Difference between revisions of "Field Guide/Birds/Eastern US and Canada"

m (47 revisions: re-import from WB, including edit history) |

m |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

__TOC__ | __TOC__ | ||

| − | The range maps presented here are color-coded, with yellow indicating the summer range, blue indicating the winter range, and green indicating the year-round range. | + | The range maps presented here are color-coded, with yellow indicating the summer range, blue indicating the winter range, and green indicating the year-round range. Some of the range maps do not follow this color code, but it is not difficult to decode them. |

===Passerine (perching birds)=== | ===Passerine (perching birds)=== | ||

Latest revision as of 04:06, 15 July 2022

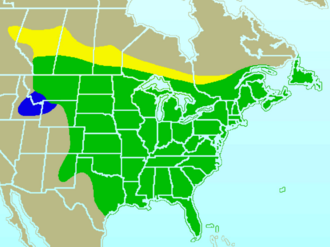

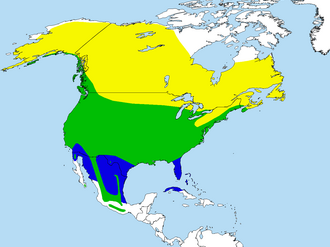

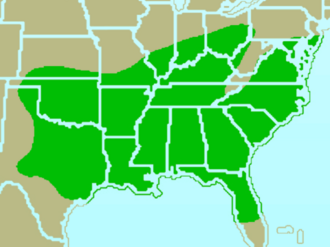

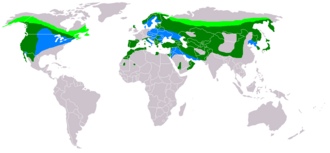

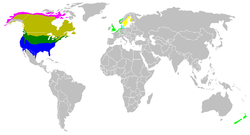

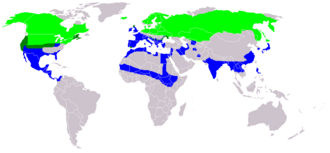

The range maps presented here are color-coded, with yellow indicating the summer range, blue indicating the winter range, and green indicating the year-round range. Some of the range maps do not follow this color code, but it is not difficult to decode them.

Passerine (perching birds)

| Cardinalidae (Cardinal) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| These are robust, seed-eating birds, with strong bills. They are typically associated with open woodland. The sexes usually have distinctive appearances; the family is named for the red plumage (like that of a Catholic cardinal's vestments) of males of the type species, the Northern Cardinal. | |

| Cyanocitta cristata (Blue Jay) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The Blue Jay is a bird with predominantly lavender-blue to mid-blue feathering from the top of the head to midway down the back. There is a pronounced crest on the head. The color changes to black, sky-blue and white barring on the wing primaries and the tail. The bird has an off-white underside, with a black collar around the neck and sides of the head and a white face. Its food is sought both on the ground and in trees and includes virtually all known types of plant and animal sources, such as acorns and beech mast, weed seeds, grain, fruits and other berries, peanuts, bread, meat, eggs and nestlings, small invertebrates of many types, scraps in town parks and bird-table food. | |

| Mimus polyglottos (Northern Mockingbird) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The Northern Mockingbird builds a twig nest in a dense shrub or tree, which it aggressively defends against other birds and animals, including humans. When a predator is persistent, Mockingbirds from neighboring territories, summoned by a distinct call, may join the attack. Other birds may gather to watch as the Mockingbirds harass the intruder. This bird is mainly a permanent resident, but northern birds may move south during harsh weather. Mockingbirds have a strong preference for certain trees such as maple, sweetgum, and sycamore. They generally avoid pine trees after the other trees have grown their leaves. Also, they have a particular preference for high places, such as the topmost branches of trees. Although many species of bird imitate other birds, the Northern Mockingbird is the best known in North America for doing so. It not only imitates birds but also other animals and mechanical sounds. | |

| Turdus migratorius (American Robin) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The American Robin has gray upperparts and head, and orange underparts, usually brighter in the male. Robins are frequently seen running across lawns, picking up earthworms by sight. In fact, the running and stopping behavior is a distinguishing characteristic. When stopping, they are believed to be listening for the movement of prey. | |

| Baeolophus bicolor (Tufted Titmouse) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| These birds have grey upperparts and white underparts with a white face, a grey crest, a dark forehead and a short stout bill; they have rust-colored flanks. The male and female have identical plumage. | |

| Poecile (Chickadee) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| Adults have a black cap and bib with white sides to the face. Their underparts are white with rusty brown on the flanks; their back is grey. They have a short dark bill, short wings and a moderately long tail. There are two types of Chickadee; the Carolina Chickadee, and the Black-capped Chickadee. Carolina Chickadees are so similar to Black-capped Chickadees that they themselves have trouble telling their species apart. Because of this they sometimes mate producing hybrids. The most obvious difference between the three chickadees is that the Carolina Chickadee sings four-note song, Black-capped ones sing two-note songs, and the hybrids sing three-note songs. The song of the Black-capped is a simple, clear whistle of two notes, identical in rhythm, the first roughly a whole-step below the second. This is distinguished from the Carolina chickadee's four-note call fee-bee fee-bay; the lower notes are nearly identical but the higher fee notes are omitted, making the Black-capped song like bee bay. | |

| Sitta carolinensis (White-breasted Nuthatch) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| These birds are permanent residents, sometimes moving south in winter.

They forage on the trunk and large branches of trees, and are well-known for descending head first, a behavior unique to the white-breasted nuthatch. Their principal diet consists of insects and a few varieties of seeds. They often travel with small mixed flocks in winter. | |

| Sialia (Bluebird) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| These are one of the relatively few thrush genera to be restricted to the Americas. As the name implies, these are attractive birds with blue, or blue and red, plumage. Female birds are less brightly colored than males, although color patterns are similar and there is no noticeable difference in size between sexes. There are three species of bluebird; the Eastern Bluebird, the Mountain Bluebird, and the Western Bluebird. The Western Bluebird is very similar to the Eastern Bluebird in appearance. | |

| Agelaius phoeniceus (Red-winged Blackbird) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The Red-winged Blackbird, Agelaius phoeniceus, is a passerine bird found in most of North and much of Central America. It breeds from Alaska and Newfoundland south to Florida, the Gulf of Mexico, Mexico and Guatemala, with isolated populations in western El Salvador, northwestern Honduras and northwestern Costa Rica. It may winter as far north as Pennsylvania and British Columbia, but northern populations are generally bird migration, moving south to Mexico and the southern United States.

The common name for this species is taken from the mainly black adult male's distinctive red shoulder patches, or "epaulets", which are visible when the bird is flying or displaying. At rest, the male also shows a pale yellow wingbar. The female is blackish-brown and paler below. The female is considerably smaller than the male, at 17-18 cm (7 inches) length and 36 g weight, against his 22-24 cm (9.5 inches) and 64 g. Young birds resemble the female, but are paler below and have buff feather fringes. Both sexes have a sharply pointed bill. The Red-winged Blackbird feeds primarily on plant seeds, including weeds and waste grain, but about a quarter of its diet consists of insects, spiders, mollusks and other small animals, considerably more so during breeding season (Srygley & Kingsolver 1998). In season, it eats blueberries, blackberries, and other fruit. These birds can be lured to backyard bird feeders by bread and seed mixtures. When migrating north, these birds travel in single-sex flocks, and the males usually arrive a few days before the females. Once they have reached the location where they plan to breed, the males stake out territories by singing. They defend their territory aggressively, both against other male Red-winged Blackbirds and against birds they perceive as threatening, including crows, Ospreys, hawks, and even humans. The call of this species is a throaty check, and the male's song is scratchy oak-a-lee (see below). Red-winged Blackbirds prefer marshes, but will nest near any body of water. Pairs raise two or three clutches per season, in a new nest for each clutch. The nests are cups of vegetation, and are either built in shrubs or attached to marsh grass. A clutch comprises three to five eggs. These are incubated by the female and hatch in 11-12 days. Red-winged Blackbirds are hatched blind and naked, but are ready to leave the nest ten days after hatching. Red-winged Blackbirds are polygynous, with territorial males defending up to 10 females. However, females frequently copulate with males other than their social mate and often lay clutches of mixed paternity. When the breeding season is over, Red-winged Blackbirds gather in huge flocks, sometimes numbering in the millions. In some parts of the United States, they are considered to be pests because these flocks can consume large amounts of cultivated grain or rice. This bird's numbers are declining due to habitat loss and the use of poison to prevent this loss of crops. Despite the similar names, the Red-winged Blackbird is not related to the European Redwing or the Old World Blackbirdthrushes (Turdidae). | |

| Corvus brachyrhynchos (American Crow) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The American Crowis a common bird found throughout North America. Entirely black, it is an easily recognized bird.

