Difference between revisions of "AY Honors/Model Railroad/Answer Key"

m (1 revision from w:Rail transport modelling) |

m (Transwiki:Rail transport modelling moved to AY Honor Model Railroad: transwiki import of w:Rail transport modelling) |

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 03:56, 30 November 2008

Template:Unreferenced Template:Trainstopics

Model railroading (US) or Railway modelling (UK, Australia and Canada) is a hobby in which rail transport systems are modeled at a reduced scale, or ratio. The scale models include rail vehicles (locomotives, rolling stock, streetcars, etc.), tracks, signalling, and scenery (roads, buildings, vehicles, model figures, lights, and natural features such as streams, hills and canyons.)

The earliest forms of model railways are the 'carpet railways' which first appeared in the 1840s. "Electric trains" first appeared around the turn of the 20th century. But these early toys were crude likenesses of real trains. Model trains today are generally far more realistic than the toy trains of yesteryear. Today modellers all over the world create sophisticated model railway / railroad layouts, often recreating real locations and periods in history, to show off their "prototypically accurate" models.

General description

Involvement in the hobby can range from the possession of a train set to spending many hours and large sums of money on a large and exactingly executed model of a railroad and the scenery through which it passes, called a "layout". Hobbyists, called "model railroaders" or "railway modellers", may even maintain models large enough to ride (see Live steam, Ridable miniature railway and Backyard railroad). Railway modellers may find enjoyment in collecting model trains, building a miniature landscape for the trains to pass through, or operating their own railroad, albeit in miniature.

Some older scale models reach very high prices. Template:Fact

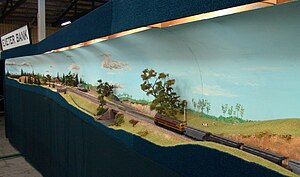

Layouts vary from the very stylistic (sometimes just a simple circle or oval of track) to the "absolutely realistic", where real places are modelled to scale. One of the largest of these is in the Pendon Museum in Oxfordshire, UK, where an EM gauge (same 1:76.2 scale as 00 but with a more accurate track gauge) model of the Vale of White Horse as it appeared in the 1930s is under construction. The museum also houses one of the earliest scenic models ever made - the 'Madder Valley' layout built by John Ahern. This latter layout was built in the late 1930s to late 1950s and brought in the era of realistic modelling, receiving coverage on both sides of the North Atlantic in the magazines Model Railway News and Model Railroader during the 1940s and 50s. Bekonscot in Buckinghamshire is the oldest model village, and also includes a model railway, dating from the 1930s onward. The world's largest model railroad track in H0 scale is Northlandz in Flemington, NJ, United States. The largest live steam layout, with over 25 miles (40 km) of trackage is Train Mountain in Chiloquin, Oregon, U.S..

Model railroad clubs exist where model railway enthusiasts meet. Clubs sometimes put on displays of models for the general public. One rather specialist branch of railway modellers concentrates on larger scales and gauges, most commonly using track gauges from 3.5 to 7.5 inches. Models in these scales are usually hand-built and are powered by live steam, or diesel-hydraulic, and the engines are often powerful enough to haul even dozens of full-scale human passengers. Often model railways of this size are called miniature railways. List of model railroad clubs.

One particularly famous model railway club is the Tech Model Railroad Club (TMRC) at MIT, which in the 1950s pioneered the automatic control of track-switching amongst hobbyists by using advanced technology for the time — telephone relays.

The oldest known society is The Model Railway Club (established in 1910), based near Kings Cross, London, UK. As well as building model railways, they also have a library of in excess of 5000 books, periodicals, etc. Similarly, The Historical Model Railway Society is a Society with its Centre of Excellence at Butterley, near Ripley, Derbyshire. It specialises in Historical railway matters and has considerable archives available to members and non-members alike.

