools fail due to lack of resources.

- 1903-1905

- Adventist schools opened in Napier, Lower Hutt, Petone and New Plymouth.

- 1908

- School opened near Cambridge and named "Pukekura", Māori for "I love the place."

- 1913

- Pukekura relocated to its current site at Longburn Adventist College near Palmerston North.

- next 100 years?

In the book Tikanga Māori Hirini Moko Mead describes the Māori attitude to religion this way:

|

Tukutuku

A tukutuku is a woven wall hanging traditionally made from flax. New Zealand flax describes common New Zealand perennial plants Phormium tenax and Phormium cookianum, known by the Māori names harakeke and wharariki respectively. They are quite distinct from Linum usitatissimum, the Northern Hemisphere plant known as flax (and also known as linseed). The genus was given the common name 'flax' by Anglophone Europeans as it too could be used for its fibres.

Tukutuku panels are a traditional Māori art form. They are decorative wall panels that were once part of the traditional wall construction used inside meeting houses. Originally tukutuku were made by creating a latticework of vertically and horizontally placed dried stalks of kākaho, the creamy-gold flower stalks of toetoe grass, and kākaka, long straight fern stalks, or wooden laths of rimu or tōtara, called variously kaho tara, kaho tarai or arapaki.

These panels were lashed or stitched together. This was done by people working in pairs from either side, using the rich yellow strands of pīngao, white bleached or black-dyed kiekie, and sometimes harakeke, to create a range of intricate and artistic patterns. Stitches were combined to form a variety of patterns. Groups of single stitches created patterns such as tapuae kautuku, waewae pakura, whakarua kopito and papakirango. Some of the traditional cross stitched patterns are poutama, waharua, purapura whetu or mangaroa, kaokao, pātikitiki, roimata toroa and niho taniwha. In some situations, a central vertical stake, tumatahuki, was lashed to the panel to aid its strength and stability.

This method of construction created a warm, insulating type of decorative wallboard. Later, painted wooden slats or half-rounds were used for the horizontal element. Today, however, such dry flammable wallboards would fail to meet modern building regulations, and they are no longer used in construction. When used nowadays, tukutuku panels are created for their aesthetic appeal and attached to structurally approved building materials.

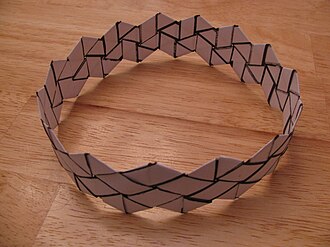

Tipare

A tipare is a headband woven from flax. You can make one from paper if you do not have access to flax, or you could use any broad-leaved grass. These instructions are adapted from those written by Catherine Brown in an article written in 1965. If using flax, run the length of the flax over the blade of a knife to soften it up. To make a tipare from paper, start by cutting it into strips 1 cm wide. You might want to practice on paper before trying this in flax, but that's up to you. The tipare illustrated below was made in paper (with the edges marked) to make it easier to understand the photos.

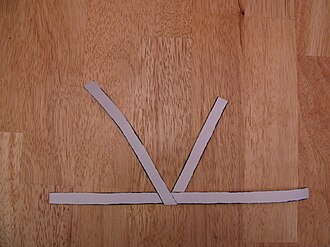

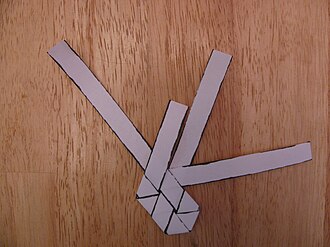

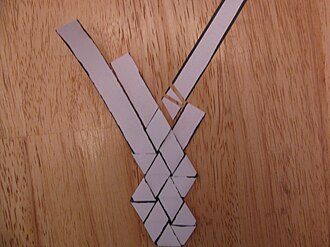

| Mark a 60° angle on one strip, not in the center, but off to either side. Fold the strip into a V along the 60° line with the left side over the right. This angle is critical, so make it as close to 60° as you can. Place a second strip in the bottom of the V as shown, but do not center it in the notch of the V. If you make the V fold in the center or center the second strip on the notch, the two ends of the strip will run out at the same time and you will have two splices in the same vicinity. Offsetting them from the center avoids this problem. |