The American Crow is a distinctive bird with iridescent black feathers. Its legs, feet and bill are also black. Several regional forms are recognized and differ in bill proportion and overall size from each other across North America, generally being smallest in the southeast and the far west. Averaging 18 inches (46 cm) in length, it is smaller than the Common Raven. American Crows have a lifespan of 7 to 8 years. Captive birds are known to have lived up to 30 years. The most usual call is a loud, short, and rapid "caah-caah-caah". Usually, the birds thrust their heads up and down as they utter this call. American Crows can also produce a wide variety of sounds and sometimes mimic noises made by other animals, including other birds. Crows live in virtually all types of country from wilderness, farmland, parks, open woodland to towns and major cities. The crow is generally a permanent resident, but many birds in the northern parts of the range migrate short distances southward. Outside of the nesting season, these birds often gather in large communal roosts at night. American Crows are protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. The American Crow is omnivorous. It will feed on invertebrates of all types, carrion, scraps of human food, seeds, eggs and nestlings, stranded fish on the shore and various grains. American Crows are active hunters and will prey on mice, frogs, and other small animals. In winter and autumn, the diet of American Crows is more dependent on nuts and acorns. Occasionally, they will visit bird feeders. Like most crows, they will scavenge at rubbish dumps, scattering garbage in the process. Where available, corn, wheat and other agricultural crops are a favorite food. These habits have historically caused the American Crow to be considered a nuisance. However, it is suspected that the harm to crops is offset by the service the American Crow provides by eating insect pests. American Crows are monogamous cooperative breeding birds. Mated pairs form large families of up to 15 individuals from several breeding seasons that remain together for many years. Offspring from a previous nesting season will usually remain with the family to assist in rearing new nestlings. American Crows do not reach breeding age for at least two years. Most do not leave the nest to breed for four to five years. American Crows build bulky stick nests, nearly always in trees but sometimes also in large bushes and, very rarely, on the ground. They will nest in a wide variety of trees, including large conifers, although oaks are most often used. Three to six eggs are laid and incubated for 18 days. The young are fledged usually by about 35 days. Despite attempts by humans in some areas to drive away or eliminate these birds, they remain widespread and very common. The number of individual American Crows is estimated by Birdlife International to be around 31,000,000. The large population, as well as its vast range, are the reasons why the American Crow is considered to be of least concern, meaning that the species is not at immediate risk. | |

| Quiscalus quiscula (Common Grackle) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The 32 cm Their breeding habitat is open and semi-open areas across North America east of the Rocky Mountains. The nest is a well-concealed cup in dense trees (particularly pine) or shrubs, usually near water; sometimes, they will nest in cavities or in man-made structures. They often nest in colonies, some being quite large. This bird is a permanent resident in much of its range. Northern birds migrate in flocks to the southeastern United States. These birds forage on the ground, in shallow water or in shrubs; they will steal food from other birds. They are omnivorous, eating insects, minnows, frogs, eggs, berries, seeds and grain, even small birds. This bird's song is particularly harsh, especially when these birds, in a flock, are calling. The range of this bird expanded west as forests were cleared. In some areas, they are now considered a pest by farmers because of their large numbers and fondness for grain. | |

| Dumetella carolinensis (Gray Catbird) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The Gray Catbird is a medium-sized perching bird.

Adults are dark gray with a slim, black bill and dark eyes. They have a long dark tail, dark legs and a dark cap; they are rust-colored underneath their tail. Their breeding habitat is semi-open areas with dense, low growth across most of North America. They are found in urban, suburban, and rural habitats. They build a bulky cup nest in a shrub or tree, close to the ground. Eggs are light blue in color, and clutch size ranges from 1-5, with 2-3 eggs most common. Both parents take turns feeding the young birds. They migrate to the southeastern United States, Mexico and Central America. These birds forage on the ground in leaf litter, and love freshly worked earth. Some may even visit a freshly turned garden while the gardener is still present. They mainly eat insects and berries. In the United States, this species receives special legal protections under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. The catbird is named for its cat-like call, but it also mimics the songs of other birds. A catbird's song is easily distinguished from that of the Northern Mockingbird or Brown Thrasher because the mockingbird repeats phrases 3-4 times, and the brown thrasher usually repeats each phrase twice, whereas the catbird sings each phrase only once. The catbird's song is usually described as more raspy and less musical than a mockingbird. The catbird produces a variety of calls, including the familiar ones resembling a cat's meow, as well as an alarm call which resembles the quiet quacking of a male mallard. In contrast to many songbirds which choose a prominent perch from which to sing, the catbird often chooses to sing from inside a bush or small tree, where they are obscured from view by the foliage. The syrinx of gray catbirds has an unusual structure that not only allows them to make mewing sounds like that of a cat but also allows them to imitate other birds, tree frogs, and even mechanical sounds that they hear. Their unusual syrinx also allows them to sing in two voices at once. Gray catbirds are not afraid of predators and respond to them aggressively to them by flashing their wings and tails and by making their signature mew sounds. They are also known to even attack and peck predators that come too near their nests. | |

| Molothrus ater (Brown-headed Cowbird) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| Adults have a short finch-like bill and dark eyes. The adult male is mainly iridescent black with a brown head. The adult female is grey with a pale throat and fine streaking on the underparts.

Breeding in open or semi-open country across most of North America, this bird is a brood parasite: it lays its eggs in the nests of other small perching birds, particularly those that build cup-like nests, such as the Yellow Warbler. The young cowbird is fed by the host parents at the expense of their own young. Brown-headed Cowbirds are permanent residents in the southern parts of their range; northern birds migrate to the southern United States and Mexico. They often travel in flocks, sometimes mixed with Red-winged Blackbirds or European Starlings. These birds forage on the ground, often following grazing animals such as horses and cows to catch insects stirred up by the larger animals. They mainly eat seeds and insects. At one time, the Brown-headed Cowbird followed the bison herds across the prairies. Their parasitic nesting behavior complemented this nomadic lifestyle. Their numbers expanded with the clearing of forested areas and the introduction of new grazing animals by settlers across North America. Brown-headed Cowbirds are now commonly seen at suburban birdfeeders. Brown-headed Cowbird females can lay 36 eggs in a season. Over 140 different species of birds are known to have raised young cowbirds. Host parents may sometimes notice the cowbird egg. Different species react in different ways. Gray Catbirds destroy the egg by pecking it. Some species may simply build a new layer over the bottom of the original nest. Brown-headed cowbird nestlings are sometimes expelled from the nest. | |

Piciformes (woodpeckers)

| Melanerpes erythrocephalus (Red-headed Woodpecker) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The Red-headed Woodpecker, Melanerpes erythrocephalus, is a small or medium-sized woodpecker.

Adults have a black back and tail with a red head and neck. Their underparts are mainly white. The wings are black with white secondaries. Non-birders often mistakenly identify the Red-bellied Woodpecker as this species. Their breeding habitat is open country across southern Canada and the eastern-central United States. They nest in a cavity in a dead tree or a dead part of a tree. Northern birds migrate to the southern parts of the range; southern birds are often permanent residents. These birds fly to catch insects in the air or on the ground, forage on trees or gather and store nuts. They are omnivorous, eating insects, seeds, fruits, berries and nuts. Once abundant, populations have seriously declined since 1966 due to increased nesting competition from starlings and removal of dead trees (used as nesting sites) from woodlands. Many Northeastern states no longer have nesting red-headed woodpeckers. They give a "tchur-tchur" call or drum on territory. To see and hear the Red Headed Woodpecker please click this link, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ic6YPqC2wfU The red-headed woodpecker is listed as a vulnerable species in Canada and as a threatened species in some states in the US. The species has declined in numbers due to habitat loss caused by harvesting of snags, agricultural development, channeling of rivers, a decline in farming resulting to regeneration of eastern forests, monoculture crops, the loss of small orchards, and treatment of telephone poles with creosote. | |

| Melanerpes carolinus (Red-bellied Woodpecker) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The Red-bellied Woodpecker, Melanerpes carolinus, is a medium-sized woodpecker.

