Difference between revisions of "AY Honors/Pioneering"

DesignerBot (talk | contribs) m (insert nowiki-Tag infront of the honor_landing-Template so there is no paragraph infront of the language selector) |

Jomegat bot (talk | contribs) m (Add honors to Wilderness Master) |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

|insignia=Pioneering_Honor.png | |insignia=Pioneering_Honor.png | ||

|field_trip=required | |field_trip=required | ||

| + | |master1=Wilderness | ||

|overview= | |overview= | ||

|challenge= | |challenge= | ||

Revision as of 03:47, 23 January 2021

| Pioneering | |

|---|---|

| Recreation | |

Skill Level 123 | |

Approval authority General Conference | Year of Introduction 1956 |

See also | |

The most challenging requirement of this honor is probably this:

13. Do one of the following:

- a. Assist in constructing a raft, using lashings. Take a five-mile (8.3 km) trip on a river with this raft.

- b. With an experienced wrangler, participate in a two-day, 15-mile (25 km) horseback trip, carrying all needed supplies on a pack horse you have learned to pack.

- c. With an experienced leader, participate in a two-day, 15-mile (25 km) canoe trip, carrying all needed supplies properly. A short portage should be done.

- d. With an experienced leader, participate in a two-day, 15-mile (25 km) backpack trip, carrying all needed supplies.

1. Describe in writing, orally, or with pictures how the early pioneers met the following basic living needs:

- a. Housing and furnishings

- b. Clothing

- c. Food

- d. Cooking

- e. Warmth and light

- f. Tools and handiwork

- g. Sanitation

- h. Transportation

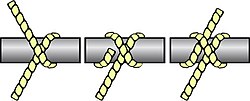

2. Construct a piece of useful furniture by lashing. Learn the following lashings:

- a. Square Lashing

- b. Diagonal Lashing

- c. Shear Lashing

- d. Continuous Lashing

3. Do one of the following:

- a. Weave a basket using natural materials

- b. Make a pair of leather moccasins

- c. Make a lady's bonnet by hand sewing

- d. Make a simple toy used by the pioneers

4. Know how to make flour from at least one wild plant for use in baking.

5. Build a fire without matches. Use natural fire building materials. Keep the fire going for five minutes. You may use the following to start your fire:

- a. Flint and steel

- b. Friction

- c. Electric spark

- d. Curved glass

- e. Metal match

- f. Compressed air

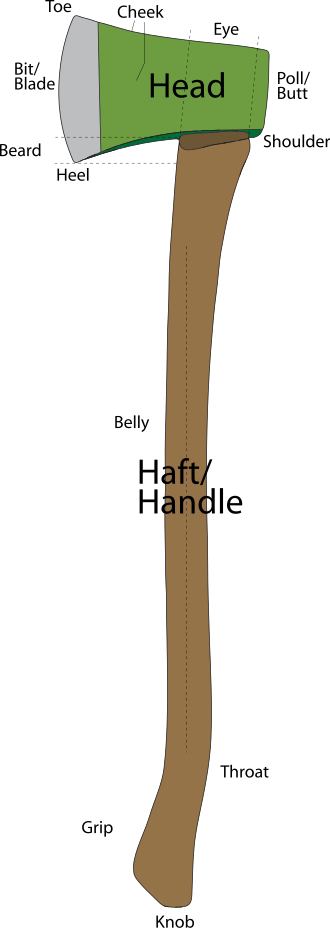

6. Show axmanship knowledge in the following:

- a. Describe the best types of axes.

- b. Show how to sharpen an ax properly.

- c. Know and practice safety rules in the use of an ax.

- d. Know the proper way to use an ax.

- e. Properly cut in two a log at least eight inches (20.3 cm) thick.

- f. Properly split wood that is at least eight inches (20.3 cm) in diameter and one foot (30.5 cm) long.

7. Do two of the following:

- a. Make a ten-foot (3.0 meters) rope from natural material or twine.

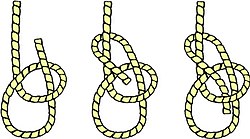

- b. Tie ten knots useful to the pioneer and tell how they were used.

- c. Using rope and natural materials, make one device for moving heavy objects.

- d. Construct an adequate and comfortable latrine.

8. Explain the need for proper sanitation relating to solid and human waste and the washing of body, clothes, and dishes.

9. Assist in the construction of a ten-foot (3.0 meters) long log or rope bridge, using lashings.

10. Know four ways to keep the wilderness beautiful.

11. Do two of the following:

- a. Make a wax candle or other form of pioneer light source

- b. Make a batch of soap

- c. Milk a cow

- d. Churn butter

- e. Make a quill pen and write with it

- f. Make a corn husk doll

- g. Assist in making a quilt

12. Know five home remedies from wild plants and explain their uses.

13. Do one of the following:

- a. Assist in constructing a raft, using lashings. Take a five-mile (8.3 km) trip on a river with this raft.

- b. With an experienced wrangler, participate in a two-day, 15-mile (25 km) horseback trip, carrying all needed supplies on a pack horse you have learned to pack.

- c. With an experienced leader, participate in a two-day, 15-mile (25 km) canoe trip, carrying all needed supplies properly. A short portage should be done.

- d. With an experienced leader, participate in a two-day, 15-mile (25 km) backpack trip, carrying all needed supplies.

1

1a

Housing

The first European settlers in the New World came from England, and brought English building practices with them. In England, timber was scarce, and the building techniques reflected that scarcity. This really made little sense, because the East Coast of the New World where they settled was literally covered with timber. When the Swedes arrived around 1640, they introduced the log cabin. Compared to other house-building techniques, log cabin construction saved a lot of labor. Logs needed to be debarked, cut to length, and notched where they made joints. They did not need to be sawn into planks.

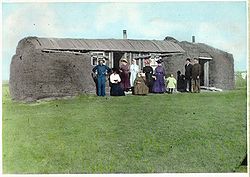

The log cabin served the pioneers well until they pushed into the Great Plains where trees again were scarce. Settlers in the plains turned to the most abundant building material available to them - sod. They would cut from the ground rectangles of sod measuring about 600×300×150mm![]() , and pile them into walls. The resulting structure was a well-insulated but damp dwelling that was very inexpensive. Sod houses required frequent maintenance and were vulnerable to rain damage. Stucco or wood panels often protected the outer walls. Canvas or plaster often lined the interior walls.

, and pile them into walls. The resulting structure was a well-insulated but damp dwelling that was very inexpensive. Sod houses required frequent maintenance and were vulnerable to rain damage. Stucco or wood panels often protected the outer walls. Canvas or plaster often lined the interior walls.

Furnishings

In the early nineteenth century it became increasingly popular for rural Americans of modest means to take the decoration of their homes and furniture into their own hands. Rather than hauling a lot of furniture into newly settled areas, the pioneers frequently made their furnishing at the new homestead site from materials available there.

Rugs could be made from scraps of worn-out clothing or other fabric. Scraps would be braided together to form a long rope, then coiled round and sewn together to form a practical rug.

Barrels and wagon boards might suffice for tables and chairs until proper ones could be built or bought.

Bed supports were made from rope or wooden slats. Mattresses would be filled with straw, corn husks, moss, or other available firm material. Soft upper mattresses could be stuffed with cattail down, wool or feathers.

1b

- Buckskins

- Buckskins are clothing, usually consisting of a jacket and leggings, made from buckskin, a soft sueded leather from the hide of deer or elk. Buckskins are often trimmed with fringe (originally a functional detail, to allow the garment to dry faster when it was soaking wet because the fringe acted as wicks to soak away the water, or quills. Buckskins derive from deerskin clothing worn by Native Americans. They were popular with mountain men and other frontiersmen for their warmth and durability.

