Difference between revisions of "AY Honors/Trees - Advanced/Answer Key"

m (41 revisions: import with history from WB) |

m (- Category of AYHAB) |

||

| (21 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{HonorSubpage}} |

| − | + | <section begin="Body" /> | |

| − | {{ | + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=1}} |

| − | ==2. Collect, identify, press, and mount leaves of 35 different species of trees. | + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:30--> |

| − | {{: | + | </noinclude> |

| + | <!-- 1. Have the Trees honor. --> | ||

| + | {{honor_prerequisite|honor=Trees}} | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 1 --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=2}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:31--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | <!-- 2. Collect, identify, press, and mount leaves of 35 different species of trees. --> | ||

| + | {{:AY Honors/Leaf_collection}} | ||

| − | ==3. Separately collect, press, mount, and label specimens that demonstrate the following terms:== | + | <!--T:32--> |

| − | + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | |

| − | + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 2 --> | |

| − | + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=3}} | |

| − | + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:33--> | |

| − | + | </noinclude> | |

| − | + | <!-- 3. Separately collect, press, mount, and label specimens that demonstrate the following terms: --> | |

| − | + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | |

| − | + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=3a}} | |

| − | + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:34--> | |

| − | + | </noinclude> | |

| − | + | The margins of the leaf have forward-pointing teeth. (cherry) | |

| − | + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | |

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 3a --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=3b}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:35--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | Each serration on the margin of the leaf has smaller serrations of its own. (elm) | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 3b --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=3c}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:36--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | The entire margin of the leaf is smooth. (sassafras, pawpaw, osage orange) | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 3c --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=3d}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:37--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | The margins of the leaf have rounded teeth. (beech) | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 3d --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=3e}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:38--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | The margins of the leaf have symmetrical teeth. (chestnut) | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 3e --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=3f}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:39--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | The margins of the leaf have large, smooth indentations that do not go all the way to the centerline. (oaks) | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 3f --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=3g}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:40--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | The margins of the leaf are deeply and sharply cut. (Maples) | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 3g --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=3h}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:41--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | Three or more leaves are attached to a single node on a branch or stem. | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 3h --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=3i}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:42--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | Leaves are paired on a node on opposite sides of the stem. (sumacs, hickorys, walnut) | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 3i --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=3j}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:43--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | Only a single leaf grows from a node. | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 3j --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=3k}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:44--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | A leaf consisting of multiple leaflets. (sumac, locust) | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 3k --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=3l}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:45--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | Like pinnately compound leaves except the leaflets have leaflets of their own. (devil's walking stick, mimosa). | ||

| + | <!--T:3--> | ||

[[Image:Leaf morphology no title.png|thumb|700px]] | [[Image:Leaf morphology no title.png|thumb|700px]] | ||

<br style="clear:both"> | <br style="clear:both"> | ||

| − | ==4a. Describe the advantages in using the Latin or scientific names.== | + | <!--T:46--> |

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 3l --> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 3 --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=4}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | <!-- 4. Complete the following --> | ||

| + | ===4a. Describe the advantages in using the Latin or scientific names.=== <!--T:4--> | ||

[[Image:Maclura pomifera2.jpg|thumb|180px|Osage Orange]] | [[Image:Maclura pomifera2.jpg|thumb|180px|Osage Orange]] | ||

| − | + | Latin names (such as ''Quercus alba'' which is white oak) are useful because they are absolutely unique for each species. Thus, the Latin name can be used in international settings without ambiguity. Sometimes a given species will go by one name on one region, and by another name in another region. | |

| − | For example, the Osage-orange (''Maclura pomifera'') is also known as mock orange, hedge-apple, horse-apple, hedge ball, bois d'arc, bodark (in Texas), and bow wood. A common slang term for it is also monkey brain or monkey ball due to its brainlike appearance. | + | <!--T:5--> |

| + | For example, the Osage-orange (''Maclura pomifera'') is also known as mock orange, hedge-apple, horse-apple, hedge ball, bois d'arc, bodark (in Texas), and bow wood. A common slang term for it is also monkey brain or monkey ball due to its brainlike appearance. | ||