Scales and gauges

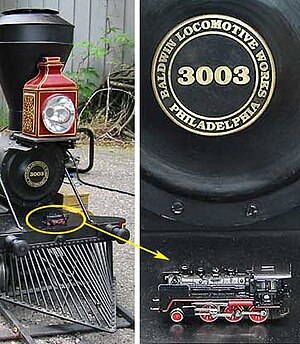

The size of the engines depends on the scale being used and can vary from around 700 mm (28") tall for the largest ridable live steam scales such as 1:8, down to matchbox size for the smallest ones in Z-scale (1:220). A typical HO (1:87) engine is around 50 mm (2") tall, and 100 mm to 300 mm (4" to 12") in length. The six most popular scales used are: G scale, Gauge 1, O scale, H0 scale (in Britain, the similarly sized 00 is used), TT scale, and N scale (1:160), although there is growing interest in Z scale. H0 scale is the single most popular scale of model railroad. Popular narrow-gauge scales include HOn3 Scale and Nn3, which are the same scale as HO and N, except with a narrower spacing between the tracks (in these examples, a scale three feet instead of the 4'8.5" standard gauge).

The largest common scale is 1:8, with 1:4 sometimes used for park rides. G scale (Garden, 1:24 scale) is most popular for back yard modelling. It is easier to fit a G scale model into a garden landscape and still keep the scenery proportional to the size of the trains running through. [Gauge 1] and Gauge 3 are also popular for garden layouts. 0, H0 scale, and N scale are more often used indoors. Lionel trains in 0 scale (1:48 scale) are popular children's toys.

The words scale and gauge seem at first to be used interchangeably in model railways, but their meanings are different. Scale is the model's measurement as a proportion to the original, while gauge is the measurement between the two running rails of the track.

At first, model railways were not to scale. Manufacturers and hobbyists soon arrived at de facto standards for interchangeability, such as gauge, but trains were only a rough approximation to the real thing. See Normen Europäischer Modelleisenbahnen (NEM) and NMRA. Official scales for the various gauges were soon drawn up, but the scales were not at first at all rigidly followed, and were not necessarily correctly proportioned for the rail gauge chosen. O (zero) gauge trains, for instance, operate on track that is too widely spaced in the United States as the scale is accepted as 1:48 where as in Britain 0 gauge use a scale ratio of 43.5:1 or 7 mm/1 foot and the gauge is much near to correct. The British 00 standards operate on track that is significantly too narrow. (The 4 mm/1 foot scale on a 16.5 mm gauge corresponds to a track gauge of 4' 1 1/2", 7 inches under-sized). 16.5 mm gauge corresponds to 4'8.5" standard gauge when modelling in H0 (half zero) 3.5 mm/1 foot or 1:87. Most of the commercial scales also have standards that include wheel flanges that are too deep, wheel treads that are too wide, and rail tracks that are too large.

Later on, groups of modellers became dissatisfied with these inaccuracies, and developed finescale standards in which everything is correctly scaled. These are used by dedicated modellers but have not generally spread to mass-produced equipment in part because the inaccuracies and overscale properties of the commercial scales are necessary to ensure reliable operation in the hands of consumers as well as experts, and also to allow for shortcuts necessary for cost control. These finescale standards include the UK's P4, and the even finer S4, which use a set of track dimensions scaled from the prototype. This 4 mm:1ft modelling uses wheels 2 mm (or less) wide running on track with a gauge of 18.83 mm. Check-rail and wing-rail clearances are similarly accurate.

A compromise of P4 and 00 is 'EM' which uses a gauge of 18.2 mm with much more generous tolerances than P4 for check clearances. It gives a much better appearances than 00 though pointwork is not as close to reality as P4. It suits many people where time and improved appearance are both important.

Landscaping

Some modellers pay special attention to landscaping their model layout, creating either a fantasy world, or closely modelling an actual location, often a historic one, which does not exist anymore. Landscaping is also termed "scenery building" or "scenicking".

Constructing scenery generally involves preparing a sub-terrain using screen wire, a lattice of cardboard strips, or carved stacks of expanded polystyrene (styrofoam) sheets. A scenery base is then applied over the sub-terrain; typical scenery base materials include casting plaster, plaster of Paris, hybrid paper-pulp (papier-mâché) or a lightweight foam/fiberglass/bubblewrap composite as in Geodesic Foam Scenery. The scenery base is covered with ground cover, which may be made from ground foam, colored sawdust, natural lichen, or commercial scatter materials for grass and shrubbery. Buildings and structures can be purchased as kits, or hand fabricated ("scratch built") from cardboard, balsa wood, basswood, paper, or polystyrene or other plastic sheet. Trees can be fabricated from natural materials such as Western sagebrush, candytuft, and caspia, to which an adhesive and model foliage are applied. Water can be simulated using polyester casting resin, polyurethane, or rippled glass. Rocks can be cast in plaster or in plastic with a foam backing. Castings can be painted with stains to give realistic coloring and shadows.