Adults are mainly light grey on the face and underparts; they have black and white barred patterns on their back, wings and tail. Adult males have a red cap going from the bill to the nape; females have a red patch on the nape and another above the bill. The reddish tinge on the belly that gives the bird its name is difficult to see in field identification. They are 9 to 10.5 inches long, and have a wingspan of 15 to 18 inches. Their breeding habitat is usually deciduous forests in southern Canada and the northeastern United States, however they may range as far south as Florida and as far west as Texas. They nest in the decayed cavities of dead trees, old stumps, or in live trees that have softer wood such as elms, maples, or willows; both sexes assist in digging nesting cavities. These birds search out insects on tree trunks. They may also catch insects in flight. They are omnivores, eating insects, fruits, nuts and seeds. Red-bellied woodpeckers are noisy birds, and have many varies calls. Calls have been described as sounding like "churr-churr-churr" or "chuf-chuf-chuf" with an alternating "br-r-r-r-t" sound. Males tend to call and drum more frequently than females, but both sexes call. Red-bellied woodpeckers are attracted to noises that resonate. They tap noisily on aluminum roofs, metal guttering and even on cars to attract mates. Their annoying sound can cause dismay to a person who wishes to sleep peacefully at night. | |

| Dryocopus pileatus (Pileated Woodpecker) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The Pileated Woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus) is a very large North American woodpecker.

Adults (40-49 cm long, 250-350 g weight) are mainly black with a red crest and a white line down the sides of the throat. Adult males have a red line from the bill to the throat and red on the front of the crown. In adult females, these are black. They show white on the wings in flight. The only North American birds of similar plumage and size are the Ivory-billed Woodpecker of the Southeastern United States and Cuba, and the related Imperial Woodpecker of Mexico. Both of those species are extremely rare, if not extinct. Their breeding habitat is forested areas with large trees across Canada, the eastern United States and parts of the Pacific coast. They usually excavate large nests in the cavities of dead trees, and often excavates a new home each year, creating habitat for other large cavity nesters. This bird is usually a permanent resident. These birds mainly eat insects (especially beetle larvae and carpenter ants) as well as fruits, berries and nuts. They often chip out large and roughly rectangular holes in trees while searching out insects. The call is a wild laugh, similar to the Northern Flicker. Its drumming can be very loud, often sounding like someone striking a tree with a hammer. This bird favors mature forests, but has adapted to use second-growth stands and heavily wooded parks as well.

| |

Hummingbirds

| Archilochus colubris (Ruby-throated Hummingbird) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The Ruby-throated Hummingbird (Archilochus colubris), is a small hummingbird. It is the most common species of hummingbird that breeds in the eastern half of North America.

The Ruby-Throated Hummingbird is 7-9 cm long with an 8-11 cm wingspan, and weighs 2-6 g. Adults are metallic green above and greyish white below, with near-black wings. Their bill is long, straight and very slender. The adult male has an iridescent ruby red throat patch which may appear black in some lighting, and a dark forked tail. The female has a dark rounded tail with white tips and generally no throat patch, though she may sometimes have a light or whitish throat patch. The male is smaller than the female, and has a slightly shorter beak. A moult of feathers occurs once per year, and begins during the autumn migration. The breeding habitat is throughout most of eastern North America and the Canadian prairies, in deciduous and pine forests and forest edges, orchards, and gardens. The female builds a nest in a protected location in a shrub or tree. The Ruby-throated Hummingbird is migratory, spending most of the winter in Mexico or Central America. Ruby-throated hummingbirds are solitary. Adults of this species typically only come into contact for the purpose of mating, and both males and females of any age aggressively defend feeding locations within his or her territory. The aggressiveness becomes most pronounced in late summer to early fall as they fatten up for migration. They feed frequently while active during the day and when temperatures drop, particularly on cold nights, they may conserve energy by entering hypothermic torpor. The birds feed on nectar from flowers and flowering trees using a long extendable tongue or catch insects on the wing. Due to their small size, they are vulnerable to insect-eating birds and animals.

Females lay two white eggs averaging 12.9 by 8.5 mm | |

Caprimulgiformes

| Caprimulgus vociferus (Whip-poor-will) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The Whip-poor-will or whippoorwill, Caprimulgus vociferus, is a medium-sized (22-27 cm) nightjar, a type of nocturnal bird. The Whip-poor-will is commonly heard within its range, but less often seen. It is named after its call.

Adults have mottled plumage: the upperparts are grey, black and brown; the lower parts are grey and black. They have a very short bill and a black throat. Males have a white patch below the throat and white tips on the outer tail feathers; in the female, these parts are light brown. The Whip-poor-will's breeding habitat is deciduous or mixed woods across southeastern Canada, eastern and southwestern United States, and Central America. They nest on the ground, in shaded locations, among dead leaves, and usually lay two creamy eggs. This bird does not normally flush from the nest unless it is underfoot. Northern birds migrate to the southeastern United States and south to Central America. Central American races are largely resident. These birds forage at night, catching insects in flight. They normally sleep during the day. | |

Galliformes (turkeys, chickens, grouse, quails, and pheasants)

| Colinus virginianus (Bobwhite Quail) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The Bobwhite Quail, Northern Bobwhite, or Virginia Quail, Colinus virginianus, is a ground-dwelling bird native to North America. The name derives from their characteristic call.

The Bobwhite Quail is a member of the group of species known as New World quail. These quail primarily inhabit areas of early successional growth dominated by various species of pine, hardwood, woody, and herbaceous growth. However, quail habitat varies greatly throughout their range which extends from Mexico east to Florida and north into the Upper Midwest and Northeast. Bobwhites are distinguished by a black cap and black stripe behind the eye along the head. The area in between is white on males and yellow-brown on females. The body is brown, speckled in places with black or white on both sexes, and average weight is five to six ounces (145-200 grams). It forms what are known as "coveys", groups of five to 30 birds, during the non-breeding season (roughly October-April). During the breeding season, typically beginning in mid-April, the Bobwhite coveys dissolve. Social pairs are typically formed between individuals of unknown relationship. These social pairings potentially result in the formation of a mate bond and subsequent female fertilization and egg formation. Eggs are laid at a rate of approximately 1 per day, and they hatch after 23 days. Eggs are normally white with a more pointed end than normal chicken eggs. Both males and females can incubate nests, with most nests predominantly incubated by females. If the first clutch of eggs is unsuccessful, a breeding pair (may be the same pair or a different pair as that which led to the previous nesting attempt) will attempt to lay, incubate, and hatch additional clutches. If the clutch is successful, chicks are precocial and will leave the nest approximately 24 hours following hatching. The breeding season continues until mid-October, and successful nesters (females) can potentially lay, incubate, and hatch up to 3 clutches. The Bobwhite's song is a rising, clear whistle, bob-Wight! or bob-bob-White! The call is most often given by males in spring and summertime. | |

| Bonasa umbellus (Ruffed Grouse) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The Ruffed Grouse, Bonasa umbellus, is a medium-sized grouse occurring in forests across Canada and the Appalachian and northern United States including Alaska. They are non-migratory.

Ruffed Grouse have two distinct color phases, grey and red. In the grey phase, adults have a long square brownish tail with barring and a black subterminal band near the end. The head, neck and back are grey-brown; they have a light breast with barring. The ruffs are located on the sides of the neck. These birds also have a "crest" on top of their head, which sometimes lays flat. Both sexes are similarly marked and sized, making them difficult to tell apart, even in hand. The female often has a broken subterminal tail band, while males often have unbroken tail bands. Another fairly accurate method for sexing ruffed grouse involves inspection of the rump feathers. Feathers with a single white dot indicate a female, feathers with more than one white dot indicate that the bird is a male. Ruffed Grouse have never been successfully bred in captivity. These birds forage on the ground or in trees. They are omnivores, eating buds, leaves, berries, seeds, and insects. The male is often heard drumming on a fallen log in spring to attract females for mating. Females nest on the ground, typically laying 6-8 eggs. Grouse spend most of their time on the ground, and when surprised, may explode into flight, beating their wings very loudly. | |

Columbidae (doves and pigeons)

| Columba livia (Rock Pigeon) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The Rock Pigeon (Columba livia), is a member of the bird family Columbidae, doves and pigeons. The bird is also known by the names of feral pigeon or domestic pigeon. In common usage, this bird is often simply referred to as the "pigeon". The species was commonly known as Rock Dove until the British Ornithologists' Union and the American Ornithologists' Union changed the official English name of the bird in their regions to Rock Pigeon.