| − | Bows are made from many types of wood, including yew and red elm, so "bow wood" could mean any of these. | + | <!--T:6--> |

| + | Bows are made from many types of wood, including yew and red elm, so "bow wood" could mean any of these. However, ''Maclura pomifera'' means only one thing. | ||

| + | <!--T:7--> | ||

<br style="clear:both"> | <br style="clear:both"> | ||

| − | ==4b. Of what use are the two parts of a scientific name?== | + | ===4b. Of what use are the two parts of a scientific name?=== <!--T:8--> |

| − | The first part of the scientific name is the genus, and the second part is the species. | + | The first part of the scientific name is the genus, and the second part is the species. We have already discussed ''Quercus alba'' - the white oak, so let's expand on that. There are many, many different species of oak, and they are all in the genus ''Quercus''. All these trees produce acorns, and they are closely related to one another. Grouping them into a common genus recognizes their similarities, while separating them by species recognizes their differences. |

| − | ==5. Name six families of trees in the angiosperm class and three families in the gymnosperm class. | + | <!--T:47--> |

| − | ===Angiosperms=== | + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> |

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 4 --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=5}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | <!-- 5. Name six families of trees in the angiosperm class and three families in the gymnosperm class. --> | ||

| + | ===Angiosperms=== <!--T:48--> | ||

;Beech Family: Beeches, Chestnuts, Chinkapins, and Oaks | ;Beech Family: Beeches, Chestnuts, Chinkapins, and Oaks | ||

;Birch Family: Alders, Birches, Hornbeams, and Hazelnuts | ;Birch Family: Alders, Birches, Hornbeams, and Hazelnuts | ||

| Line 54: | Line 144: | ||

;Willow Family: Aspens, Poplars, and Willows | ;Willow Family: Aspens, Poplars, and Willows | ||

| − | ===Gymnosperms=== | + | ===Gymnosperms=== <!--T:10--> |

;Cedar or Cypress Family: Cedars, Cypresses, Junipers | ;Cedar or Cypress Family: Cedars, Cypresses, Junipers | ||

;Pine Family: Firs, Hemlocks, Pines, and Spruces | ;Pine Family: Firs, Hemlocks, Pines, and Spruces | ||

| Line 60: | Line 150: | ||

;Yew Family: Yews, Torreyas | ;Yew Family: Yews, Torreyas | ||

| − | ==6. Know and describe the function of leaves in the life of a tree. | + | <!--T:49--> |

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 5 --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=6}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:50--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | <!-- 6. Know and describe the function of leaves in the life of a tree. --> | ||

A leaf is the part of a plant specialized for photosynthesis. For this purpose, a leaf is typically flat and thin, to expose the cells containing chloroplast to light over a broad area, and to allow light to penetrate fully into the tissues. Leaves can store food and water. | A leaf is the part of a plant specialized for photosynthesis. For this purpose, a leaf is typically flat and thin, to expose the cells containing chloroplast to light over a broad area, and to allow light to penetrate fully into the tissues. Leaves can store food and water. | ||

| − | ==7. Name the families of trees in your area which have opposite leaves. | + | <!--T:51--> |

| − | This is a partial list of trees with opposite leaves. | + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> |

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 6 --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=7}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:52--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | <!-- 7. Name the families of trees in your area which have opposite leaves. --> | ||

| + | This is a partial list of trees with opposite leaves. There may be more in your area. | ||

| + | <!--T:13--> | ||

Maples, most Dogwoods, Ashes, Buckeyes, Buckthorn, Redwood, Paulownia, Lilac, Viburnum, Juniper, Black Mangrove, Olive, Piratebush, Boxwood, Southern Catalpa, Eucalyptus (gum), Pomegranate, and Elderberry. | Maples, most Dogwoods, Ashes, Buckeyes, Buckthorn, Redwood, Paulownia, Lilac, Viburnum, Juniper, Black Mangrove, Olive, Piratebush, Boxwood, Southern Catalpa, Eucalyptus (gum), Pomegranate, and Elderberry. | ||