- Breeches

- Breeches (pronounced britches) are an item of male clothing covering the body from the waist down, with separate coverings for each leg, usually stopping just below the knee, though in some cases reaching to the ankles. The breeching of a young boy, at an age somewhere between six and eight, was a landmark in his childhood.

- The spelling britches reflects a common pronunciation, and is often used in casual speech to mean trousers or "pants". Breeks is a Scots or northern English spelling and pronunciation.

- Trowsers/Trousers

- These are men's pants or trousers. Often they were made from canvas, wool or linen. The seat was baggy to allow a man to sit down with ease and rode higher than modern pants. Canvas trousers were favored by gold rush men for their sturdiness.

- Shirts

- Men's shirts were often constructed out of squares and rectangles of material so that every inch of fabric was used. Red and blue calico shirts were especially popular because they were not so apt to fade as other colors. White was another popular color because it was easier to clean. Other colors were difficult to keep from fading but a white shirt could easily go back to being white. They were sometimes called "boiled shirts", named for the practice of boiling white shirts to clean them.

- Bonnets

- Sunbonnets were an essential item for pioneers crossing the western trails as a form of 19th century sunscreen. The wide brim and long sides protected their skin from sunburn. Sunbonnet variations (including the slat bonnet and the corded sunbonnet) covered the face, neck and shoulders. In some cases men were even known to wear sunbonnets as protection.

- Hats

- Hats were commonly made from straw, wool felt, or beaver. Most pioneer hats were designed for practicality. A practical pioneer hat would have a wide brim to keep the rain and sun off a man's face.

- Aprons

- An apron is an outer protective garment that covers primarily the front of the body. The apron was traditionally viewed as an essential garment for anyone doing housework because they were so much easier to wash than dresses. Men also wore work aprons to protect their clothes. Cheaper clothes and washing machines made aprons less common beginning in the mid 1960s.

- Dresses

- Dresses were normally made at home from calico or some other inexpensive cloth imported from the east (either the Eastern U.S. or Europe). They could also be made from linsey-woolsey (a sturdy cloth made with a linen warp and a wool weft) which was also called wincey. These wincey dresses were almost indestructible, but not very fashionable. Women with the ability and inclination might also spin and weave their own cloth, called homespun, which they would dye with plants. Wool dresses were prized for their ability to breathe, shed water, stay warm or cool (depending on weave) and the ease of cleaning (most dirt could easily be brushed off), but they did have to be protected from moths and other animals.

1c

The first priority of a pioneer family when arriving in a new area was to build a house and a barn. If possible, they would also set out a garden, however, that depended on their season of arrival. Before crops on a large scale could be planted, land had to be cleared. It was usually not completed during the first year of settling. First the settlers needed to clear the property of trees and stumps. In many areas (notably New England) clearing the trees and stumps would reveal a field full of large rocks which would also have to be cleared. They would build large bon fires over the largest rocks so that the heat would crack them. Then they could extend the fractures by hand to render the boulders into smaller rocks that could be dragged out by horses. The rocks cleared from fields were generally used to construct stone walls along the borders of fields and to mark property boundaries. Clearing fields was a highly laborious process, requiring hours of back-breaking work over an extended period of time.

During the first year of settling, pioneers mostly relied on wild game and their own dehydrated and preserved provisions for food. They also gathered wild plants to eat and used their gardens to the extent that they could. In spring they might tap maple trees for syrup. They also kept livestock and poultry to ensure a steady supply of milk, eggs and meat.

1d

The Pioneers cooked over open fires using Dutch Ovens and kettles. If they had one, they would use a Franklin stove (see below).

1e

- Oil lamps

- Oil, gas and kerosene lamps were used, but were not as common as candles. Lamps did give off more light than candles, but required more supplies and hardware to keep maintained.

- Candles

- With candles, a pioneer did not have to worry about spilling lamp fuel, breaking lamps, or replacing wicks and broken chimneys. Candles were cheaper and more portable than lamps. An average, middle-class household in the 1800s used approximately one hundred pounds of candles per year.

- Homemade candles

- Homemade candles were most often made from tallow (a byproduct of beef-fat rendering). Tallow burned quickly, stunk terribly and gave off a lot of smoke, however they were cheap (most rural people had fat from butchering) and offered an emergency source of sustenance. Tallow candles had to be protected from heat because they melted at a mere 100 degrees. Tallow candles could also be purchased. Purchased tallow candles were the least expensive and cost between sixteen and twenty-five cents per pound or two and two and half cents per candle.

- Beeswax candles

- were also made at home, but not nearly as often as tallow. Beeswax was more expensive, but gave off a nice smell, lasted longer (did not melt until 155 degrees) and did not smoke. A family would more often purchase beeswax candles, but they were by far the most expensive candle. They sold for between sixty and seventy-five cents per pound.

- Stearin

- (a hard, long lasting candle made with stearic acid, a component that hardens fats) and spermaceti (whale oil) candles were always purchased.

- Fireplaces

- A hearth fire was probably the first form of winter heat used by the Pioneers. It not only heated a cabin, it was also used for cooking. However, fireplaces are not very efficient as most of the heat they produce goes right out the chimney. A metal reflector placed in the back of the fireplace helped to alleviate this problem somewhat. Fireplaces also helped to light the home.

- Franklin Stove

- The Franklin stove (named after its inventor, Benjamin Franklin) is a metal-lined fireplace with baffles in the rear to improve the airflow, providing more heat and less smoke than an ordinary open fireplace. It is also known as the circulating stove. Although in current usage the term "stove" implies a closed firebox, the front of a Franklin stove is open to the room.

1f

Tools were an essential element to the pioneers moving into a new area, but they often only brought the most basic ones with them. Among these would be an ax and a drawknife. They first thing they would do with these tools was fashion handles for all their other tools (shovels, hoes, etc.). They usually only brought the metal portions of such tools because the handles were big and bulky, and they had limited cargo-carrying capacity.

1g

Once they arrived in an area, the pioneers would establish a permanent latrine, or an outhouse. This consisted of a hole dug into the ground (three-to-six feet deep). They would then erect a structure over the hole and furnish it with one or two seats positioned over the hole. When the hole was nearly filled with human waste, they would dig another latrine elsewhere and relocated the outhouse over it, burying the old hole with dirt removed from the new one. They did not have toilet paper, but rather used corn cobs, tree bark, leaves, or if they were lucky, the pages from catalogs. Toilet paper became available in 1857 and was sold by the sheet, rather than on a roll but still remained less common than other forms of sanitary wipes.

Wash basins were kept in the bedrooms, and normally, a person would wash their hands and face on a daily basis. Full body bathing was done indoors in a large wash tub. Common advice was to bathe once a week, though some bathed more often and some less. Water was drawn from a well to fill a large metal or wooden wash tub. They would then boil a smaller amount of water in a kettle and add that to the tub as well to warm it up.

Food scraps were fed to animals (cattle, pigs, dogs, etc.).

1h

- Trails

- When the pioneers arrived in the New World, there were no roads at all. There were trails, but these were made for horses and for people on foot, so they were not suited for wagons. Pioneers often widened these footpaths to create trails wide enough for wheeled vehicles to pass.

- Roads

- Rough, quickly built roads, called corduroy roads, were built by felling logs and laying them side-by-side across the "road" and then covering them with earth. This was done in boggy or swampy areas that were otherwise impassable by wagon. After a heavy rain, the earth would be washed away leaving dangerous gaps between the logs. It was not uncommon for a horse to step into one of these gaps and break its leg.