The Rock Pigeon has a restricted natural resident range in western and southern Europe, North Africa, and into South Asia. Its habitat is natural cliffs, usually on coasts. Its domesticated form, the feral pigeon, has been widely introduced elsewhere, and is common, especially in cities, over much of the world. In Britain, Ireland, and much of its former range, the Rock Pigeon probably only occurs pure in the most remote areas. A Rock Pigeon's life span is anywhere from 3-5 years in the wild to 15 years in captivity, though longer-lived specimens have been reported. The Rock Pigeon is 30-35 cm long with a 62-68 cm wingspan. The white lower back of the pure Rock Pigeon is its best identification character, but the two black bars on its pale grey wings are also distinctive. The tail is margined with white. It is strong and quick on the wing, dashing out from sea caves, flying low over the water, its white rump showing well from above. The head and neck of the mature bird are a darker blue-grey than the back and wings; the lower back is white. The green and lilac or purple patch on the side of the neck is larger than that of the Stock Dove, and the tail is more distinctly banded. Young birds show little luster and are duller. Eye color of the pigeon is generally orange but a few pigeons may have white-grey eyes. The eyelids are orange and are encapsulated in a grey-white eye ring. Feet are red to pink. When circling overhead, the white under wing of the bird becomes conspicuous. In its flight, behavior, and voice, which is more of a dovecot coo than the phrase of the Wood Pigeon, it is a typical pigeon. Although it is a relatively strong flier, it also glides frequently, holding its wings in a very pronounced V shape as it does. Though fields are visited for grain and green food, it is nowhere so plentiful as to be a pest. The nest is usually on a ledge in a cave; it is a slight structure of grass, heather, or seaweed. Like most pigeons it lays two white eggs. The eggs are incubated by both parents for about 18 days. The nestling has pale yellow down and a flesh-coloured bill with a dark band. It is tended and fed on "crop milk" like other doves. The fledging period is 30 days. | |

| Columba oenas (Stock Pigeon) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The Stock Pigeon (Columba oenas) (formerly Stock Dove) is a member of the family Columbidae, doves and pigeons.

In the northern part of its European and western Asiatic range the Stock Pigeon is a migrant, elsewhere it is a well distributed and often plentiful resident. The three western European Columba pigeons, though superficially alike, have very distinctive characters; the Wood Pigeon may at once be told by the white on its neck and wing, but the Rock Pigeon and Stock Pigeons are more alike in size and plumage. The former, however, has a white rump, and two well-marked black bars on the wing, but the rump of the Stock is grey, and the bars are incomplete. The haunts of the Stock Pigeon are in more or less open country, for though it often nests in trees it prefers parklands to thick woods. It is common on coasts where the cliffs provide holes. Its flight is quick, performed by regular beats, with an occasional sharp flick of the wings, characteristic of pigeons in general. It perches well, and in nuptial display walks along a horizontal branch with swelled neck, lowered wings, and fanned tail. During the circling spring flight the wings are smartly cracked like a whiplash. The Stock Pigeon is sociable as well as gregarious, often consorting with Wood Pigeons, though doubtless it is the presence of food which brings them together. Most of its food is vegetable; young shoots and seedlings are favoured, and it will take grain. The short, deep, "grunting" Ooo-uu-ooh call is quite distinct from the modulated cooing notes of the Wood Pigeon; it is loud enough to be described, somewhat fancifully, as "roaring". The nest, though it is seldom that any nest material is used, is usually in a hole in a tree, a crack in a rock face, or in a rabbit burrow, but the bird also nests in ivy, or in the thick growth round the boles of linden trees. | |

| Streptopelia turtur (Turtle Dove) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The Turtle Dove (Streptopelia turtur) is a member of the bird family Columbidae, which includes the doves and pigeons.

It is a migratory species with a western Palearctic range, including Turkey and north Africa, though it is rare in northern Scandinavia and Russia; it winters in southern Africa. In the British Isles, France, and elsewhere in northwestern Europe it is in severe population decline. This is partly because changed farming practices mean that the weed seeds and shoots on which it feeds, are scarcer, and partly due to shooting of birds on migration in Mediterranean countries. Smaller and slighter in build than other doves, the Turtle Dove may be recognized by its browner color, and the black and white striped patch on the side of its neck, but it is its tail that catches the eye when it flies from the observer; it is wedge shaped, with a dark center and white borders and tips. When viewed from below this pattern, owing to the white under tail coverts obscuring the dark bases, is a blackish chevron on a white ground. This is noticeable when the bird stoops to drink, raising its spread tail. The mature bird has the head, neck, flanks, and rump blue grey, and the wings cinnamon, mottled with black. The abdomen and under tail coverts are white. The bill is black, the legs and eyerims are red. The black and white patch on the side of the neck is absent in the browner and duller juvenile bird, which also has the legs brown. The Turtle Dove, one of the latest migrants, rarely appears in Northern Europe before the end of April, returning south again in September. It is a bird of open rather than dense woodlands, and frequently feeds on the ground. It will occasionally nest in large gardens, but is usually extremely timid, probably due to the heavy hunting pressure it faces on migration. The flight is often described as arrowy, but is not remarkably swift. | |

| Leptotila verreauxi (White-tipped Dove) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The White-tipped Dove (Leptotila verreauxi) is a large New World tropical dove. It is a resident breeder from the southernmost Texas in the USA through Mexico and Central America south to western Peru and central Argentina. It also breeds on the offshore islands of northern South America, including Trinidad and Tobago.

The White-tipped Dove inhabits scrub, woodland and forest. It builds a large stick nest in a tree and lays two white eggs. Incubation is about 14 days, and fledging another 15. The White-tipped Dove has an approx. length of 28 cm (11 in) and a weight of 155 g (5½ oz). Adult birds of most races have a grey tinge from the crown to the nape, a pale grey or whitish forehead and a whitish throat. The eye-ring is typically red in most of its range, but blue in most of the Amazon and northern South America. The upperparts and wings are grey-brown, and the underparts are whitish shading to pinkish, dull grey or buff on the chest. The underwing coverts are rufous. The tail is broadly tipped with white, but this is best visible from below or in flight. The bill is black, the legs are red and the iris is yellow. The White-tipped Dove resembles the closely related Grey-fronted Dove, Leptotila rufaxilla, which prefers humid forest habitats. The best distinctions are the greyer forehead and crown, which contrast less with the hindcrown than in the Grey-fronted Dove. In the area of overlap, the White-tipped Dove usually has a blue (not red) eye-ring, but this is not reliable in some parts of Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay and Uruguay, where it typically is red in both species. The White-tipped Dove is usually seen singly or in pairs, and is rather wary. Its flight is fast and direct, with the regular beats and clattering of the wings which are characteristic of pigeons in general. The food of this species is mainly seeds obtained by foraging on the ground, but it will also take insects, including butterflies and moths. The call is a deep hollow ooo-wooooo. | |

Falconiformes (eagles, falcons, and hawks)

The Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), also known as the American Eagle, is a bird of prey found in North America, most recognizable as the national bird of the United States.

The species was on the brink of extinction in the US late in the 20th century, but now has a stable population and is in the process of being removed from the U.S. federal government's list of endangered species.

This eagle gets both its common and scientific names from the distinctive appearance of the adult's head. Bald in the English name refers to the white head feathers, and the scientific name is derived from Haliaeetus, New Latin for "sea eagle," (from the Ancient Greek haliaetos), and leucocephalus, Latinized Ancient Greek for "white head", from leukos ("white") and kephale ("head").

Description and systematics

An immature Bald Eagle has speckled brown plumage, the distinctive white head and body developing 2-3 years later, before sexual maturity. This species is distinguishable from the Golden Eagle in that the latter has feathers which extend down the legs. Also, the immature Bald Eagle has more light feathers in the upper arm area, especially around the 'armpit'.

Adult females have an average wingspan of about 7 feet (2.1 meters); adult males have a wingspan of 6 ft 6 in (2 meters). Adult females weigh approximately 12.8 lb (5.8 kg), males weigh 9 lb (4.1 kg). The smallest specimens are those from Florida, where an adult male may barely exceed 5 lb (2.3 kg) and a wingspan of 6 feet (1.8 meters). The largest are the Alaskan birds, where large females may exceed 15.5 lb (7 kg) and have a wingspan of approximately 8 feet (2.4 meters).

