AY Honors/Seeds

| Seeds | |

|---|---|

| Nature | |

Skill Level 123 | |

Approval authority General Conference | Year of Introduction 1961 |

See also | |

The most challenging requirement of this honor is probably this:

9. Make a collection of 30 different kinds of seeds, of which only 10 may be collected from commercial seed packages, the other 20 you are to collect yourself. Label each kind as follows: seed name, date collected, location collected, and collector’s name.

1. What is the main purpose of a seed?

2. What foods were first given to man in the Garden of Eden?

3. Identify from a seed or drawing and know the purpose of each of these parts of a seed: seed coat, cotyledon, embryo.

4. List from memory four different methods by which seeds are scattered. Name three kinds of plants whose seeds are scattered by each method.

5. List from memory ten kinds of seeds that we use for food.

6. List from memory five kinds of seeds that are used as sources of oil.

7. List from memory five kinds of seeds that are used for spices.

8. What conditions are necessary for a seed to sprout?

9. Make a collection of 30 different kinds of seeds, of which only 10 may be collected from commercial seed packages, the other 20 you are to collect yourself. Label each kind as follows: seed name, date collected, location collected, and collector’s name.

1

The main purpose of a seed is to grow a new plant, thus propagating the species.

2

Then God said, "I give you every seed-bearing plant on the face of the whole earth and every tree that has fruit with seed in it. They will be yours for food. Genesis 1:29

3

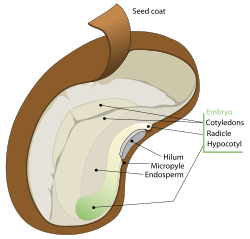

- Seed Coat - The seed coat is the covering which encloses the seed (small embryonic plant, usually with some stored food).

- Cotyledon - This is a significant part of the embryo within the seed of a plant. Upon germination, the cotyledon becomes the embryonic first leaves of a seedling.

- Embryo - A seed embryo includes the cotyledon which becomes the plant's first leaves, the epicotyl (not shown), which becomes the shoot above the leaves, the hypocotyl which becomes the plant's stem, and the radicle which becomes the plant's root.

4

Gravity

The effect of gravity on the dispersal of seeds and spores is straightforward. Heavier seeds will tend to drop downward from the parent plant, and not by themselves travel very far. Spores, being much lighter, are more influenced by physical movements in the environment, especially those of wind and water, and therefore less strictly subject to the simple motion of gravity (see examples below). Gravity may be sufficient agent for plants growing on steep slopes, but upslope movement of a population can be a problem. The naked seeds of gymnosperms are largely dependent upon gravity for dispersal. Most conifers are long-lived large shrubs or tall trees, thus taking full advantage of gravitational dispersal and allowing for gradual upslope movement of a population. Dispersal of seeds "strictly" by gravity should not overlook storm effects: seeds from a deteriorating cone growing high on a tall, narrow tree will get spread widely during a wind storm (see "Wind" below).

Encasing seeds in a rounded fruit promotes gravity driven movement away from the parent.

- Pine trees

- Spruce trees

- Fir trees

- Junipers

- Cedars

- Hemlocks

Mechanical dispersal

Numerous species have mechanical means to overcome the tendency of a seed to drop close to its parent. Seedpods are often shaped so that the seeds are flung away from the parent plant with considerable force as the seedpod matures

Examples of fruit with mechanical dispersal mechanisms:

- Yellow wood sorrel and Touch-me-not – as the seed dries, becomes sensitive to disturbance, ejecting tiny seeds in an explosive discharge. Touch-me-not is named for this behavior.

- Maple trees - the seeds of the Maple tree are those little "helicopters" that children love to play with. As the seeds falls, the wings cause it to rotate, slowing its descent, and thus allowing a breeze to carry it farther from the parent. When the seed strikes the ground, it bores into the soil.

Wind

For non-aquatic, terrestrial plants, the wind is an obvious supplier of energy for movement, and many plants clearly take advantage of this fact. This type of seed dispersal is not efficient, but very effective. Perhaps most familiar are the feather-light fiber parachutes with attached achenes that are produced by a number of species of flowers, a well-known example being the dandelion (see right).

- Milkweed

- Thistles

- Dandelions

Water

Plants that grow in water (aquatic and obligate wetland species) are likely to utilize water to disperse their seeds. For example, all mangroves disperse their offspring by water. In one mechanism, the seedling separates from the fruit, leaving its cotyledons behind, and—floating horizontally on the water surface—is carried away by tidal or river flow. After a month or two, the propagated seed turns vertical in the water. Once it "feels" bottom or strands, roots start to develop and leaves appear at the upper end.

A mechanism commonly seen in coastal plants are those that promote flotation of the fruit, allowing the seed to be carried away on the tide or ocean currents. Examples would be:

- The coconut produces a large, dry, fiber-filled fruit capable of a long survival adrift at sea.

- Alexandrian laurel or kamani produces a globose fruit that is almost cork-like.