- Wagon Trains

- A wagon train consists of a group of wagons moving together. Whereas wagon trains were common in the Old West, in other places of the world different forms of caravans and convoys were often used, such as camel trains in Australia. A wagon train allowed pioneers to travel together for safety. Each wagon train formed their own government and made their own set of rules for wagon train members to follow. Often these wagon trains would be lead by an experienced 'wagon master' who knew the route. The wagon master would set out his rules and a wagon train wishing to follow him would pay him a set sum of money to lead them safely across the plains.

- Often, at night time, wagon trains would form into a circle, to provide a corral for animals and offer some shelter from wind/weather. Today, covered wagon trains are used to give an authentic experience for those desiring to explore the West as it was in the days of the pioneers and other groups traveling before modern vehicles were invented.

- Rivers

- A quick glance at a modern map of the Eastern United States will show you that Interstate 95 runs up the Atlantic seaboard from one major city to the next. Why are these cities there? A closer inspection will reveal that most of these cities are situated on rivers, and usually at the fall line. The fall line is the place on the river where the first waterfalls are met when traveling upstream. Cities were built here because that's as far as the pioneers could travel by river before they had to get out of their boats. Usually they would haul their cargo overland above the falls and load it onto barges so they could continue the trip by river.

- The Sea

- It was often more economical to travel from one city to the next by getting on a ship and sailing down the coast than it was to ride a horse or walk. Travelers from the eastern coast of America wishing to go to the western coast of North America had the option of taking a ship. A traveler could sail to Panama, get off the ship, travel by land across Panama (The canal had not been built yet!) then take another ship to their final destination. Their other option was to take a ship and sail all the way around the southernmost tip of South America, then up to the Sandwich Islands (now called Hawaii) where they would spend the winter before sailing to their final destination.

- In general, emigrating by sea was more expensive than going overland, but offered slightly more comfort.

2

2a

Square lashing is a type of lashing knot used to bind poles together. Large structures can be built with a combination of square and diagonal lashing, with square lashing generally used on load bearing members and diagonal lashing usually applied to cross bracing. If any gap exists between the poles then diagonal lashing should be used.

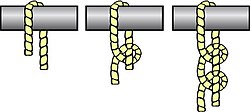

Square lashing steps (see image at right);

- Begin with a timber hitch on the vertical pole beneath the horizontal pole and tuck the loose end under the wrapping.

- Wrap in a square fashion about three times around the poles.

- Frap between the poles two or three times, pulling often to work the joint as tight as possible.

- Tie two half hitches around the horizontal pole

- Cinch the half hitches into a clove hitch, an additional clove hitch may be added if desired.

When the turns are taken around the vertical pole they should be inside the previous turns. The ones around the cross pole should be on the outside of the previous turns. This makes sure that the turns remain parallel and hence the maximum contact between the rope and wood is maintained.

Strength is improved if care is taken to lay the rope wraps and fraps in parallel with a minimum of crossing.

An alternative method is known as the Japanese square lashing. The Japanese square lashing is similar to the standard square lashing in appearance, but in fact is much faster and easier to use. One drawback to consider is that it is difficult to estimate how much rope is needed, which can lead to needlessly long working ends.

- Begin by placing the middle of the rope under the bottom pole

- Lay both ends over the top pole, and cross under the bottom pole. Do this about three times. Take care to keep the wrappings as tight as possible.

- After the last wrap, cross the ropes again over the bottom pole and frap around the wrappings. Do this enough times (at least 3) to finish with a square knot.

A properly executed lashing is very strong and will last as long as the twine or rope maintains its integrity. A lashing stick can be used to safely tighten the joint.

2b

Diagonal lashing is a type of lashing used to bind spars or poles together, to prevent racking. It is usually applied to cross-bracing where the poles do not initially touch, but may by used on any poles that cross each other at a 45° to 90° angle. Large, semipermanent structures may be built with a combination of square lashing, which is stronger, and diagonal lashing.

Bailing twine has sufficient strength for some lashing applications but rope should be used for joining larger poles and where supporting people sized weights.

Diagonal lashing steps (see image at right);

- Begin with a timber hitch around the juncture of the two poles.

- Make three turns in each direction - tightening steadily as you go.

- Make two frapping turns, tightening the joint as much a possible.

- To end, make two half hitches

- Cinch the half hitches into a clove hitch

A lashing stick can be used to safely tighten the joint. Strength will be improved if the first turn is 90° to the timber hitch and if care is taken to lay the rope turns parallel with no crossings.

2c

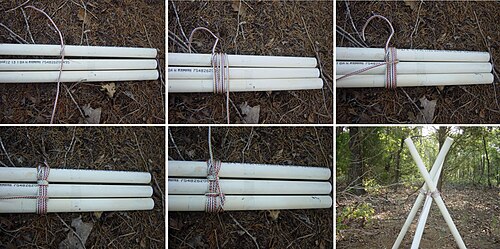

Shear lashing uses two or three spars or poles, 15 - 20 feet of rope.

To tie a shear lashing, lay the two poles side-by-side and parallel to one another. Tie a clove hitch around one spar. Then wrap the free end of the rope around both spars about seven or eight times. Pull them as tight as you can. Then make three fraps around the lashing, and again, pull the rope as tight as you can. Finally, tie a clove hitch on the second spar.

To use sheaer lashing around with three poles, lay all three poles side by side and parallel to one another. Tie a clove hitch on one pole, and wrap the rope around all three seven or eight times. Pull the rope tight. Make three fraps between two of the poles, then cross over and make three more between the other two poles. Pull the frapping as tight as you can and finish it off with a clove hitch.

2d

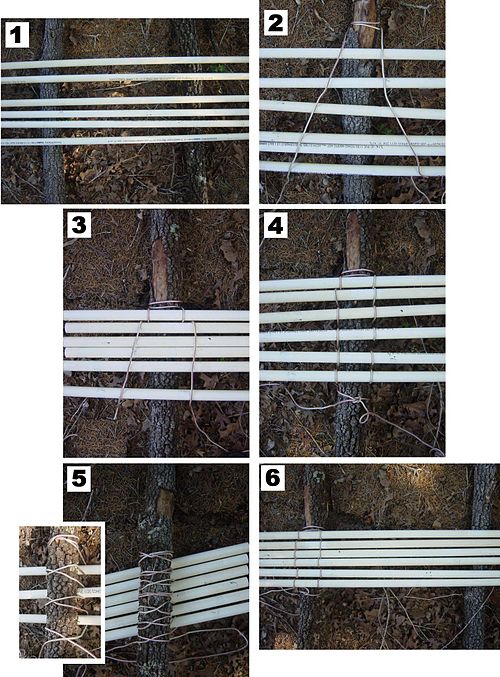

Continuous Lashing is a fun technique. It is used to create shelves, tables, and other structures.

Comments on the pictures on the right'

- Support poles under the 'surface' poles.

- Attach string to the support pole using a clove hitch.

- Clove hitch, up over surface pole, back down & cross under below support pole, and up over the second surface pole.

- Detail of lashing as seen from top.

- Detail of lashing as seen from bottom. Inset shows details of clove hitch, and cross-under below support pole.

- View from the top.

- Start with a string/rope that is 4 or 5 times longer than the length of your project.

- Find the middle/center of the string and attach it to one of the support poles.

- Put one of the surface sticks on top of the support pole and bring both ends of the string over this surface stick.

- Continue back down below the support pole.

- Cross the string under the support pole.