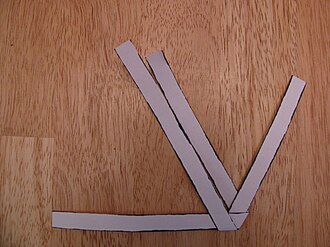

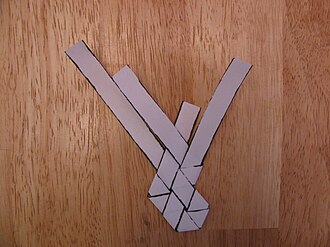

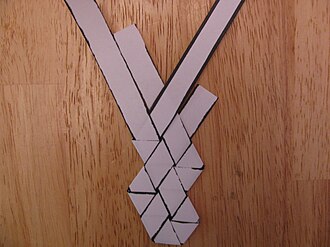

| Fold the right side of the horizontal strip behind the right leg of the V so that it lies parallel to the left leg of the V. If the 60° angle was folded properly, the second strip should fall right into place. If it does not, check the angle of that first fold again. |

|

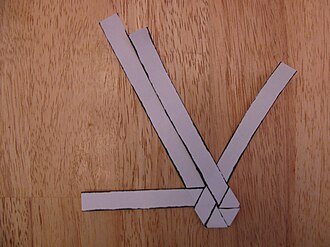

Fold the other horizontal strip over the left leg of the V so that it runs along and parallel to the right leg of the V. Tuck it beneath the second strip it crosses. You should end up with a double-V, consisting of two outer legs and two inner. The rest of the weaving process will always begin with one of the outer legs. Choosing which is perhaps the most difficult part of making a tipare, but for now, choose the one on the right and fold it behind the V as shown on the right. Make sure that it goes behind two strips and over the third. |

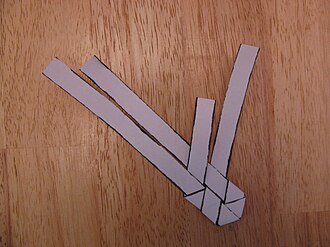

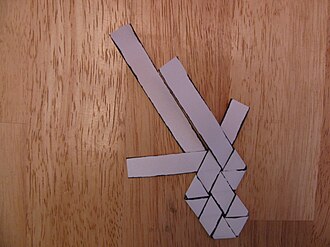

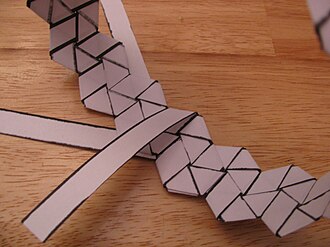

| Now take that same strip and fold it around the back of the strip it was just tucked in front of. Weave it in front of the adjacent strip. |

| Fold the strip farthest to the left behind the tipare, and weave it in front of the strip farthest to the right. |

| Fold that same strip behind the right-most strip and weave it in front of the next. The next step is to take one of the outer strips and fold it into a horizontal position, but which strip? As you make a tipare, this will be the question that vexes you after every fold, and if you get it wrong, the tipare will come out wrong as well. Look at the photo to the left. If you fold the strip on the left, you will continue the edge made along the left side. If you fold the strip on the right, you will form a point on the right side. Always choose the strip that will form a point. |

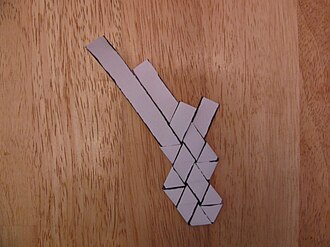

| There — we have chosen the strip that will form a point and have folded it horizontally. It was woven over the front of the outer strip on the other side and then folded around it and woven again. |

| But now we've run out of strip. Cut the strip along the edge of the tipare, and cut the tip of a new strip off at the same angle. The ends of these two strips are positioned next to the pieces from which they were cut. Discard them. |

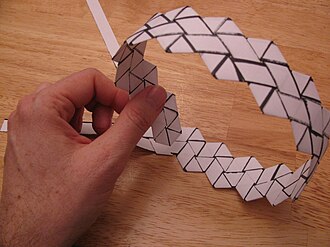

| Now tuck the new strip into the weave, pushing it in until it stops. You should be able to push it in pretty far. There is no need for glue or any other sort of adhesive. The weave itself will hold the strip in place. Continue weaving until you have a long enough piece of tipare to wrap around the head of the intended tipare wearer. |

| Bend the tipare around forming a loop. Line up the beginning of the tipare with the points on the unwoven end (photo on the left). Fold the next strip on the unwoven end around the beginning, cut it to length, and tuck it into the weave (photo on the right). |

| Continue weaving the loose ends into the tipare, cutting them off at the proper length and tucking them into the weave. When the last strip is woven into place, the tipare is finished. Crown the recipient. |

Preparations

- Harvesting

Flax should be cut in a certain way. Traditional weavers were conservationists — they looked after the flax plant from its growth, after harvesting, and through the whole process of usage. Māori treasure the flax plant, presumably because it was a major resource for them for many things. Never cut the center (baby blade), nor the two on either side - (mother and father). Cutting these blades will kill the plant. Return all unused flax (harekeke) and wastage to the plant cut up as mulch. Don't harvest in the rain or the flax will shrink too much after use. When cutting the flax make sure you cut on an angle. This is to make sure that rain and debris does not settle in the roots and spoil the plant. Keep the flax usable for a few days by placing ends in a bucket of water as soon as you return home. Keep it out of the direct sun. To keep it longer boil it as described in the Dying Flax section below.