| − | ==8. Define the following terms:== | + | <!--T:53--> |

| − | + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | |

| − | + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 7 --> | |

| − | + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=8}} | |

| − | + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:54--> | |

| − | + | </noinclude> | |

| − | + | <!-- 8. Define the following terms: --> | |

| − | + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | |

| − | + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=8a}} | |

| − | + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:55--> | |

| − | + | </noinclude> | |

| − | + | Outgrowths on either side of the petiole. | |

| − | + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | |

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 8a --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=8b}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:56--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | A leaf's stem. | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 8b --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=8c}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:57--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | The flat portion of a leaf, the blade may simple or be divided into leaflets (compound). | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 8c --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=8d}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:58--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | Pitch is the name for any of a number of highly viscous liquids which appear solid. Pitch can be made from petroleum products or plants. Pitch produced from plants is also known as resin. | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 8d --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=8e}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:59--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | Examination of the cross-section of a log will reveal dark wood near the center, and light-colored wood near the bark. The dark wood near the center is heartwood. As a tree increases in age and diameter an inner portion of the sapwood becomes inactive and finally ceases to function, as the cells die. This inert or dead portion is called heartwood. | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 8e --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=8f}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:60--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | Sapwood is comparatively new wood, comprising living cells in the growing tree. All wood in a tree is first formed as sapwood. Its principal functions are to conduct water from the roots to the leaves and to store up and give back according to the season the food prepared in the leaves. | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 8f --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=8g}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:61--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | The inner portion of a growth ring is formed early in the growing season, when growth is comparatively rapid (hence the wood is less dense) and is known as "early wood" or "spring wood" | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 8g --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=8h}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:62--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | The outer portion of the growth ring is the "late wood" (and has sometimes been termed "summerwood", often being produced in the summer, though sometimes in the autumn) and is more dense. | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 8h --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=8i}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:63--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | Annual rings can be seen in a horizontal cross section cut through the trunk of a tree. Visible rings result from the change in growth speed through the seasons of the year, thus one ring usually marks the passage of one year in the life of the tree. The rings are more visible in temperate zones, where the seasons differ more markedly. | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 8i --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=8j}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:64--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | A layer of cells just under the bark of a tree. This layer is only one cell deep, and it produces all the new wood in a tree. | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 8j --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=8k}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:65--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | A vein in a tree that brings water from the roots into the leaf. | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 8k --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=8l}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:66--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | A vein in a tree that moves sap out, the latter containing the glucose (a form of sugar) produced by photosynthesis in the leaf. | ||

| − | ==9. What families of trees have:== | + | <!--T:67--> |

| − | + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | |

| − | + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 8l --> | |

| − | + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 8 --> | |

| − | + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=9}} | |

| − | + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:68--> | |

| − | + | </noinclude> | |

| − | + | <!-- 9. What families of trees have: --> | |

| − | + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | |

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=9a}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:69--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | Hawthorn, locust | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 9a --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=9b}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:70--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | Oak, birch, willow, alder, poplar | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 9b --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=9c}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:71--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | Maple, ash, elm | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 9c --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=9d}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:72--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | Oak | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 9d --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=9e}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:73--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | Locust (and other legumes), mimosa | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 9e --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=9f}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:74--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | Sourwood, paulownia, eucalyptus | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 9f --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=9g}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:75--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | Hickory, beech, birch, walnut | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 9g --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=9h}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:76--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | Yew, mulberry, elderberry, nannyberry | ||

| − | ==10. Identify ten deciduous trees by their “winter” characteristics, (features other than leaves) such as twig and bud, characteristic form, and growth habits. | + | <!--T:77--> |

| − | ===By bark=== | + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> |

| − | The bark of many trees is easily recognizable, and in some cases, using the bark to identify the tree is easier than using the leaves. | + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 9h --> |

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 9 --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=10}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | <!-- 10. Identify ten deciduous trees by their “winter” characteristics, (features other than leaves) such as twig and bud, characteristic form, and growth habits. --> | ||

| + | ===By bark=== <!--T:78--> | ||

| + | The bark of many trees is easily recognizable, and in some cases, using the bark to identify the tree is easier than using the leaves. | ||

| + | <!--T:17--> | ||

[[Image:American_sycamore_bark.jpg|thumb|right|American Sycamore]] | [[Image:American_sycamore_bark.jpg|thumb|right|American Sycamore]] | ||

| − | ;Sycamore: The bark of a sycamore tree could best be described as "patchy." | + | ;Sycamore: The bark of a sycamore tree could best be described as "patchy." Large scales of the outer brown, gray, and white bark flake off to reveal a green bark beneath. Sycamores are most often found near streams, rivers, ponds, or other sources of water. |