- Bring it back up and over the next surface stick and then back down and cross under the support pole.

- Repeat for the remaining surface sticks.

- End off with a square knot when all the surface sticks are attached.

3

3a

See the Basketry honor for instruction.

3b

Patterns for making moccasins can be found on the Internet, including:

3c

This site has a pattern and instructions for making a slat bonnet. This style, along with its sister style the corded bonnet, was the most popular pioneer style. It was valued for its simplicity and effectiveness. Remember to sew it by hand!

3d

- Corn husk doll

- A corn husk doll could be made by turning a corn husk inside-out and then binding it at the neckline. It was then dressed in miniature clothing.

- Rolled Doll

- This doll is simply made with a square of material of any size, folded in half and rolled up, a few stitches tack the roll of fabric closed, and a few more sew the top closed. Smaller bits of material should be rolled up and tacked to the doll's side to create arms. An original 1831 set of instructions and illustration can be seen in the American Girl's Book.

- Whimmy diddle

- A gee-haw whimmy diddle is mechanical toy consisting of two wooden sticks. One has a series of notches cut transversely along its side and a smaller wooden stick or a propeller attached to the end with a nail or pin. This stick is held stationary in one hand with the notches up, and the other stick is rubbed rapidly back and forth across the notches. This causes the propeller to rotate. Sometimes also known as a "Hooey Stick" or a "VooDoo Stick". The word "Whammy" is sometimes "Whimmy" and the word "Diddle" sometimes "Doodle", giving it a possible 3 other names, and the "Gee-Haw" may also be dropped.

- "Gee-Haw" refers to the fact that, by rubbing your finger against the notched stick while rubbing, the direction of the spinning propeller may be reversed. The operator may do this surreptitiously and yell "Gee" or "Haw" to make it appear that the propeller is reacting the commands. If you call it a "Hooey Stick", you would yell "hooey" each time you want the direction to change.

- Hoop and stick

- A large wooden hoop is rolled along by means of a stick. Skilled players can keep the hoop upright for lengthy periods of time and can do various tricks.

- Whistle

- See the Whistles honor for instruction.

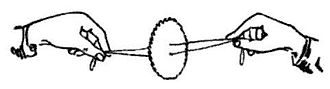

- Buzz Saw/Whirligig/Buzzer

- This is easily made from a large 2 or 4 hole button and a single strand of strong thread or very fine cord. The thread is passed through two button holes (If it is a 4 hole button, use two diagonal holes rather than two holes side by side). Tie a knot in the string.

- To play with the buzz saw, hold and end of the string firmly in each hand so the button falls in the middle, then whip the string around like a jump rope till it is wound tightly. Pull the string so that the button spins, then quickly relax, pull the string again when the button is ready to spin the opposite way. With a little practice you can get a rhythm going and keep the button spinning.(A properly held buzz saw)

4

Flour can be made from clover blossoms. Gather about 8 liters![]() of them and let them dry for two weeks. You can also put them in a low temperature oven for an hour or two. Once they are dry, grind them to powder with a mortar and pestle. This will make about 250 ml

of them and let them dry for two weeks. You can also put them in a low temperature oven for an hour or two. Once they are dry, grind them to powder with a mortar and pestle. This will make about 250 ml![]() of flour. Mix half-and-half with wheat flour. It makes good pancakes.

of flour. Mix half-and-half with wheat flour. It makes good pancakes.

You can also make flour with the roots or pollen of cattail and with acorns. Though acorns may be found in abundance, it is a lot of work to process it into flour. Other nuts (walnuts, hickories, hazelnuts, etc.), though often less abundant, are a little easier to process into flour as they do not require leaching to remove tannin. See the answers to the Edible Wild Plants honor for details.

5

5a

Using flint and steel to light a fire is somewhat difficult. In order to use a flint and steel, you take a hard, sharp-edged rock in one hand and the steel striker in the other. The "flint" can be any hard, sharp rock, such as flint, jasper, or quartz. The striker can be any piece of high-carbon steel, such as a knife blade, though strikers made specifically for this purpose work much better.

The other essential item needed for starting a fire with flint and steel is a char cloth. A char cloth is a piece of partially burned cotton cloth. It can be made by cutting pieces of cotton into 1-inch squares, placing them in small a metal container (such as an Altoids tin), and placing that in a fire. If the cotton cannot get much oxygen, it will char rather than burn. Remove the tin from the fire when it quits smoking.

Before you begin, lay your fire so that when you ignite the tinder with the flint and steel, you can place it in the fire and get it going. Once the tinder is lit, it's too late to lay the fire, as the tinder will burn for only half a minute or so.

Place the char cloth on the flint even with a sharp edge, but not covering it. Hold the striker loosely in the right hand (assuming you are right-handed) and strike it against the flint (held in the other hand) as if you were trying to shave the striker with the rock. Flint is harder than steel, so it will indeed shave a piece of steel off the striker. When this piece of red-hot steel is shaved from the striker, it will fly off and hopefully land on the char cloth. You may need to repeat this several times before a spark does actually land on the char cloth, but when it does, the char cloth will catch the spark and begin to glow itself. You then take the glowing char cloth and set it against your tinder. Raw cotton and oakum work especially well as tinder. Blow on it gently until you get a flame. If you don't blow hard enough, the ember will not ignite the tinder. If you blow too hard, you will burn through the tinder without igniting it. Once it flames up, place it in the fire you have already laid.

5b

The "bow and drill" method is well-known and it is a lot of work. The bow is similar to that used for archery. To make such a bow, find a thin rope or flexible but sturdy bit of cordage, and a sturdy stick 60-120 cm![]() long. Tie the rope to one end of the stick, and make another knot on the other end of the stick, with the rope between the ends not quite taut.

long. Tie the rope to one end of the stick, and make another knot on the other end of the stick, with the rope between the ends not quite taut.

The drill (or spindle) is another straight stick, thin but strong, preferably stripped of bark, sharpened on the bottom end and rounded on the top. The center of the bowstring (rope) is wrapped around the drill, with the bow and spindle at right angles to each other. The end of the spindle is placed on a fireboard.

The fireboard is a piece of dry, softwood (cedar is excellent), with a conical impression in the top surface (such as might be made with a countersink). This impression is bored near the edge of the fireboard, and a notch is cut into it. The apex of the notch should be at the center of the impression. Place a card or a piece of bark beneath the notch to catch the hot wood which the spindle will grind off the fireboard.

The top of the spindle is rounded and smoothed, and placed in a socket made of a hardwood, bone, stone, or something similar. The socket should be smoothed and greased to reduce friction - you do not want to generate heat in the socket.

You should also have a piece of charcloth, which is useful when lighting any kind of primitive. A charcloth is a charred piece of cotton. You can make several by cutting up an old pair of jeans into 2"x1.5" rectangles. Place them in a tin (such as an Altoid tin) with a hole drilled in the top (or bottom). Put the tin (with the cloth inside) into a campfire and carefully remove after about 30 minutes. The tin will prevent the cloth from fully combusting because it limits the oxygen supply. Remove the pieces of cloth and bring them with you when you are ready to light a fire.

Once the equipment is ready, gather some tinder. This tinder should be easily lit. Dry grass, pine needles, and dryer lint all work well for this. Form the tinder pile into the shape of a bird's nest. Then make sure you have enough kindling on hand and an easily lit fire laid with fuel ready to go. When tinder bursts into flames, it is not the right time to start looking for kindling and fuel. Do this ahead of time.