Weathering

Weathering refers to the process of making a model look as if it has been used and exposed to the weather by simulating the natural dirt and wear on real vehicles, structures and equipment. Most models come out of the packet (box) looking new, because unweathered finishes are easier to produce and many collectors want their display models to look pristine. Also, the type of wear an actual freight car or building undergoes will depend not only on its age, but also on where it is used. Rail cars in cities may accumulate grime from higher levels of building and automobile exhaust, while cars that are operated in sandy desert conditions may instead be subjected to sandstorms, which might etch or strip paint prematurely. A model that is weathered, then, would not fit in as many layouts as a pristine model (which can be appropriately weathered by its purchaser).

However, the practice of weathering purchased models, is very common. At the very least, weathering typically aims to reduce the plastic-like finish of scale models. The simulation of grime, rust, dirt, and wear add additional realism. Some modelers may simulate fuel spillage stains on fuel tanks, or corrosion on battery boxes. In some cases, evidence of past accidents or repairs may be added, such as dents or freshly-painted replacement parts, and well-weathered models can be nearly indistinguishable from their prototypes when photographed appropriately.

Methods of power

Model railway engines are generally operated by low voltage DC electricity supplied via the tracks, but there are exceptions, such as Märklin and Lionel Corporation, which use AC.

Most of the early models made for the toy market were powered by clockwork and controlled by stop/go and reverse levers on the locomotive itself. Although this made control crude the models were of large enough scale and robust enough that grabbing the controls as they ran around the track was quite practical. Various manufacturers also introduced slowing and stopping tracks that could trigger levers on the locomotive and allow reliable station stops to be performed. Other locomotives, particularly large models used actual steam. Steam or clockwork driven engines are still sought by collectors.

Early electrical models used a three-rail system with the wheels resting on a metal track with metal sleepers that conducted power and a separate middle rail which provided power to a skid under the locomotive. This at first apparently strange arrangement made sense at the time as the majority of materials used for railway models were metal and conductive. Modern plastics were not yet available and insulation was therefore a significant problem. In addition the notion of accurate models had yet to evolve and toy trains and track were generally crude tinplate representations of generic models.

As model accuracy became more important some model systems adopted two rail power where the wheels were isolated from each other and the two rails carried the positive and negative supply or the two sides of the AC supply. Other model systems such as Märklin instead used a set of fine metal studs to replace the central rail, allowing existing three rail models to use more realistic track.

Although DC power with the positive and negative charges on the two rails is the most common method of power, Märklin and Lionel use AC power on the three rail system. American Flyer is another exception, which used AC power on two-rail track.

Early electric trains ran on battery power, because few homes in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were wired for electric power. Today, inexpensive train sets running on battery power are once again becoming more common, but these are generally regarded as toys and are seldom used by hobbyists. Battery power is also used by many garden railway and larger scale systems both because of the difficulty in obtaining reliable power supply through the rails when outdoors and because the high power consumption and thus current draw of large scale garden models is more easily and more safely met with lead acid batteries.

Engines powered by Live steam are often built in large, outdoor gauges, and are also readily available in Gauge 1, G scale, 16 mm scale and can be found in O and HO scale. Hornby Railways produce a range of live steam locomotives in 00 gauge, development of work by some very dedicated modellers who hand-build live steam models in HO/00, OO9 and N, and there is even one in Z in Australia.

Occasionally the topic of gasoline-electric models, patterned after real-life diesel-electric locomotives, comes up among dedicated hobbyists; and companies like the Pilgrim Locomotive Works have sold such locomotives commercially. Large-scale petrol-mechanical and even petrol-hydraulic models are commercially available but these are unusual and significantly pricier than the more usual electrical power.

Control

The first clockwork (spring-drive) and live steam locomotives simply ran until they ran out of power, with no way for the operator to stop and restart the locomotive or to vary its speed. The advent of electric-powered trains, which first appeared commercially in the 1890s, allowed one to control the train's speed by varying the current, or voltage. As trains began to be powered by transformers and rectifiers more sophisticated throttles appeared, and soon trains powered by AC started containing mechanisms that caused the train to change direction and/or even go into a neutral gear when the operator cycled the power. Trains powered by DC can change direction simply by reversing polarity.