<br style="clear:both"> | <br style="clear:both"> | ||

| + | <!--T:18--> | ||

[[Image:Betula papyrifera1.jpg|thumb|right|The bark of a Paper Birch]] | [[Image:Betula papyrifera1.jpg|thumb|right|The bark of a Paper Birch]] | ||

| − | ;Paper Birch: The bark of the paper birch is white, commonly brightly so, flaking in fine horizontal strips, and often with small black marks and scars. It is papery, with thin wisps peeling off. | + | ;Paper Birch: The bark of the paper birch is white, commonly brightly so, flaking in fine horizontal strips, and often with small black marks and scars. It is papery, with thin wisps peeling off. The tears in the bark run laterally, and there are characteristic "dotted lines" running in the same direction. |

<br style="clear:both"> | <br style="clear:both"> | ||

[[Image:IN Hoot Woods.jpg|thumb|right|The bark of a Beech]] | [[Image:IN Hoot Woods.jpg|thumb|right|The bark of a Beech]] | ||

| − | ;Beech: Beech trees are similar to birch trees, but the bark does not peel off in paper-thin wisps. | + | ;Beech: Beech trees are similar to birch trees, but the bark does not peel off in paper-thin wisps. Also, the color is a bit more grey, and it lacks the horizontal "dotted lines" found on the birch. |

<br style="clear:both"> | <br style="clear:both"> | ||

| + | <!--T:19--> | ||

[[Image:Flowering Dogwood Cornus florida Trunk Bark 3100px.jpg|thumb|right|The bark of a Flowering Dogwood]] | [[Image:Flowering Dogwood Cornus florida Trunk Bark 3100px.jpg|thumb|right|The bark of a Flowering Dogwood]] | ||

;Dogwood: The bark of a mature dogwood breaks up into small scales. | ;Dogwood: The bark of a mature dogwood breaks up into small scales. | ||

<br style="clear:both"> | <br style="clear:both"> | ||

| − | ;Hackberry: The bark of the hackberry tree is warty. | + | <!--T:20--> |

| + | ;Hackberry: The bark of the hackberry tree is warty. These warts are typically .25 inches (6 mm) in diameter, and arranged in groups on the tree's trunk. | ||

| − | ;Hornbeam: The bark of the hornbeam (also known as ironwood) looks distinctively muscular. | + | <!--T:21--> |

| + | ;Hornbeam: The bark of the hornbeam (also known as ironwood) looks distinctively muscular. It is smooth and looks very much like the limb of a muscular human. Indeed it sometimes goes by the name "musclewood" for this very reason. | ||

| + | <!--T:22--> | ||

[[Image:Hickory07103.jpg|thumb|right|Shagbark Hickory]] | [[Image:Hickory07103.jpg|thumb|right|Shagbark Hickory]] | ||

;Shagbark Hickory: Mature Shagbarks are easy to recognize because, as their name implies, they have shaggy bark. This character is however only found on mature trees; young specimens have smooth bark. | ;Shagbark Hickory: Mature Shagbarks are easy to recognize because, as their name implies, they have shaggy bark. This character is however only found on mature trees; young specimens have smooth bark. | ||

<br style="clear:both"> | <br style="clear:both"> | ||

| − | ===By buds and twigs=== | + | ===By buds and twigs=== <!--T:23--> |

| − | Virginia Tech has a website at http://www.cnr.vt.edu/DENDRO/DENDROLOGY/syllabus/twigkey/location.htm which will aid you in identifying trees by their twigs. | + | Virginia Tech has a website at http://www.cnr.vt.edu/DENDRO/DENDROLOGY/syllabus/twigkey/location.htm which will aid you in identifying trees by their twigs. The arrangement and structure of buds on a twig are unique to many species, and therefore useful as an identification tool. In some cases, identification by twigs is more accurate than by leaves. The following trees are among the easiest to identify by their twigs: |

| + | <!--T:24--> | ||

;Alder: | ;Alder: | ||

;Maple: | ;Maple: | ||

| Line 129: | Line 356: | ||

;Honey Locust: | ;Honey Locust: | ||

| − | ===By Characteristic Form=== | + | ===By Characteristic Form=== <!--T:25--> |

| − | Some trees have a unique shape. | + | Some trees have a unique shape. If you learn to recognize trees by their shape, it is possible to identify them even from a great distance. |