Once the spindle is in place with its bottom tip in the impression in the fireboard, the top held firmly by the socket, and the cord wrapped around its center, the fire builder will move the bow back and forth quickly to rotate the spindle. Long strokes are better than short strokes.

If the socket is pressed too hard, the spindle will not spin. If it is not pressed hard enough, the spindle will come loose.

After only a few seconds of spinning the spindle, the fireboard should begin to smoke. Keep working the bow. After about a minute of smoke, look for a pile of hot wood powder to accumulate in the notch, caught on the card or bark placed beneath it. Stop working the bow and see if the wood powder continues to smoke. If it does not, work the bow again.

When the wood powder continues to smoke after the spindle stops, carefully pick up the card or bark, slide the wood powder into the center of the charcloth, and gently blow on the wood powder. Slowly increase the strength of the air stream blown into the tinder. It should glow red, and as more air is forced into it. In short order, the ember should ignite the charcloth. When it does, slide the charcloth into the tinder and continue blowing. Eventually when you take your next breath, the tinder pile will burst into flames. Place the burning tinder beneath the kindling and tend the fire as you would any newly lit fire.

5c

|

Note: This technique, though listed as an option in the official requirements, was not available to the pioneers. We therefore recommend that it not be used for teaching this honor. |

Making fire from an electric spark can be dangerous and should only be used in an emergency. You will need to set up some tinder ahead of time and then prepare to throw an electrical spark. This can be done with jumper cables from an automobile by connecting one end of the terminals to the battery, and then quickly touch the other ends together next to the tinder. Do not hold the terminals together for more than an instant or you will drain the battery.

5d

A piece of curved glass can sometimes be used to focus the rays of the sun, igniting the tinder. The glass must be smooth enough to not overly-distort the point of light. A magnifying glass is the typical sort of lens used for this, but there are other possibilities in a pinch.

It is possible, for instance, to use a piece of ice shaped into a sphere to do the same job. Getting the piece of ice round enough and, clear enough, and smooth enough to ignite a fire, however may prove to be difficult.

Others have reported success in polishing the bottom of a soda can, and using it as a mirror to reflect the sun's rays onto a point. Again, it takes a lot of patience to polish the can well enough to be able to light a fire this way, but it has been done. The polishing material can be any fine rouge-like substance, such as clay. The surprising thing about this particular technique is that a chocolate bar has been used as the polishing compound!

5e

The term metal match, or 'firesteel' has become synonymous with so called 'artificial flints' which are metal rods of varying size composed of ferrocerium, an alloy of iron and mischmetal. Mischmetal is an alloy primarily of cerium that will generate sparks when struck. Iron is added to improve the strength of the rods. Small shavings are torn off the rod with either a supplied metal scraper, a piece of hacksaw blade, or, commonly, the back of a knife ground at a suitable angle. These shavings then ignite at high temperatures, and they are much more effective than their historical equivalent.

While it takes practice and properly prepared tinder to create a sustained fire, the modern firesteel is considered by survival instructors and serious outdoorspeople to be one of the most reliable ways of making fire in severe conditions. Two good examples of firesteel are made by Light My Fire and Blastmatch. The sparks produced by these products are extremely hot, 3000 C°![]() , and easily light toilet paper or small pieces of wood or commercial tinder products.

, and easily light toilet paper or small pieces of wood or commercial tinder products.

Traditionally a flint and steel were used; however, the flint was not the important part. With a proper striker, you can get sparks using any hard, non-porous rock that has a sharp edge, even petrified wood. The spark comes from chipping small pieces of steel off the striker; finely divided metals ignite immediately in air, with steel burning at yellow-white heat.

Charpaper can be used as an intermediate step between the striking and the tinder. Charpaper is traditionally made from cotton that has been processed into charcoal. You can make charpaper by taking several patches of cotton denim (from an old pair of jeans for example) and laying them one atop another inside a small tin (such as the ones in which Altoids are packaged). Drill a 3 mm![]() diameter hole in the lid of the tin. Then throw it into a campfire. It should smoke, but not ignite, as not enough oxygen can get into the tin. Once it stops smoking, you can carefully remove it from the fire and let it cool. You should have several charpapers inside, ready for the next fire you light.

diameter hole in the lid of the tin. Then throw it into a campfire. It should smoke, but not ignite, as not enough oxygen can get into the tin. Once it stops smoking, you can carefully remove it from the fire and let it cool. You should have several charpapers inside, ready for the next fire you light.

When a spark comes into contact with charpaper, it makes the charpaper glow, but the charpaper will not ignite. After the charpaper glows, you put it against your tender and blow. This works much better than attempting to get a spark to stay on the tinder. Igniting the tinder from the glowing charpaper takes practice. Too much oxygen and the tinder is consumed without bursting into flame; not enough oxygen, and it simply doesn't light. But if you get it just right, it will burst into flames rather suddenly. Be ready for this, as you will then be holding a burning wad of tinder in your hands. Place it in your pre-laid fire immediately.

5f

|

Note: As with the "Electric spark" technique, this method of fire-building was unknown to the pioneers. Again, we recommend against using this option for meeting the requirement. |

In the Pacific Islands near the Philippines, there is a fire building technique that uses compressed air to ignite a small piece of tinder. The technology to do this is similar to a diesel engine and is called a sulpak by the islanders or fire piston by the rest of the world.

The sulpak is usually made out of a water buffalo horn or very dense wood. There are two parts to the device, a piston with a pad on the end, and a cylinder. The piston has a small divot in the end of it that holds a piece of tinder (char cloth works well). Also there is a small groove near the end of the piston that is wrapped with thread to create o-ring. The piston is normally lubricated with pig fat, but Crisco, and Vaseline work well.

The piston is smeared with the lubricant, and a small amount of lubricant is placed in the divot at the end of the piston. The char cloth is then pressed into the grease in the divot.

Push the end of the piston into the cylinder about a half inch. Then hold the cylinder in one hand and hit the pad of the piston with the other. Then pull the piston back out quickly and blow on the tinder. If it doesn't glow immediately you will need to try the process again, or check to make sure that the "o-ring" is tight enough.

There is not enough tinder to catch much on fire, so the best thing to do is light a larger chunk of char cloth and then use this to light the other tinder that will be part of the fire.

It is very difficult to manufacturer the sulpak in the wilderness, so this technique is not good for an emergency unless you just happen to have a sulpak with you. Many outdoor wilderness adventurers will carry their sulpak with them when they go camping and hiking.

Outdoors Magazine.com has a good article with pictures of how to make and use a fire starting piston.

6

6a

The "best" type of axe depends on what you're trying to do with it.

- Felling axe — Cuts across the grain of wood, as in the felling of trees. In single or double bit (the bit is the cutting edge of the head) forms and many different weights, shapes, handle types and cutting geometries to match the characteristics of the material being cut.

- Splitting Axe — Used to split with the grain of the wood. Splitting axe bits are more wedge shaped. This shape causes the axe to rend the fibres of the wood apart, without having to cut through them, especially if the blow is delivered with a twisting action at impact.

- Broad axe — Used with the grain of the wood in precision splitting. Broad axe bits are chisel-shaped (one flat and one bevelled edge) facilitating more controlled work.

6b

It is best to sharpen an axe by hand rather than using an electric grinder. A grinder will heat the blade and ruin the axe's temper. This will cause the bit to soften making it impossible for the axe to hold a sharp edge during typical use. If the axe is very dull or has visible notches in the blade, start sharpening with a file. The file should be held at an angle and run over the length of the blade. Sharpen both sides until the notches are gone. If the axes just needs a touch-up, you can use a sharpening stone. Wet the stone with water (or if you have an oilstone, with oil). This will cause the filings to "float" away an prevent them from clogging the pores in the stone (making it smoother and thus, less effective at sharpening).