The northern birds are the subspecies washingtoniensis, whereas the southern ones belong to the nominate subspecies leucocephalus. They are separated approximately at latitude 38° N, or roughly the latitude of San Francisco; northern birds reach a bit further south on the Atlantic Coast, where they occur south to the Cape Hatteras area. Audubon's type specimen of "Washington's Eagle" - named in honor of George Washington& - was apparently an exceptionally large bird, such as are more often found in Alaska; these have been proposed as subspecies alascanus or alascensis, but the variation is clinal and follows Bergmann's Rule.

The Bald Eagle forms a species pair with the Eurasian White-tailed Eagle. These diverged from other Sea Eagles at the beginning of the Early Miocene (c. 10 mya) at latest, possibly - if the most ancient fossil record is correctly assigned to this genus - as early as the Early/Middle Oligocene, some 28 mya (Wink et al. 1996&). As in other sea-eagle species pairs, this one consists of a white-headed (the Bald Eagle) and a tan-headed species. They probably diverged in the North Pacific, spreading westwards into Eurasia and eastwards into North America. Like the third northern species, Steller's Sea-eagle, they have yellow talons, beaks and eyes in adults.

Bald Eagles are powerful fliers, and also soar on thermal convection currents.

In the wild, Bald Eagles can live about 20-30 years, and have a maximum life span of approximately 50 years. They generally live longer in captivity; up to 60 years old.

Bald Eagles normally squeak and have a shrill cry, punctuated by grunts. They do not make the "eagle scream" as often shown on the television. What many recognize as the call of this species is actually the call of a Red-tailed Hawk dubbed into the film.

Range, habitat, and restoration

The Bald Eagle's natural range covers most of North America, including most of Canada, all of the continental United States, and northern Mexico. The bird itself is able to live in most of North America's varied habitats from the bayous of Louisiana to the Sonoran desert and the eastern deciduous forests of Quebec and New England. It can be a migratory bird but it also is not unheard of for a nesting pair to overwinter in its breeding area.

Once a common sight in much of the continent, the Bald Eagle was severely affected by the use of the pesticide DDT in the mid-twentieth century. While the pesticide itself was not lethal to the bird, it made an eagle either sterile or unable to lay healthy eggs: the eagle would ingest the chemical through its food and then lay eggs that were too brittle to withstand the weight of a brooding adult. By the 1960s there were fewer than 500 nesting pairs in the 48 contiguous states of the USA.

Currently it is still slowly but steadily recovering its numbers; Organizations like the Fraternal Order of Eagles which carry the Eagle as their emblem, have helped the American Bald Eagle on its recovery, by supporting other groups that rescue and preserve the Eagles and their habitat. The Bald Eagle can be found in growing concentrations throughout the United States and Canada, particularly near large bodies of water. The U.S. state with the largest resident population is Alaska; out of the estimated 70,000 Bald Eagles on Earth, half live there.

Permits are required to keep this species in captivity (e-CFR 1974). As a rule, the Bald Eagle is a poor choice for public shows, being timid, prone to becoming highly stressed, and unpredictable in nature. As remarked above, they can be long-lived in captivity in key demands are met, but do not breed well even under the best conditions. The only Bald Eagle to be born outside North America hatched on May 3, 2006 in Magdeburg Zoo, Germany.

This species has occurred as a vagrant once in Ireland. The exhausted specimen was discovered by a national parks worker in a northern heath. Presumably, a storm blew it out to sea, and the bird struggled across the Atlantic Ocean.

Reproduction

Bald Eagles build huge nests out of branches, usually in large trees near water. The nest may stretch as large as eight feet across and weigh up to a ton (907kg). When breeding where there are no trees, the Bald Eagle will nest on the ground.

Eagles that are old enough to breed often return to the area where they were born. An adult looking for a site is likely to select a spot that contains other breeding Bald Eagles.

Bald Eagles are sexually mature at 4 or 5 years old. Eagles produce between one and three eggs per year, but it is rare for all three chicks to successfully fly. Both the male and female take turns sitting on the eggs. The other parent will hunt for food or look for nest material.

Diet

The Bald Eagle's diet is varied, including carrion, fish, smaller birds, rodents, and sometimes food scavenged or stolen from campsites and picnics. Most prey is quite a bit smaller than the eagle, but rare predatory attacks on large birds such as the Snow Goose, the Great Blue Heron or even swans have been recorded. Also, fairly large salmon and trout have been taken as well.

To hunt fish, easily their most important live prey, the eagle swoops down over the water and snatches the fish out of the water with its talons. They eat by holding the fish in one claw and tearing the flesh with the other. Eagles have structures on their toes called spiricules that allow them to grasp fish. Osprey also have this adaptation. Bald Eagles have powerful talons. In one case, an eagle was able to fly off with the 6.8 kg (15 lb) carcass of a Mule Deer fawn.

Sometimes, if the fish is too heavy to lift, the eagle will be dragged into the water. It may swim to safety, but some eagles drown or succumb to hypothermia. Occasionally, Bald Eagles will pirate fish away from Ospreys and usually the smaller raptors will have to give up their prey, a practice known as kleptoparasitism.

National bird of the U.S.

The Bald Eagle is the national bird of the United States of America. It is probably one of the country's most recognizable symbols, and appears on most of its official seals, including the Seal of the President of the United States.

Its national significance dates back to June 20, 1782, when the Continental Congress officially adopted the current design for the Great Seal of the United States including a Bald Eagle grasping arrows and an olive branch with its talons. Some states had earlier did so in 1778.

In 1784, after the end of the Revolutionary War, Benjamin Franklin wrote a famous letter to his daughter from Paris criticizing the choice and suggesting the Wild Turkey's character as a desirable trait:

For my own part I wish the Bald Eagle had not been chosen the Representative of our Country. He is a Bird of bad moral character. He does not get his Living honestly. You may have seen him perched on some dead Tree near the River, where, too lazy to fish for himself, he watches the Labour of the Fishing Hawk; and when that diligent Bird has at length taken a Fish, and is bearing it to his Nest for the Support of his Mate and young Ones, the Bald Eagle pursues him and takes it from him.

With all this Injustice, he is never in good Case but like those among Men who live by Sharping & Robbing he is generally poor and often very lousy. Besides he is a rank Coward: The little King Bird not bigger than a Sparrow attacks him boldly and drives him out of the District. He is therefore by no means a proper Emblem for the brave and honest country of America who have driven all the King birds from our Country...

I am on this account not displeased that the Figure is not known as a Bald Eagle, but looks more like a Turkey. For the Truth the Turkey is in Comparison a much more respectable Bird, and withal a true original Native of America . . . He is besides, though a little vain & silly, a Bird of Courage, and would not hesitate to attack a Grenadier of the British Guards who should presume to invade his Farm Yard with a red Coat on.

Despite Franklin's objections, the Bald Eagle remained the emblem of the United States. It can be found on both national seals and on the back of several coins (including the quarter dollar coin until 1999), with its head oriented towards the olive branch. Between 1916 and 1945, the Presidential Flag showed an eagle facing to its left (the viewer's right), which gave rise to the urban legend that the seal is changed to have the eagle face towards the olive branch in peace, and towards the arrows in wartime.&

Bald Eagles as religious objects

The Bald Eagle is a sacred bird in some North American cultures and its feathers, like those of the Golden Eagle, are central to many religious and spiritual customs amongst Native Americans. Some Native Americans revere eagles as sacred religious objects, including the feathers and other parts and are often compared to the Bible and crucifix (AP 2004).

Eagle feathers are often used in traditional ceremonies and are used to honor noteworthy achievements and qualities such as exceptional leadership and bravery.

Despite modern and historic Native American practices of giving eagle feathers to non-Native Americans and Native American members of other tribes who have been deemed worthy, current eagle feather law stipulates that only individuals of certifiable Native American ancestry enrolled in a federally recognized tribe are legally authorized to obtain Bald or Golden Eagle feathers for religious or spiritual use (AP 2002) Attempts to extend this permitted use have met with resistance from members of federally recognized Native American tribes, who even under the permissive legislation sometimes have to wait for years before a good specimen can be procured for their use (AP 2004).

References

- Associated Press (AP) (2002): Native American gets OK to use eagle feathers in religious practices. Retrieved 2006-NOV-30.