<gallery> | <gallery> | ||

Image:Llandegfan Elm tree.jpg|Elm Tree | Image:Llandegfan Elm tree.jpg|Elm Tree | ||

| Line 140: | Line 367: | ||

;Lombardy Poplar: Lombardy Poplars are slender, columnar tree with branches pointed sharply upward. | ;Lombardy Poplar: Lombardy Poplars are slender, columnar tree with branches pointed sharply upward. | ||

| − | ===By Growth Habits=== | + | ===By Growth Habits=== <!--T:26--> |

| − | Some trees have preferred habitats. | + | Some trees have preferred habitats. The American Sycamore, for example, tends to grow near plentiful water sources. Because of its distinctive bark, it is usually easier to find creeks by finding the sycamore than it is to find the sycamore by finding a creek. |

| − | + | <!--T:79--> | |

| − | + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | |

| − | + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 10 --> | |

| − | + | <noinclude><translate></noinclude> | |

| + | ==References== <!--T:27--> | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseHonorPage}} | ||

Latest revision as of 00:25, 15 July 2022

1

For tips and instruction see Trees.

2

Unless you are already very familiar with the trees in your area, you will need to get a field guide on trees for this activity. Illustrating all the tree species you may encounter is well beyond the scope of a single chapter in an answer book!

It is best to collect the leaves in the spring or early summer before insects and weather have had a chance to damage them, but if you prefer, you can try to collect them in the fall when the colors change.

When you go out collecting, take the field guide with you. It is important to identify the leaves as you collect them, as you can look at more than just the leaves for identification. The bark, environment, buds, and shape of the tree are all important clues to the tree's species. This is especially important if you wish to differentiate trees of the same genus (such as black cherry, pin cherry, choke cherry, etc.).Indeed, proper identification may not be possible from just the leaf.

Collect leaves that are typical for the tree, but remember - smaller leaves are going to be easier to fit onto an 8.5x11 inch sheet of paper.

Press the leaves by placing them on some sort of absorbent paper - newspaper, paper towels, tissues, etc. Then place these under a stack of books or in a leaf press. After two weeks, the leaves should be flattened, dried, and well-preserved. Evergreens such as spruce and fir are difficult to preserve this way as the needles will fall off. The more ambitious may wish to encase the leaves in epoxy, as this preserves the color and eliminates the need for pressing (meaning the leaves also retain their three dimensional features).

Once the leaves have been pressed, you can glue, tape, or laminate them onto notebook paper. Use loose-leaf if you wish to rearrange them later. You may also place the pressed leaves between two sheets of wax paper, cover with a towel, and iron.

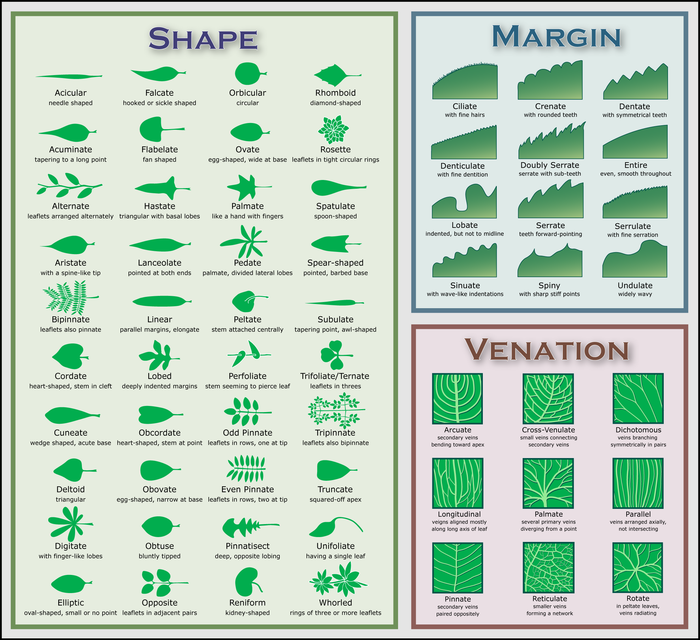

3

3a

The margins of the leaf have forward-pointing teeth. (cherry)