6c

Be sure you have firm footing before swinging an axe or a hatchet, and be sure no one is within six feet of you to the sides or to the rear, and within twelve feet of you towards your front.

Be sure that the arc through which you swing the axe is clear, especially of overhead obstructions such as branches.

Axe heads do occasionally come off at times (2 Kings 6:5), and they are very dangerous when they do. Check that the axe head is tight to the handle before using it, and if you find that it is loose, take steps to correct this.

When handing an axe to another person, offer them the handle. Carry the axe so that if you were to trip, the blade would point away from you. Put the axe in a sheath (if it has one) when it is not in use.

6d

Do not hammer an axe into a piece of wood. An axe is for cutting, and should not be used as a wedge. It should also not be used as a sledge hammer. Practice aiming the axe until you get good at it. When you can hit what you aim at, your use of the axe will be far more efficient. Do not chop into the ground - this practice will quickly dull an axe. Apply a bit of oil to the axe head to prevent rust.

6e

Do not lay the log directly on the ground. Otherwise the axe blows will push the log into the ground. Instead, lay it on another small log (three inches in diameter is good). Strike the log to be cut at the point where it is in contact with the supporting log. Otherwise, the log may flip up and strike you or a bystander. This can cause a serious injury, so be watchful.

Proceed by chopping a "vee" into the log, alternating cuts on the left and on the right. The width of the vee should be equal to the diameter of the log. Once the vee penetrates halfway through the log, turn it over and cut another on the opposite side until the two vees meet.

6f

Unless the log you wish to split has been sawn and has a flat end, it will be very difficult to split it. Steady it on its end, and make sure it can stand on its own. Instruct everyone to clear away from you, and do not swing the axe if anyone is near. Grip the end of the axe handle with both hands, and gently lay the blade of the axe on the top of the log, on the edge nearest where you are standing. Fully extend your arms when you do this, and back up if necessary. Spread your feet apart by about the same distance as your shoulders are wide, and make sure your footing is firm. If you are right-handed, slide your right hand towards the head of the axe as you draw it towards yourself. Take aim, and draw the axe over your head, bringing it down mightily as your right-hand slides down the handle. The right hand should meet the left about the same time the axe strikes the log. Note how the axe strikes the wood farther away from you than where you were resting it at the beginning. This is why you should aim for the edge nearest you. If you overshoot the log, you will bring the handle down on the edge of the log and damage the axe. Do that enough, and you'll need to replace the handle.

When splitting a log, try to divide it into two equal masses. If you try to split off a smaller segment, the split will run out, and the piece you remove will be smaller on one end than on the other.

To split a small piece of wood (less than 10 cm![]() in diameter), place the blade of a hatchet on the end of the log, raise the log and the hatchet together, and bring them down sharply on another log or a rock. When they strike the second log, the hatchet's momentum will drive it into the log. Raise the pair again, and strike repeatedly until the log splits apart. Do not steady the log with one hand and strike it with the other. If you miss the log and hit your hand, you will cause an unnecessary emergency.

in diameter), place the blade of a hatchet on the end of the log, raise the log and the hatchet together, and bring them down sharply on another log or a rock. When they strike the second log, the hatchet's momentum will drive it into the log. Raise the pair again, and strike repeatedly until the log splits apart. Do not steady the log with one hand and strike it with the other. If you miss the log and hit your hand, you will cause an unnecessary emergency.

7

7a

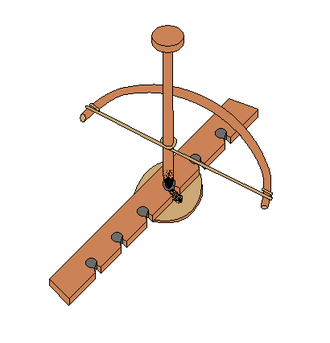

Making rope requires some simple apparatus which you can make yourself easily enough. The first apparatus (we'll call it the twister) is used for twisting three strands of twine (or smaller rope). When making the twister, clamp the two boards that form the handles together tightly and drill three holes through both at the same time. This will ensure that they line up. The hook/crank portion of the twister can be made from coat hanger wire. First make the two 90° bends in the center, then pass them through the holes in the handles. Finally, form the hooks on one end and the other 90° bend on the other. (This final bend prevents the crank from slipping out of the holes in the handle).

As the strands are twisted, they will tend to grab one another and twist together. To make rope, this tendency has to be controlled. This is done with a second apparatus (we'll call it the separator). It consists of a board with three holes drilled in it, forming the points of an equilateral triangle. These points should be at least six inches away from one another, and should be large enough to pass the strands of twine through.

To make rope, cut three pieces of twine about 33% longer than the desired rope. Pass each strand through a hole in the separator, then tie a non-slip loop in the end of each (a figure-eight on a bight works well for this). We will call this end of the strands the free end. Slip these loops over a hook of some sort, and pull the strands straight. Bunch the ends opposite the loops together, and tie them off, again in a loop (and again, a figure-eight on a bight works well for this). We will call this end the bound end. Make sure that the three strands are the same length from one loop to the other. Hand the bound end to a helper, then attach the loops on the free end to the hooks on the twister. Pull the twister away from the bound end (still affixed firmly to another hook) until the strands are straight and tight. Then slide the separator towards the common end. Start cranking the twister so that the hooks rotate. As you crank, your helper will allow the three strands on his side of the separator to twist together. As they do this, the helper will slide the separator towards you, going only as fast as the strands bind to one another. Be careful to keep the strands tight as you do this so that they do not bind to one another on your end of the separator. Continue twisting until the separator reaches the twister. Then tie a knot in the free end of the rope, unhook it from the twister, and slide the separator off. Tie a stopper knot, or bind the end with tape. Then cut off the few inches of untwisted strand that remain (or make a back splice). Finish the opposite end in the same manner. Voilá! You now have a rope!

Guide to making rope from natural materials and no tools. Another technique.

7b

| Bowline |

|---|

|

Use: This knot doesn't jam or slip when tied properly. It can be tied around a person's waist and used to lift him, because the loop will not tighten under load. In sailing, the bowline is used to tie a halyard to a sail head.

How to tie:

|

| Bowline on a bight |

|---|

|

Use: This makes a secure loop in the middle of a rope which does not slip.

How to tie:

|

| Clove hitch |

|---|

|

Use: This knot is the "general utility" hitch for when you need a quick, simple method of fastening a rope around a post, spar or stake (like tying wicks to sticks in Candle Making) or another rope (as in Macramé)

How to tie:

|

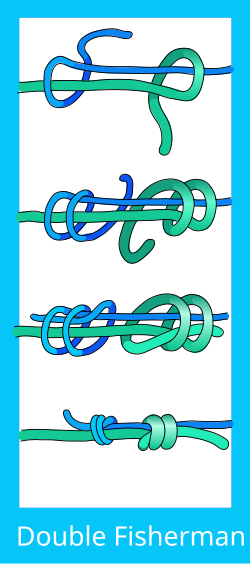

| Double fisherman's knot |

|---|

|

Use: Use the double fisherman's knot to tie together two ropes of unequal sizes. This knot and the triple fisherman's knot are the variations used most often in rock climbing, but other uses include search and rescue.

|

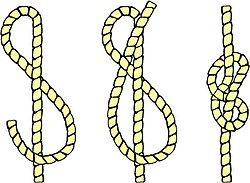

| Figure Eight |

|---|

|

Use: This knot is ideal for keeping the end of a rope from running out of tackle or pulley.