Animals

A significant aspect of plant-animal cooperation involves plants designed to take advantage of animal abilities to move. Some fruit have prickly burrs or spikes that attach themselves to a passing animal's fur or feathers so that the animal will carry them away. Some seeds are contained within a soft fruit that "invites" animals to consume it. These seeds have a tough protective outer-coating so that while the fruit is digested, the seeds will pass through their host's digestive tract intact, and grow wherever they fall. Some seeds are appealing to rodents (such as squirrels) who hoard them in hidden caches, often beneath the surface of the soil, in order to avoid starving during the winter and early spring. Those seeds that are left uneaten have the chance to germinate and grow into a new plant.

Some animals that disperse may also eat the seed.

- Beggarlice

- Cockle burr

- Apple

- Banana

- Strawberry

- Oak (acorns)

5

This list does not include the dozens of seeds used as spices or oil (see below), nor does it include seeds which are incidentally eaten as part of a fruit (strawberry, banana). However, you should accept such answers if they are given.

- Almond

- Barley

- Brazil nut

- Cashew

- Chestnut

- Chickpea (garbanzo)

- Cocoa

- Coconut

- Corn

- Cowpea

- Filbert

- Green bean

- Lentil

- Lima bean

- Macadamia

- Millet

- Mustard

- Navy bean

- Oat

- Pea

- Peanut

- Pecan

- Pine nut

- Pinto bean

- Pistachio

- Pomegranate

- Pumpkin

- Rice

- Rye

- Sesame

- Soybean

- Sunflower

- Walnut

- Wheat

- White bean

6

- Coconut

- Corn

- Cottonseed

- Canola oil (a variety of rapeseed oil)

- Olive

- Palm

- Peanut

- Safflower

- Sesame

- Soybean

- Sunflower

- Rice Bran

7

- Anise

- Caraway

- Cardamom

- Cocoa

- Coriander

- Cumin

- Dill

- Fennel

- Nutmeg

- Mustard

- Vanilla

8

Requirements for seed germination

Seed germination depends on many factors, both internal and external. The most important external factors include: water, oxygen, temperature, and the correct soil conditions. Every variety of seed requires a different set of variables for successful germination. This depends greatly on the individual seed variety and is closely linked to the ecological conditions in the plants' natural habitat.

Water

Germination requires moist conditions. Mature seeds are usually very dry and need to take up significant amounts of water before they can "come back to life." The uptake of water into seeds leads to a marked swelling. The pressure caused by water aids in cracking the seed coat for germination. When seeds are formed, most plants store large amounts of food, such as starch, proteins, or oils, for the embryo inside the seed. When the seed absorbs water, it breaks down these stored food resources and allows the seedling to germinate and grow until it reaches the light. Once the seedling starts growing, it requires a continuous supply of water and nutrients.

Oxygen

Most seeds respond best when water levels are enough to moisten the seeds but not soak them, and when oxygen is readily available. Once the seed coat is cracked, the germinating seedling requires oxygen. If the soil is waterlogged, it might cut off the necessary oxygen supply and prevent the seed from germinating.

Temperature and light

Seeds germinate over a wide range of temperatures, with many preferring temperatures slightly higher than room-temperature. Often, seeds have a set temperature range for sprouting and will not sprout above or below a certain temperature. In addition, some seeds may require exposure to light or to cold temperature to break dormancy before they can germinate. As long as the seed is in its dormant state, it will not germinate even if conditions are favorable. For example, seeds requiring the cold of winter are inhibited from germinating if they never experience frost. Some seeds will only germinate when temperatures reach hundreds of degrees, as during a forest fire. Without fire, they are unable to crack their seed coats. Many seeds in forest settings will not germinate until an opening in the canopy allows then to receive sufficient light for the growing seedling.

Stratification

Seeds must be mature and environmental factors must be favorable before germination can take place. When a mature seed is placed under favorable conditions and fails to germinate, it is said to be dormant. Some seeds will not germinate (begin to grow) until they have been dormant for a while. The length of time plant seeds remain dormant can be reduced or eliminated by a simple seed treatment called stratification. Seeds should be planted promptly after stratification.

Stratification mimics natural processes that weaken the seed coat before germination. In nature, some seeds require particular conditions to germinate, such as the heat of a fire (e.g., many Australian native plants), or soaking in a body of water for a long period of time. Others have to be passed through an animal's digestive tract to weaken the seed coat and enable germination.

9

Seeds are all around you. You can find them in many fruits, such as apples, oranges, pears, grapefruit, tangerines, strawberries, lemons. They are also present in many vegetables, such as cucumber, squash, pumpkin, corn (use popcorn for your collection), and beans of all varieties. Take a stroll through the produce section of a grocery store and buy some of these foods. It is especially fun to try new and unusual fruits and vegetables.

Flowers also make seeds, so you can collect seeds from flowers that you already may have growing in your flower bed or someone else's flower beds (with their permission).

You can also collect various seeds in the wild, including grass seeds, milkweed, acorns (and other nuts), clover, goldenrod, etc.

Once you have exhausted these sources, go to the seed section of a store or a nursery. This should be reserved as a last resort.

References

- Wikipedia articles

- Pages using DynamicPageList3 parser function

- Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Do at home

- AY Honors/Honors with an Advanced Option

- Has insignia image

- AY Honors/Naturalist Master Award/Flora

- AY Honors/Honor landing

- AY Honors/Nature

- AY Honors/Introduced in 1961

- AY Honors/Skill Level 1

- AY Honors/Approved by General Conference