- Associated Press (AP) (2004): Residents fight to use eagle feathers. Retrieved 2006-NOV-30.

- Template:IUCN2006 Database entry includes justification for why this species is of least concern

- Boradiansky, Tina S. (1990): Conflicting Values: The Religious Killing of Federally Protected Wildlife. Retrieved 2006-NOV-30.

- DeMeo, Antonia M. (1995): Access to Eagles and Eagle Parts: Environmental Protection v. Native American Free Exercise of Religion. Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly 22(3): 771-813. HTML fulltext

- Electronic Code of Federal Regulations (e-CFR) (1974): Title 50: Wildlife and Fisheries. Part 22 - Eagle Permits. HTML fulltext

- Wink, M.; Heidrich, P. & Fentzloff, C. (1996): A mtDNA phylogeny of sea eagles (genus Haliaeetus) based on nucleotide sequences of the cytochrome b gene. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 24: 783-791. Template:DOI PDF fulltext

Footnotes

- ↑ As explicitly stated by Audubon. However, the subspecific name he chose - washingtoniensis - means properly "from Washington (state)". There has been considerable confusion, with some authors changing it to washingtoni, "(George) Washington's", but the form as originally written is correct.

- ↑ The authors' reservations about using the generalized "2%" rate of molecular evolution have since proven to be well-founded.

- ↑ "http://www.snopes.com/history/american/turnhead.htm". http://www.snopes.com/history/american/turnhead.htm.

External links

- Bald Eagle Info.com. Retrieved 2006-NOV-30.

- BirdHouses101.com: Bald Eagle. Retrieved 2006-NOV-30.

- Cascades Raptor Center. Retrieved 2006-NOV-30.

- GreatSeal.com: The Eagle, Ben Franklin, and the Turkey. Retrieved 2006-NOV-30.

- NE Energy: Barton Island, Massachusetts, Bald Eagle webcam. Retrieved 2006-NOV-30.

- USFWS: 1.24 MB Bald Eagle JPEG. Retrieved 2006-NOV-30.

be:Белагаловы арол cs:Orel bělohlavý da:Hvidhovedet havørn de:Weißkopfseeadler es:Pigargo cabeciblanco eo:Blankkapa maraglo fr:Pygargue à tête blanche it:Haliaeetus leucocephalus he:עיטם לבן ראש nl:Amerikaanse zeearend cr:ᒥᒋᓲ ja:ハクトウワシ pl:Bielik amerykański pt:Águia de cabeça branca sk:Orliak bielohlavý fi:Valkopäämerikotka sv:Vithövdad havsörn ta:வெண்தலைக் கழுகு

| Aquila chrysaetos (Golden Eagle) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) is one of the best known birds of prey in the Northern Hemisphere.

A pair of Golden Eagles remains together for life. They build several eyries within their territory and use them alternately for several years. The nest consists of heavy tree branches, upholstered with grass. Old eyries may be 2 meters The female lays two eggs between January and May (depending on the area). After 45 days the young hatch. They are entirely white and are fed for fifty days before they are able to make their first flight attempts and eat on their own. In most cases only the older chick, which takes most of the food, survives, while the younger one dies without leaving the eyrie. Adult Golden Eagles have an average length of 75-85 cm The plumage colors range from black-brown to dark brown, with a striking golden-buff crown and nape, which give the bird its name. The juveniles resemble the adults, but have a duller more mottled appearance. Also they have a white-banded tail and a white patch at the carpal joint, that gradually disappear with every moult until full adult plumage is reached in the fifth year. Golden Eagles often have a division of labor while hunting: one partner drives the prey to its waiting partner. They have very good eyesight and can spot prey from a long distance. The talons are used for killing and carrying the prey, the beak is used only for eating. The talons of a Golden Eagle are thought to be more powerful than the hand and arm strength of any human being. | |

The Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus), sometimes formerly known in North America as Duck Hawk, is a medium-sized falcon about the size of a large crow: 380-530 millimetres (15-21 in) long. The English and scientific species names mean "wandering falcon", and refer to the fact that some populations are migratory. It has a wingspan of about 1 meter (40 in). Males weigh 570-710 grams; the noticeably larger females weigh 910-1190 grams.

The Peregrine Falcon is the fastest creature on the planet in its hunting dive, the stoop, in which it soars to a great height, then dives steeply at speeds in excess of 320 km/h (200mph)(which beats previous records set by the cheetah and the sail fish) into either wing of its prey, so as not to harm itself on impact. Although not self-propelled speeds, due to the fact that the falcon gathers the momentum and controls its dive, capture (if any) and landing in its own right, technically there is no faster animal. The fastest speed recorded is 390 km/h (242.3mph). At this speed, the air intake is powerful enough to burst the lungs of the bird but the curved cones around its nose divert enough air from the lungs to keep the bird from being injured.

The fledglings practice the roll and the pumping of the wings before they master the actual stoop.

Range, habitat and subspecies

Peregrine Falcons live mostly along mountain ranges, river valleys, coastlines, and increasingly, in cities. They are widespread throughout the entire world and are found in all of the continents except Antarctica.

There are many subspecies of Peregrine Falcons, including:

- Falco peregrinus — the nominate mainly non-migratory race, which breeds over much of western Eurasia

- F.p. anatum — is mostly found in the Rocky Mountains. Although it used to be common throughout eastern North America, and is currently being re-introduced in the region, it remains uncommon in much of its former range. Most mature anatums, except those that breed in more northern areas, winter in their breeding range. It is a rare vagrant to western Europe.

- F. p. brookei — of southern Europe to the Caucasus is smaller and more rufous below that the nominate race.

- F. p. calidus — breeds in the Arctic tundra of Eurasia and is completely migratory and travels as far as sub-Saharan Africa. It is larger and paler than the nominate race.

- F. p. ernesti — is found in New Zealand and is non-migratory

- F. p, macropus — is found in Australia and is non-migratory

- F. p. madens — breeds in the Cape Verde Islands and has brown-washed upperparts.

- F.p. pealei — or Peale's Falcon, is found in the Pacific Northwest of North America, and is non-migratory. Starting from the Puget Sound it dwells along the coast on cliffs and seastacks up the British Columbia coast (including the Queen Charlotte Islands) around the Gulf of Alaska all the way out the Aleutian Islands towards Russia. This subspecies is the largest in the world and preys mostly on Alcids and seaducks.

- F. p. peregrinator — (also called the Shaheen Falcon) has rufous underparts and is a breeding resident in South Asia.

- F. p. tundrius — breeds in the Arctic tundra of North America but is migratory and travels as far as South America.

The Barbary Falcon, Falco (peregrinus) pelegrinoides, is often considered to be a subspecies of the Peregrine.

Peregrines in mild-winter regions are usually permanent residents, and some birds, especially adult males, will remain on the breeding territory. However, the Arctic subspecies migrate; tundrius birds from Alaska, northern Canada and Greenland migrate to Central and South America, and all calidus birds from northern Eurasia move further south or to coasts in winter.

Australian Peregrine Falcons are non-migratory, and their breeding season is from July to November each year.

Behaviour

Peregrine Falcons feed almost exclusively on birds, such as doves, waterfowl and songbirds, but occasionally they hunt small mammals, including bats, rats, voles and rabbits. Insects and reptiles make up a relatively small proportion of their diet. On the other hand, a growing number of city-dwelling Falcons find that feral pigeons and Common Starlings provide plenty of food. Peregrine Falcon also eat their own chicks when starving.

Peregrine Falcons breed at approximately two or three years of age. They mate for life and return to the same nesting spot annually. Their courtship flight includes a mix of aerial acrobatics, precise spirals, and steep dives. The male passes prey it has caught to the female in midair. To make this possible, the female actually flies upside-down to receive the food from the male's talons. Females lay an average clutch of three or four eggs in a scrape, normally on cliff edges or, increasingly, on tall buildings or bridges. They occasionally nest in tree hollows or in the disused nest of other large birds.

The laying date varies according to locality, but is generally:

- from February to March (in the Northern Hemisphere)

- from July to August (in the Southern Hemisphere)

The females incubate the eggs for twenty-nine to thirty-two days at which point the eggs hatch. While the males also sometimes help with the incubation of the eggs, they only do so occasionally and for short periods.

Thirty-five to forty-two days after hatching, the chicks will fledge, but they tend to remain dependent on their parents for a further two months. The tiercel, or male, provides most of the food for himself, the female, and the chicks; the falcon, or female, stays and watches the young.