- Tools

A steel bar or using the back or blunt side of a butter knife is used to soften the strips. Traditionally a mussel shell was used. The shell or blunt edge is pulled along the dull side of the flax blade and this also helps release the moisture content. Flax woven articles do shrink to a beautiful golden colour as they dry. Flax is used green or is softened by boiling as described below. Using boiled flax reduces the shrinkage in the finished article.

- Dying Flax

Bring a pot of water to a boil, and add your flax, prepared as above in the Tools section. Boil the flax for 5 minutes and then dry it. This can be kept for later use or dyed whenever you are ready. Fill a sink or bucket with warm water and put the boiled, dry flax in the water to soften it. You can now weave with it or dye it. Use a large pot and fill two thirds with water and then add the dye to the boiling water. The amount used is up to the weaver. Return it to a boil. Finally, place your softened flax into the dye - use rubber gloves. Once the right colour is obtained, add a good handful of salt. This will set the dye or fix it to the flax fibres. Allow the dyed flax to dry, but not in the direct sun. Once it is dry you can then go through the process to soften it and weave it. If you use it straight after dying you will need to wear disposable gloves unless you want your hands to be dyed as well. But once it has dryed it will set the dye. Some people use vinegar to fix the dye. For the dye itself you can use cordial drink concentrates (Thriftee and Koolaid are brands available in New Zealand and they don't need a fixer as the citric acid in the drink concentrate and set the dye). You can mix these colours to get the one you want.

In the Māori language, speakers distinguish correct use of the number of people referred to in all aspects of the language. For example, everyday greetings take different forms depending on the number of people greeted:

- Tēnā koe: hello (to one person)

- Tēnā kōrua: hello (to two people)

- Tēnā koutou: hello (to more than two people

A Hongi is a traditional Māori greeting in New Zealand. It is done by pressing one's nose to another person at an encounter.

It is still used at traditional meetings among members of the Māori people and on major ceremonies.

In the hongi, the ha or breath of life is exchanged and intermingled.

Through the exchange of this physical greeting, you are no longer considered manuhiri (visitor) but rather tangata whenua, one of the people of the land. For the remainder of your stay you are obliged to share in all the duties and responsibilities of the home people. In earlier times, this may have meant bearing arms in times of war, or tending crops of kumara (sweet potato).

When Māori greet one another by pressing noses, the tradition of sharing the breath of life is considered to have come directly from the gods.

In Māori folklore, woman was created by the god Tane moulding her shape out of the earth. Then Tane (meaning male) embraced the figure and breathed into her nostrils. She then sneezed and came to life. Her name was Hineahuone (earth formed woman). Tane later had a child with her and when she found out he was her father she fled to the underworld where she was believed to look after the spirits of the dead.

Māori Stick Game

In the Māori stick game, the participants sit in a circle and each person holds two sticks. Music begins, and the sticks are then rhythmically rapped on the floor or tapped together in beat with the music. See http://www.uen.org/Lessonplan/preview.cgi?LPid=13919 for more details.

Poi

Poi is a form of juggling or object manipulation employing a ball suspended from a length of rope which is held in hand and swung in circular patterns, comparable to club-twirling. Poi spinning originated with the Māori people of New Zealand (the word poi means "ball" in Māori) as a means of promoting increased flexibility, strength, and coordination -in particular, the dexterity of the wrist- and as an exercise of movements central to the use of hand weapons, including the patu, mere, and kotiate.

Some popular poi tricks include: reels, weaves, fountains, crossers, windmills, butterflies, stalls, and wraps. Split time and split direction moves are possible, and some of the more difficult moves require a considerable amount of manual dexterity, coordination and forearm strength to accomplish.

There are several basic classes of trick. The two poi are usually spun in parallel planes, and can be spun in the same direction (weaves) or opposite directions (butterflies). Moves such as stalls and wraps can change direction of one (or both poi) to change between these two classes.