3b

Each serration on the margin of the leaf has smaller serrations of its own. (elm)

3c

The entire margin of the leaf is smooth. (sassafras, pawpaw, osage orange)

3d

The margins of the leaf have rounded teeth. (beech)

3e

The margins of the leaf have symmetrical teeth. (chestnut)

3f

The margins of the leaf have large, smooth indentations that do not go all the way to the centerline. (oaks)

3g

The margins of the leaf are deeply and sharply cut. (Maples)

3h

Three or more leaves are attached to a single node on a branch or stem.

3i

Leaves are paired on a node on opposite sides of the stem. (sumacs, hickorys, walnut)

3j

Only a single leaf grows from a node.

3k

A leaf consisting of multiple leaflets. (sumac, locust)

3l

Like pinnately compound leaves except the leaflets have leaflets of their own. (devil's walking stick, mimosa).

4

4a. Describe the advantages in using the Latin or scientific names.

Latin names (such as Quercus alba which is white oak) are useful because they are absolutely unique for each species. Thus, the Latin name can be used in international settings without ambiguity. Sometimes a given species will go by one name on one region, and by another name in another region.

For example, the Osage-orange (Maclura pomifera) is also known as mock orange, hedge-apple, horse-apple, hedge ball, bois d'arc, bodark (in Texas), and bow wood. A common slang term for it is also monkey brain or monkey ball due to its brainlike appearance.

Bows are made from many types of wood, including yew and red elm, so "bow wood" could mean any of these. However, Maclura pomifera means only one thing.

4b. Of what use are the two parts of a scientific name?

The first part of the scientific name is the genus, and the second part is the species. We have already discussed Quercus alba - the white oak, so let's expand on that. There are many, many different species of oak, and they are all in the genus Quercus. All these trees produce acorns, and they are closely related to one another. Grouping them into a common genus recognizes their similarities, while separating them by species recognizes their differences.

5

Angiosperms

- Beech Family

- Beeches, Chestnuts, Chinkapins, and Oaks

- Birch Family

- Alders, Birches, Hornbeams, and Hazelnuts

- Cashew Family

- Smoketree and Sumacs

- Custard-Apple Family

- Pawpaw and Pond apple

- Elm Family

- Elms and Hackberries

- Horsechestnut Family

- Buckeyes and Horsechestnuts

- Laurel Family

- Laurels, Redbay, and Sassafras

- Legume Family

- Acacias, Redbuds, and Locusts

- Magnolia Family

- Magnolias, and Yellow (Tulip) Poplar

- Maple Family

- Maples

- Mulberry Family

- Figs, Mulberries, and Osage Oranges

- Palm Family

- Coconuts, Dates, Palms, and Palmettos

- Rose Family

- Apples, Peaches, Pears, and Plums

- Sycamore Family

- Sycamores

- Walnut Family

- Hickories, and Walnuts

- Willow Family

- Aspens, Poplars, and Willows

Gymnosperms

- Cedar or Cypress Family

- Cedars, Cypresses, Junipers

- Pine Family

- Firs, Hemlocks, Pines, and Spruces

- Redwood Family

- Redwood, Giant Sequoia, Baldcypress

- Yew Family

- Yews, Torreyas

6

A leaf is the part of a plant specialized for photosynthesis. For this purpose, a leaf is typically flat and thin, to expose the cells containing chloroplast to light over a broad area, and to allow light to penetrate fully into the tissues. Leaves can store food and water.

7

This is a partial list of trees with opposite leaves. There may be more in your area.