The average life span of a Peregrine Falcon is approximately eight to ten years, although some have been recorded to live until slightly more than twenty years of age.

Threats

The Peregrine Falcon became endangered because of the overuse of pesticides, during the 1950s and 1960s. Pesticide build-up interfered with reproduction, thinning eggshells and severely restricting the ability of birds to reproduce. The DDT buildup in the falcon's fat tissues would result in less calcium in the eggshells, leading to flimsier, more fragile eggs. In several parts of the world, this species was wiped out by pesticides.

Peregrine eggs and chicks are often targeted by thieves and collectors, so it is normal practice not to publicise unprotected nest locations.

Recovery efforts

Wildlife services around the world organized Peregrine Falcon recovery teams to breed them in captivity.

The birds were fed through a chute, so they could not see the human trainers. Then, when they were old enough, the box was opened. This allowed the bird to test its wings. As the bird got stronger, the food was reduced because the bird could hunt its own food. This procedure is called hacking. To release a captive-bred falcon, the bird was placed in a special box at the top of a tower or cliff ledge.

Worldwide recovery efforts have been remarkably successful. In the United States, the banning of DDT eventually allowed released birds to breed successfully. There are now dozens of breeding pairs of Peregrine Falcons in the northeastern USA and Canada.

Many have settled in large cities, including London Ontario and Derby, where they nest on cathedrals, skyscraper window ledges, and the towers of suspension bridges. About 18 pairs nested in New York City in 2005.[1]

These structures typically closely resemble the natural cliff ledges that the species prefers for nesting locations. During daytime the falcons have been observed swooping down to catch common city birds such as pigeons and Common Starlings. In many cities, the Falcons have been credited with controlling the numbers of such birds, which have often become pests, without resort to more controversial methods such as poisoning or hunting.

In Virginia, state officials working with students from the Center for Conservation Biology of the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg successfully established nesting boxes high atop the George P. Coleman Memorial Bridge on the York River, the Benjamin Harrison Memorial Bridge and Varina-Enon Bridge on the James River, and at other similar locations. Thirteen new chicks were hatched in this Virginia program during a recent year. Over 250 falcons have been released through the Virginia program.

In the 53-mile long New River Gorge of West Virginia, another program is underway to re-establish populations by transferring "bridge chicks" from Virginia, Maryland, and New Jersey to special nesting boxes mounted on the high cliffs. [2]. Chicago also started its habitat protection programs with a special recognition of Peregrine Falcon by making it the official bird of the city.[3]

The Peregrine Falcon was removed from the U.S. Threatened and Endangered Species list on August 25, 1999. In 2003, some states began issuing limited numbers of falconry permits for Peregrines, due to the success of the recovery program.

In the UK, there has been a good recovery of populations since the crash of the 1960s. This has been greatly assisted by conservation and protection work led by the RSPB. Peregrines now breed in many mountainous and coastal areas, especially in the west and north. They are also using some city buildings for nesting, capitalizing on the urban pigeon populations for food

Trivia

- The Mediterranean Peregrine Falcon, in this context known as the Maltese Falcon, was the annual rent required by Holy Roman Emperor Charles V when he donated the Island of Malta to the Knights Hospitaller in 1530.

- The Peregrine Falcon appears on the left hand side of the Coat of arms of the Isle of Man. The Peregrine is used owing to the historical importance of the bird in the Isle of Man. When Henry IV of England gave the Isle of Man to Sir John Stanley he made the condition that Sir John give two Peregrine Falcons to him, and furthermore to every future monarch of England on his or her Coronation Day. This tradition was carried out up to the Coronation of George IV in 1821.

- The air pressure from the Peregrine's bullet-like attack plunge might burst an ordinary bird’s lungs. It’s thought that the series of baffles in a Peregrine’s nostrils slow the wind velocity, enabling the bird to breathe while diving [4]. This feature of the Perigrine's nostrils, once its use was found, was mimicked in fighter jets.

- A Peregrine Falcon, Lucy, was filmed in the movie The Falcon and the Snowman.

- A Peregrine Falcon will be prominently featured on the Idaho quarter to be issued in 2007 as part of the United States Mint's 50 State Quarters program. [5]

- The Peregrine Falcon was declared Chicago's official city bird in 1999 after it began nesting on the city's skyscrapers.

- The Suzuki GSX1300R super-sport motorcycle, aka the Hayabusa (隼), is named after the Japanese word for the Peregrine Falcon. Like the bird, the motorcycle can reach speeds of 300km/h.

References

- Template:IUCN2006 Database entry includes justification for why this species is of least concern

- Tucker VA. Gliding flight: speed and acceleration of ideal falcons during diving and pull out. J. Exp. Biol. 201(Pt 3):403-14 (1998).

Peregrine Falcon webcams

United States

- Utah Peregrine Falcon webcam - real time video of nesting Peregrine Falcons on the Joseph Smith Building in Salt Lake City Utah.

- Woodmen of the World Peregrine Falcon Webcam Webcam for the falcon nest at the Woodmen Tower in downtown Omaha, NE.

- Santa Cruz Predatory Bird Research Group

- San Francisco Peregrine Falcon webcam - Peregrine Falcon webcam on 33rd floor of Pacific Gas and Electric Company building in San Francisco, a SCPBRG site

- Pennsylvania Peregrine Falcon webcam - DEP Falcon Cam shows a nesting pair in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

- Ohio Peregrine Falcon webcam - Falcon Cam showing 16-year-old tiercel "Mercury" and his mate Snowball in Dayton Ohio

- Kodak Birdcam Kodak Birdcam - Kodak Corporate website. Nesting site located at Eastman Kodak Company in Rochester, NY, USA. Five camera views, photo galleries, videos, educational materials for educators and teachers. Tracking falcons Mariah and her mates since 1998

- WPC Peregrine Recovery Program Webcams for the falcon nests at the Gulf Tower and Cathedral of Learning, Pittsburgh, PA.

- Macomb County Peregrine webcam Webcams for the falcon nest at the Macomb County Building in Mount Clemens, MI.

- Indianapolis Star Peregrine Webcam Webcams for the falcon nest at the Key Bank Building in downtown Indianapolis, IN.

- Raptor Resource Project Eight falcon cams, an osprey cam, an owl cam, and an eagle cam. Also includes photo forum, video clips, educational materials, and links.

- Boswell Energy Center Falconcam Webcam for the falcon nest at Minnesota Power's Boswell Energy Center near Cohasset, MN.

Canada

- Peregrine Foundation live cams

- Hamilton Nature Falcon Cam shows chicks in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. Website also features galleries from previous years.

Australia

- FrodoCam Live Peregrine Falcon webcam located in Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. The webcam shows nesting pair, Frodo and his mate Frieda. The website can be accessed all year round, and there is continuous live cam coverage (both day and night) during the Australian breeding season (which lasts from July to November–December each year). There are also photo galleries and video footage from the 2006 breeding season, as well as from previous years, and also a "Frodocam Forum" page. The Australian Peregrine Falcon subspecies is Falco peregrinus macropus, and the nearby New Guinea Peregrine Falcon subspecies is Falco peregrinus ernesti. Both subspecies are non-migratory.