Flying Kites

Māori people were experts a building and flying kites. Kites were made from the flower stalks of toetoe grass (Cortaderia fulvida) and decorated with shells (such as the abalone), feathers, and foliage. Some kites were big enough to carry a person, and these were sometimes used to lift warriors over the walls of enemy defences.

Puppetry

The Māori made Karetao (puppets) to use in story-telling. The Karetao were carved figures featuring a handle at the bottom (and held by one hand) and movable arms attached to strings (operated by the other hand).

Other Games

Other games include

- Spinning Tops

- Wrestling

- Throwing Darts

- Memorization Games

String Figures

String figures are designs made on the hands and fingers using a piece of string tied into a circle. In the west, an example of this would be the cat in the cradle.

For instruction on making several Māori string figures, see http://www.tki.org.nz/r/hpe/exploring_te_ao_kori/stringgames/index_e.php

Stilts

Stilts are long poles with foot pegs mounted to them. The stilt-walker stands on the pegs, and the poles extend upwards past the shoulders. The walker wraps his arms around the poles and as he lifts his left foot, uses his left hand to lift the pole. The foot pegs are often movable, and it is best to learn to walk with stilts with the pegs set low to the ground. As the Pathfinder develops skill, the foot pegs can be raised.

The word pā (pronounced pah) refers to a Māori village, generally one from the 19th century or earlier that was fortified for defense. In Māori society, a great pā represented the mana of a tribal group, as personified by a chief or rangatira.

Nearly all pā were built in defensible locations to protect dwelling sites or gardens, almost always on prominent, raised ground which was then terraced; as for example in the Auckland region, where dormant volcanic cones were used. While built for defense, many were also primarily residential, and often quite extensive.

Māori pā played a significant role in the New Zealand Land Wars, though they are known from earlier periods of Māori history. They were mostly absent, however, until around 500 years ago, suggesting scarcity of resources through environmental damage and population pressure began to bring about warfare, leading to a period of pā building.

Fortification

Their main defense was the use of earth ramparts (or terraced hillsides), topped with stakes or wicker barriers. The historically later versions were constructed by people who were fighting with muskets and hand weapons (such as spear, taiaha and mere) against the British Army and armed constabulary, who were armed with swords, rifles, and heavy weapons such as howitzers and rocket artillery.

Pā were often put in place in very limited time scales, sometimes less than two days, and resisted attack for many hours and, sometimes, weeks. Military historians like John Keegan have noted that Māori recognition of the strong resistance of earth fortifications against modern weapons (especially artillery) predates the successful defensive use of trenches and sloped earth ramparts in World War I by many decades.

Warrior chiefs like Te Ruki Kawiti realised these properties as a good counter to the greater firepower of the British. With that in mind, they sometimes built pā purposefully to resist the British Empire's forces, like at Ruapekapeka, which was constructed specifically to draw the enemy, instead of protecting a specific site or place of habitation like more traditional pās. At the Battle of Ruapekapeka, the British suffered 45 casualties, against only 30 amongst the Māori. Afterwards, British engineers twice surveyed the fortifications, produced a scale model and tabled the plans in the House of Commons.

The fortifications of such a purpose-built pa included palisades of puriri trunks and split timber, with bundles of protective flax padding, the two lines of palisade covering a firing trench with individual pits, while more defenders could use the second palisade to fire over the heads of the first below. Simple communication trenches or tunnels were also built to connect the various parts, as found at Ohaeawai Pā or Ruapekapeka. The forts could even include underground bunkers, protected by a thick layer of earth over wooden beams, which sheltered the inhabitants during periods of heavy shelling by artillery.

A limiting factor of the Māori fortifications that were not built as set pieces, however, was the need for the people inhabiting them to leave frequently to cultivate areas for food, or to gather it from the wilderness. Consequently, pā would often be abandoned for 4 to 6 months of each year.

Examples

The old pā remains found on Maungakiekie/One Tree Hill, New Zealand, close to the center of Auckland, represent one of the largest known sites as well as one of the largest pre-historic earthworks fortifications known worldwide.

The word pā can refer to any Māori village or defensive settlement, but often refers to hill forts – fortified settlements with palisades and defensive terraces – and also to fortified villages. Pā are mainly in the North Island of New Zealand, north of Lake Taupo. Over 5000 sites have been located, photographed and examined although few have been subject to detailed analysis.

For more details, start with article.

References

- Māori Kites

- Tangihanga procedures

- Maori Symbolism

- Tikanga Māori, by Sidney M. Mead, Hirini Moko Mead

- Adventist Connect - Education History

- May the People Live, by Raeburn Lange.