Electric power also permits control by dividing the layout into electrically isolated blocks, where trains can be slowed or stopped by lowering or cutting the power to a block. Dividing a layout into blocks also permitted operators to run more than one train on a layout with much less risk of a fast train catching up with and hitting a slow train. Blocks can also trigger signals or other animated accessories on the layout, adding more realism (or whimsy) to the layout. Three-rail systems will often insulate one of the common rails on a section of track, and use a passing train to complete the circuit and activate an accessory.

Many modern day model railways use digital techniques and are computer controlled. The industry standard command system is called Digital Command Control, or DCC. Some less-common closed proprietary systems also exist.

In the large scales, particularly for garden railways, the use of radio control and DCC in the garden has become popular.

Model railway manufacturers

Famous model railroaders

See list of rail transport modellers.

Layout standards organizations

Several organizations exist to set standardizations for connectability between individual layout sections (commonly called "modules"). This is so several (or hundreds, given enough space and power) people or groups can bring together their own modules, connect them together with as little trouble as possible, and operate their trains. Despite different design and operation philosophies, different organizations have similar goals; standardized ends to facilitate connection with other modules built to the same specifications, standardized electricals, equipment, curve radii.

- NTRAK (Website). Standardized 3-track (heavy operation) mainline with several optional branchlines. Focuses on Standard Gauge, but also has specifications for Narrow Gauge. Due to its popularity, it can be found in regional variations, most notably the Imperial-to-Metric measurement conversions. Tends to be used more for 'unattended display' than 'operation'.

- FREMO (Deutsche English). A European-based organisation focusing on a single-track line, HO Scale. Also sets standards for N Scale modules. Standards are considerably more flexible in module shape than NTRAK, and has expanded over the years to accommodate several scenery variations.

- oNeTRAK (Website). Operationally similar to FREMO, standardises around a single-track mainline, with modules of varying sizes and shapes. Designed with the existing NTRAK spec in mind, is fully compatible with such modules.

- ausTRAK (Website). N Scale, two-track main with hidden third track (can be used as NTRAK's third main, as a return/continuous loop, or hidden yard/siding/on-line storage). Australian scenery and rolling stock modelled in Standard Gauge.

- NMRA ([4]) National Model Railroad Association, the largest organization devoted to the development, promotion, and enjoyment of the hobby of model railroading.

- sTTandard ([5]) Polish TT-scale (1:120) modules organization.

- N-orma ([6]) Polish N-scale (1:160) modules organization

See also

- List of model railroad clubs

- Rail transport modelling scales

- Rail transport modelling standards

- Standard gauge in Model railways

- Track layout possibilities

- Wide gauge in Model railways

Displays and famous layouts

- Clemenceau Heritage Museum, elaborate model railroad display depicts the seven railroads that operated in the Upper Verde Valley of Arizona, 1895-1953

- Expo Narrow Gauge model railway exhibition

- Gorre & Daphetid

- Northlandz

- San Diego Model Railroad Museum

- The Great Train Story exhibit at Museum of Science and Industry (Chicago)

- The Toy Train Depot - A museum dedicated to the history of scale model railroading in Alamogordo, New Mexico

- Bekonscot - The oldest model village in the world, featuring a large model railway network

References

External links

- The National Model Railroad Association, USA - the largest model railroad organization in the world

- The Model Railway Club, UK - the oldest known society in the world - established 1910

- The Model Train Wiki - a comprehensive model railroading source specifically for model railroaders, founded February 2008

- RMweb - UK based model railway articles and discussion

bg:Жп моделизъм cs:Modelová železnice da:Modeltog de:Modelleisenbahn es:Tren eléctrico eo:Makettrajno fr:Modélisme ferroviaire it:Modellismo ferroviario he:דגמי רכבות hu:Modellvasút mk:Железничко моделарство nl:Modeltrein ja:鉄道模型 no:Modelljernbane nn:Modelljarnbane pl:Modelarstwo kolejowe pt:Ferromodelismo ru:Железнодорожный моделизм fi:Pienoisrautatie sv:Modelljärnväg zh:鐵道模型