How to tie:

|

| Sheepshank |

|---|

|

Use: The sheepshank knot is used to shorten a length of rope. It comes undone easily unless it is under tension.

WARNING: Keep this knot under tension or it will come untied.

|

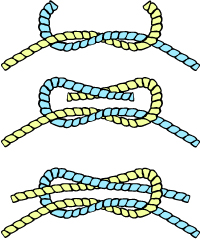

| Square Knot |

|---|

|

Use: Also known as a Reef knot, the Square Knot is easily learned and useful for many situations. It is most commonly used to tie two lines together at the ends. This knot is used at sea in reefing and furling sails. It is used in first aid to tie off a bandage or a sling because the knot lies flat.

How to tie:

WARNING: Do not rely on this knot to hold weight in a life or death situation. It has been known to fail.

|

| Taut-line hitch |

|---|

|

Use: The Taut-Line Hitch is an adjustable loop knot for use on lines under tension. It is useful when the length of a line will need to be periodically adjusted in order to maintain tension. It is made by tying a Rolling hitch around the standing part after passing around an anchor object. Tension is maintained by sliding the hitch to adjust size of the loop, thus changing the effective length of the standing part without retying the knot. When under tension, however, the knot will grip the cord and will be difficult to cause to slip.

It is typically used for securing tent lines in outdoor activities involving camping, by arborists when climbing trees, for creating adjustable moorings in tidal areas, and to secure loads on vehicles. A versatile knot, the Taut-line hitch was even used by astronauts during STS-82, the second Space Shuttle mission to repair the Hubble Space Telescope. How to tie:

|

| Two half hitches |

|---|

|

Use: This reliable knot is quickly tied and is the hitch most often used in mooring.

How to tie:

|

7c

You can make a make-shift block and tackle with nothing more than two sturdy ropes and a tree (or other stationary object). First, take a short length of rope and tie one end around the object you wish to move. Then tie a loop at the other end.

Tie one end of the longer rope around a tree using a bowline. Then tie a slip knot in this rope near the tree. Take the running end of the rope and thread it through the loop you made in the first rope. Then thread it through the slip knot you tied near the tree.

All that remains is to pull on the running end of the longer rope. This setup provides a two-to-one mechanical advantage. For every two meters you pull on the long rope, the object will move one meter closer to the tree.

7d

There are two components to a camping latrine: the "commode", and an enclosure.

- Enclosure

- The purpose of the enclosure is to provide privacy. It can be as simple as hanging tarps from rope stretched between trees and well-secured. You can also make a teepee from tarps and poles, or build a more elaborate structure from poles using lashings, and covering that with tarps. Another possibility is to use an old tent with its floor removed.

- Commode

- There are many ways to build the commode portion of a latrine. One common approach is to mount a toilet seat on some sort of structure, such as a small log cabin-like structure built using 3-inch (8 cm) diameter logs. It is also possible to build a structure from lumber fastened together with hinges so that it can be collapsed at will (but remain uncollapsed otherwise!) for transport. Another way to build the commode is by lashing poles together to make a couple of horizontal rails - one for sitting on, and another as a back rest. However the commode is built, it is almost always situated over a hole dug in the ground to hold the waste. The depth of this hole depends on how much usage the latrine is expected to accommodate. Leave the dirt pile and a shovel inside the enclosure so that the waste may be gradually buried as it is created. This will hold down the smell. Be sure to completely bury the hole when breaking camp.

8

If human waste is not dealt with properly, it can cause disease. It is a small matter for uncontrolled human waste to enter the water supply where it will cause harmful bacteria to multiply. When this happens, anyone using the water internally (i.e., drinking, washing dishes, brushing teeth, etc.) will ingest the bacteria and get sick. Dysentery is a medical condition caused by improper sanitation, and it involves uncontrolled, bloody diarrhea. This causes the body to dehydrate leading to death.

Keeping your body clean is also very important. If you are filthy and you injure yourself, breaking the skin, the filth will readily enter your bloodstream where it can make you sick and cause a painful infection. Infections can kill you if they left untreated.

Dirty clothing can lead to parasitic infestations, such as lice.

Dirty dishes breed bacteria which feast on any food left stuck to the dish. It is then easily transferred to the body when the dish is used for cooking or for eating.

9

Log Bridge

The simplest way to make this bridge is with poles. Cut two long poles at least 15 cm![]() in diameter and long enough to span the item to be bridged. Then cut several smaller poles at least 5cm

in diameter and long enough to span the item to be bridged. Then cut several smaller poles at least 5cm![]() in diameter and approximately 60 cm

in diameter and approximately 60 cm![]() long. Place the long poles over the gap to be spanned such that the short poles can lay across them, overhanging by 3-5cm

long. Place the long poles over the gap to be spanned such that the short poles can lay across them, overhanging by 3-5cm![]() on both sides. Then use continuous lashing to attach the short poles to the long ones. A rope hand rail can be added for additional balance.

on both sides. Then use continuous lashing to attach the short poles to the long ones. A rope hand rail can be added for additional balance.

Rope Bridge

10

- Pick up litter.

- Stay on the trail.

- Use "Leave no Trace" camping techniques.

- Write letters to your elected government representatives about environmental issues.

- Prefer pollution-free recreation activities (biking and hiking over ATV's, canoes and kayaks over motor boats and jet skis, cross country skis over snow mobiles).

- Take only pictures, leave only footprints. That means you don't pick wildflowers or destroy plants. It's generally OK to harvest the fruiting body of a plant (i.e., berries).

- Use a camp stove instead of a campfire when camping. This will eliminate the need to gather firewood and will not leave a fire ring.

11

11a

See the Candlemaking honor for instruction. Why not earn it while you're at it?

11b

Note that this is also a major requirement for the Soap Craft - Advanced honor.

See also the on making soap.

11c

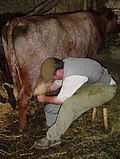

Traditionally the cow, or cows, would stand in the field or paddock while being milked. Young stock, heifers, would have to be trained to remain still to be milked. In many countries the cows were tethered to a post and milked. The problem with this method is that it relies on quiet, tractable beasts, because the hind end of the cow is not restrained. In cold countries where cows are kept in barns, at least for the winter if not throughout the year, they are still tethered only by the neck or head, particularly where they are kept in small numbers.

11d

This can be done when sitting around the campfire. Get a half pint of heavy cream (45% milk fat) and place it in a sealable container with a wide mouth, such as a Tupperware vessel or glass jar with a tight fitting lid. Place a marble (or similar object) in the container with the cream and seal it up tight. (Optional) Then pass it around the campfire having everyone shake it for a minute or two. After ten to fifteen minutes, the container should have two things in it: butter, and buttermilk. You can pour off the buttermilk (save it for biscuits or pancakes in the morning) and you are left with solid butter. The butter solids can then be "washed" by kneading out the pockets of buttermilk with the back of a large spoon. When most of the remaining buttermilk has been worked out, you may salt it to taste and spread it on fresh baked bread. Delicious!

11e

If you don't happen to have a flock of geese from which to pluck feathers, you can always buy them at a craft supply store. Select a feather that is about 30 cm![]() long. The first step in making a quill pen is to temper the shaft. This can be done by heating a tin can filled with sand in an oven at 175°C

long. The first step in making a quill pen is to temper the shaft. This can be done by heating a tin can filled with sand in an oven at 175°C![]() for 15 minutes. If camping, you can do this in a campfire as well. Carefully remove the can from the heat and jam the end of the feather into the sand as far as it will go. Let it sit there until the sand cools. This will cause the transparent shaft of the feather to become opaque.

for 15 minutes. If camping, you can do this in a campfire as well. Carefully remove the can from the heat and jam the end of the feather into the sand as far as it will go. Let it sit there until the sand cools. This will cause the transparent shaft of the feather to become opaque.