The Netherlands

- Homepage from the Dutch Peregrine Workgroup with timed picture-updates from 13 live cams

- Planet.nl, live video coverage of falcon nest at communication tower in De Mortel, Netherlands

Italy

World cams

- a listing of Bird cams from around the world - site includes direct links to nests with chicks

External links

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology: Peregrine Falcon

- BirdLife Species Factsheet

- US FWS site

- Peregrine Falcon conservation

- Peregrine Foundation, Canada

- picture 20-22 day old Peregrine chicks

- Peregrine Falcons of Morro Rock California

- South Dakota Birds: Peregrine Falcon

bg:Сокол скитник ca:Falcó pelegrí cs:Sokol stěhovavý da:Vandrefalk de:Wanderfalke el:Πετρίτης es:Falco peregrinus eo:Migra falko fr:Faucon pèlerin id:Alap-alap Kawah it:Falco peregrinus lt:Sakalas keleivis mk:Сив сокол nl:Slechtvalk ja:ハヤブサ no:Vandrefalk nn:Vandrefalk pl:Sokół wędrowny pt:Falcão-peregrino ru:Сапсан sk:Sokol sťahovavý sl:Sokol selec sr:Сиви соко fi:Muuttohaukka sv:Pilgrimsfalk ta:வல்லூறு tr:Bayağı doğan uk:Сапсан zh:游隼

| Buteo jamaicensis (Red-tailed Hawk) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) breeds from western Alaska and northern Canada to Panama and the West Indies. Males are typically smaller than females, generally weighing between 800–1100 grams This is one of three species colloquially known in the United States as the "chickenhawk". It is the most common North American hawk and the raptor most frequently taken from the wild (and later returned to the wild) for falconry in the United States. Birds of this species have a dark mark along the leading edge of the underwing, between the body and the wrist. Most, but not all color variations have a dark band across the belly. In most, the adults' tails are rusty red above, and juveniles have narrow brown and pale bands. The main western North American population has bands on the adults' rusty tails as well and has varied plumage, organized into three main color types or morphs. Immature birds, or birds that are only a few years old, can also readily be identified by having yellowish irises. As the bird attains full maturity over the course of 3–4 years, the iris slowly darkens into a reddish-brown hue. The breeding habitat is open country with high perches. They build a stick nest in a large tree, in a cactus, or on a cliff ledge 35 m or higher above ground; they may also nest on man-made structures. Both sexes build the sturdy nest, made of different sized twigs and sticks, lined with fresh green foliage and evergreen sprigs. The fresh sprigs are regularly replaced during incubation. Up to four eggs may be laid at daily intervals. The shells are colored a dull or bluish-white with a granulated or smooth surface, never glossy. There may be some splotches of various shades of brown. Incubation is by the female from 28 to 35 days, during which time she is fed by the male. The young are able to fly at about 45 days. In most of the United States, Red-tailed Hawks are permanent residents, but northern breeding birds migrate south in winter. Throughout their range in the U.S., Red-tailed Hawks receive special legal protections under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. They have a complex relationship with humans, capable of both controlling rodent and other mammalian pests, and on occasion taking valuable fowl (which has led to them being one of the species described as a Chickenhawk). Red-tailed Hawks prefer to wait on a high perch and swoop down on prey; they also patrol open areas in flight. They mainly eat small mammals, birds and reptiles. Their favorite prey varies with regional and seasonal availability but includes most types of rodents, rabbits, pheasant, grouse, quail, rattle snakes, copperheads, lizards, and, when near the water's edge, carp and catfish. Those that live in cities may prefer pigeons and starlings, both of which are plentiful in many urban areas. In flight, these hawks soar with wings in a slight dihedral, flapping as little as possible. They sometimes hover on beating wings and sometimes "kite", or remain stationary above the ground by soaring into the wind. When soaring or flapping their wings, they typically travel from 30 km/h to 65 km/h, but when diving may reach speeds as high as 195 km/h. The Red-tailed Hawk is common and widespread, partly because it has benefited from the historic settlement patterns across North America. The clearing of trees in the east of North America provided hunting areas, and the practice of sparing woodlots left nest sites. Conversely, the planting of trees in the west provided nest sites where there had been none. The construction of highways with treeless medians and shoulders and with utility poles alongside provided perfect habitat for perch-hunting, so Red-tailed Hawks are now a common sight along highways. A certain recording of the cry of the Red-tailed Hawk is probably one of the most often heard cinematic sound clichés. This high, fierce scream is often featured in the background of adventure movies to give a sense of wilderness to the scene. However, the cry is more commonly used for the Bald Eagle, whose own vocalizations are quite different. | |

| Pandion haliaetus (Osprey) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The Osprey, Pandion haliaetus is a medium-large raptor which is a specialist fish-eater with a worldwide distribution. It occurs in all continents except Antarctica, but in South America only as a non-breeding migrant. It is often known by other colloquial names such as fishhawk, seahawk or Fish Eagle.

The Osprey is 52-60 cm Juvenile birds are readily identified by the buff fringes to the upperpart plumage, buff tone to the underparts, and streaked crown. By spring, wear on the upperparts makes barring on the underwings and flight feathers a better indicator of young birds. Adult males can be distinguished from females from their slimmer bodies and narrower wings. They also have a weaker or non-existent breast band than the female, and more uniformly pale underwing coverts. It is straightforward to sex a breeding pair, but harder with individual birds. In flight, Ospreys have arched wings and drooping "hands", giving them a diagnostic gull-like appearance. The call is a series of sharp whistles, cheep, cheep, or yewk, yewk. Near the nest, a frenzied cheereek! The Osprey is particularly well adapted to its fish diet, with reversible outer toes, closable nostrils to keep out water during dives, and backwards facing scales on the talons which act as barbs to help hold its catch. It locates its prey from the air, often hovering prior to plunging feet-first into the water to seize a fish. As it rises back into flight the fish is turned head forward to reduce drag. The 'barbed' talons are such effective tools for grasping fish that, on occasion, an Osprey may be unable to release a fish that is heavier than expected. This can cause the Osprey to be pulled into the water, where it may either swim to safety or succumb to hypothermia and drown. The osprey breeds by freshwater lakes, and sometimes on coastal brackish waters. The nest is a large heap of sticks built in trees, rocky outcrops, telephone poles or artificial platforms. In some regions with high Osprey densities, such as Chesapeake Bay, USA, most ospreys do not start breeding until they are five to seven years old, and there may be a shortage of suitable tall structures. If there are no nesting sites available, young ospreys may be forced to delay breeding. To ease this problem, posts may be erected to provide more sites suitable for nest building. | |

Ciconiiformes (storks, herons, egrets)

| Ardea herodias (Great Blue Heron) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The Great Blue Heron, Ardea herodias, is a wading bird of the heron family, common all over North and Central America as well as the West Indies and the Galápagos Islands, except in deserts and high mountains where there is no water for it to wade in. The Great Blue Heron is the largest heron in North America.

Adults have blue-grey wings and back and a white head with a black cap and a long black plume. The face is white, with a black streak extending from behind the eye to the back of the head. They have a long neck, streaked with white, rust-brown, and black, which is generally held in a s-curve while wading, and a short tail. The beak is yellow, long, and and tapers to a point. Legs are long, and greenish-yellow in color. In flight, the head is held close to and aligned with the body by a downward bend in the long neck. The long legs trail behind. This bird flies with strong deliberate wing beats. The males and females appear relatively similar, but males have a puffy plume of feathers behind their heads, and tend to be slightly larger than females. It is found throughout most of North America, including Alaska, Quebec and Nova Scotia. The range extends south through Florida, Mexico and the Caribbean to South America. Great blue herons can be found in a range of habitats, in fresh and saltwater marshes, mangrove swamps, flooded meadows, rivers, lake edges, or shorelines, but they always live near bodies of water. Generally, they nest in trees or bushes that stand near water. It feeds in shallow water or at the water's edge during both the night and the day, but especially around dawn and dusk. Herons locate their food by sight and generally swallow it whole. Herons have been known to choke on prey that is too large.It uses its long legs to wade through shallow water, and spears fish or frogs with its long, sharp bill. Its diet can also include insects, snakes, turtles, rodents and small birds. It is generally a solitary feeder. Individuals usually forage while standing in water, but will also forage in fields or drop from the air, or a perch, into water. As large wading birds, Great Blue Herons are able to feed in deeper waters, and thus are able to exploit a niche not open to most other heron species. This species usually breeds in colonies, in trees close to lakes or other wetlands; often with other species of herons. These groups are called heronry (more accurately than "rookery"). The size of these colonies may be large, ranging between 5 – 500 nests per colony, with an average of approximately 160 nests per colony. Great Blues build a bulky stick nest, and the female lays three to six pale blue eggs. One brood is raised each year. If the nest is abandoned or destroyed, the female may lay a replacement clutch. Reproduction is negatively affected by human disturbance, particularly during the beginning of nesting. Repeated human intrusion into nesting areas often results in nest failure, with abandonment of eggs or chicks. Both parents feed the young at the nest by regurgitating food. Parent birds have been shown to consume up to 4 times as much food when they are feeding young chicks than when laying or incubating eggs. Eggs are incubated for approximately 28 days and hatch over a period of several days. The first chick to hatch usually becomes more experienced in food handling and aggressive interactions with siblings, and so often grows more quickly than the other chicks. Birds east of the Rocky Mountains in the northern part of their range are bird migratory and winter in Central America or northern South America. From the southern United States southwards and on the Pacific coast, they are year-round residents. | |