Strip some of the "hair" off the feather so that it will not get in the way of the writer's hand. 5 to 7.5 cm![]() will do fine. Hold the feather in your hand to see how it wants to orient itself. Unlike a modern pen, one portion of the feather's shaft will be the "top". Usually, the feather will curve over the hand as you hold it.

will do fine. Hold the feather in your hand to see how it wants to orient itself. Unlike a modern pen, one portion of the feather's shaft will be the "top". Usually, the feather will curve over the hand as you hold it.

This page has a good description, but we'd need to put it in our own words. http://www.flick.com/~liralen/quills/quills.html

11f

For this you will need an ear of corn, still in the husk, a bit twine, and some cloth. Choose one with as much stem attached as you can, up to the intended height of the doll.

Peel the husk back, trying to tear as little of it apart as you can. Fold the husk over the stem. Once all the husk has been folded back, you can chop the corn cob off with a sharp knife. Discard the silks. Tie a piece of twine around the husk an inch or so below the point from which the cob was cut. Tighten it up as much as you can. This will form the neck line. Tie another piece of twine about the middle to form a waist. Then use the cloth to make a dress for the doll (a bonnet conceals the unfortunate fact that your doll is bald). Draw some eyes, a nose, and a mouth on the doll's face using a marker, or for a more authentic look, use a piece of charcoal.

11g

For instruction, see the Quilting honor.

12

|

Warning: We recommend that extreme caution be exercised with regard to these remedies. Some of them are harmless enough (jewelweed, balsam fir, coltsfoot, and garlic), while others are potentially fatal (boneset, feverfew). All medicines are poisonous if the dosage is exceeded, and the amount of the active ingredient found in wild plants is obviously not labeled. |

- Jewelweed

- The juice from this plant was used as a treatment for poison ivy. However, modern medicine has shown that jewelweed is no more effective than a placebo for treating poison ivy.

- Willow

- The bark from the willow tree contains salicylic acid, an ingredient in aspirin. Chewing on willow shoots, twigs, branches, or bark was used as a pain reliever.

- Balsam fir

- The resin of the balsam fir is used to produce Canada balsam, and was traditionally used as a cold remedy.

- Coltsfoot

- The leaves of the coltsfoot plant were used for making tea or hard candy. Both were used as a cough medicine. Again, modern medicine has shown that this treatment is not efficacious.

- Boneset

- Boneset, although poisonous to humans and grazing livestock, has been used in folk medicine, for instance to excrete excess uric acid which causes gout. It has many more presumed beneficial uses, including treatment of dengue fever, arthritis, certain infectious diseases, migraine, intestinal worms, malaria, and diarrhea. Boneset infusions are also considered an excellent remedy for influenza. Scientific research of these applications is rudimentary at present, however. Caution is advised when using boneset, since it contains toxic compounds that can cause liver damage. Side effects include muscular tremors, weakness, and constipation; overdoses may be deadly.

- Feverfew

- Feverfew has been used for reducing fever, for treating headaches, arthritis and digestive problems.

- Garlic

- Garlic has been used as both food and medicine in many cultures for thousands of years, dating at least as far back as the time that the Egyptian pyramids were built. Garlic is claimed to help prevent heart disease including atherosclerosis, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, and cancer.

13

13a

The greatest problem you will need to overcome when building a raft from logs is that logs are very close to having neutral buoyancy, meaning that they do float, but only barely. To deal with this, you will need a great many number of logs.

Gather about 20 logs that are about 3-4 inches (8-10 cm) in diameter, and 16-20 feet (5-6 meters) long. Dry logs are better because they are lighter, and thus have greater buoyancy. You will build the raft upside-down, and then flip it over into the water. It will be very heavy (weighing literally as much as 20 or so logs), so you will want to build it right at the edge of the river.

Lay two of these logs parallel to one another and spaced such that the rest of the logs can lay on top of them perpendicularly. These are the "base" logs. Then lay all but two of the remaining logs on the base logs (and perpendicular to them) in a pile only three feet (3 meters) wide near one end of the base logs. Lash them together as a bundle onto the base logs. Lash the one of the remaining logs to the other end of the base logs, and lash the last one diagonally to prevent racking.

This video should make all the steps fairly clear:

The important point is that the raft gets its flotation from a bundle of logs rather than from a single layer. A single-layer raft will float until someone gets on it. It will still float even with someone on it, but its top surface will be below the water line, making it very difficult to maneuver.

We recommend that the raft be accompanied by other watercraft, such as canoes or john boats. You should also carefully scout the river before committing the raft to it, ensuring there are no rapids.

Because this trip is not an over-nighter, you will be able to use the canoes to carry people instead of gear. Plan on enough canoe capacity to carry everyone in the party just in case the raft is not able to complete the journey (it happens). Assume that each canoe can carry three or four people.

Make sure everyone wears something they can get wet (such as a swimsuit), as well as sandals, river shoes, or old tennis shoes. Personal Floatation Devices (PFDs, also known as life-jackets) are an absolute must, and should be worn at all times while on the water. Under no circumstances should you allow anyone to board the watercraft (especially the raft) without a PFD.

13b

13c

Plan on one canoe for every two people. The supplies should be loaded into the center of the canoe, with the heaviest items being placed lowest in the boat, and the lighter items place on top of them. Remember that the canoe will almost certainly take on a bit of water from wet shoes, dripping paddles, etc., so don't put anything that must stay dry on the bottom of the boat. Some have reported success in placing a tarp down first, loading equipment on top of it, and then drawing the edges over the top of the gear. How ever you load the gear into the canoe, make sure you tie everything down. If the canoe capsizes during the trip, you want the gear to stay with the boat rather than go floating merrily down the stream - or worse - sink to the bottom. Try to remember that this is a possibility when you are selecting your gear. Don't bring anything with you that you cannot afford to leave on a river bottom (such as a borrowed tent, an heirloom axe, or a pair of designer sunglasses). Also try to remember that leaving gear on the bottom of the river is a form of pollution.

Canoe camping has one great advantage over backpacking in that you can pack a lot more gear into a canoe than you can into a backpack. Just don't overdo it. You will still have to carry everything during the portage.

Once the canoe is loaded, check its trim - that is, check that the bow and stern are at the same level. You don't want to have the either end sticking way out of the water, as that will make a canoe "tippy."

Before leading a group down a river, you should scout it first. During your scouting trip, you will be looking for hazards and evaluating river conditions. The trip should answer these questions:

- Are there rapids?

- Is the least skilled person with you able to navigate them?

- Is there an easy way to get off the river upstream from the rapid?

Another important reason to scout the river before bringing the group with you is so that you'll be able to choose the best camping site along the route. When you're going down for the first time, you might be tempted to settle for a sub-optimal site if you don't know there's a better place around the next bend.

13d

Read over the answers in the Backpacking and Hiking honor before setting out. Both have a lot of information that is helpful for a trip like this, and a 15-mile trip will meet the "big" requirement in both.

"Carrying all needed supplies" means that you do not hike from point A to point B while someone else drives an SUV there laden with all your gear.

References

Content on this wiki is generated by people like you, and no one has created a lesson plan for this honor yet. You could do that and make the world a better place.

See AY Honors/Model Lesson Plan if you need ideas for creating one.