Maples, most Dogwoods, Ashes, Buckeyes, Buckthorn, Redwood, Paulownia, Lilac, Viburnum, Juniper, Black Mangrove, Olive, Piratebush, Boxwood, Southern Catalpa, Eucalyptus (gum), Pomegranate, and Elderberry.

8

8a

Outgrowths on either side of the petiole.

8b

A leaf's stem.

8c

The flat portion of a leaf, the blade may simple or be divided into leaflets (compound).

8d

Pitch is the name for any of a number of highly viscous liquids which appear solid. Pitch can be made from petroleum products or plants. Pitch produced from plants is also known as resin.

8e

Examination of the cross-section of a log will reveal dark wood near the center, and light-colored wood near the bark. The dark wood near the center is heartwood. As a tree increases in age and diameter an inner portion of the sapwood becomes inactive and finally ceases to function, as the cells die. This inert or dead portion is called heartwood.

8f

Sapwood is comparatively new wood, comprising living cells in the growing tree. All wood in a tree is first formed as sapwood. Its principal functions are to conduct water from the roots to the leaves and to store up and give back according to the season the food prepared in the leaves.

8g

The inner portion of a growth ring is formed early in the growing season, when growth is comparatively rapid (hence the wood is less dense) and is known as "early wood" or "spring wood"

8h

The outer portion of the growth ring is the "late wood" (and has sometimes been termed "summerwood", often being produced in the summer, though sometimes in the autumn) and is more dense.

8i

Annual rings can be seen in a horizontal cross section cut through the trunk of a tree. Visible rings result from the change in growth speed through the seasons of the year, thus one ring usually marks the passage of one year in the life of the tree. The rings are more visible in temperate zones, where the seasons differ more markedly.

8j

A layer of cells just under the bark of a tree. This layer is only one cell deep, and it produces all the new wood in a tree.

8k

A vein in a tree that brings water from the roots into the leaf.

8l

A vein in a tree that moves sap out, the latter containing the glucose (a form of sugar) produced by photosynthesis in the leaf.

9

9a

Hawthorn, locust

9b

Oak, birch, willow, alder, poplar

9c

Maple, ash, elm

9d

Oak

9e

Locust (and other legumes), mimosa

9f

Sourwood, paulownia, eucalyptus

9g

Hickory, beech, birch, walnut

9h

Yew, mulberry, elderberry, nannyberry

10

By bark

The bark of many trees is easily recognizable, and in some cases, using the bark to identify the tree is easier than using the leaves.

- Sycamore

- The bark of a sycamore tree could best be described as "patchy." Large scales of the outer brown, gray, and white bark flake off to reveal a green bark beneath. Sycamores are most often found near streams, rivers, ponds, or other sources of water.

- Paper Birch

- The bark of the paper birch is white, commonly brightly so, flaking in fine horizontal strips, and often with small black marks and scars. It is papery, with thin wisps peeling off. The tears in the bark run laterally, and there are characteristic "dotted lines" running in the same direction.

- Beech

- Beech trees are similar to birch trees, but the bark does not peel off in paper-thin wisps. Also, the color is a bit more grey, and it lacks the horizontal "dotted lines" found on the birch.

- Dogwood

- The bark of a mature dogwood breaks up into small scales.

- Hackberry

- The bark of the hackberry tree is warty. These warts are typically .25 inches (6 mm) in diameter, and arranged in groups on the tree's trunk.

- Hornbeam

- The bark of the hornbeam (also known as ironwood) looks distinctively muscular. It is smooth and looks very much like the limb of a muscular human. Indeed it sometimes goes by the name "musclewood" for this very reason.

- Shagbark Hickory

- Mature Shagbarks are easy to recognize because, as their name implies, they have shaggy bark. This character is however only found on mature trees; young specimens have smooth bark.

By buds and twigs

Virginia Tech has a website at http://www.cnr.vt.edu/DENDRO/DENDROLOGY/syllabus/twigkey/location.htm which will aid you in identifying trees by their twigs. The arrangement and structure of buds on a twig are unique to many species, and therefore useful as an identification tool. In some cases, identification by twigs is more accurate than by leaves. The following trees are among the easiest to identify by their twigs:

- Alder

- Maple

- Apple

- Hawthorn

- Black Locust

- Honey Locust

By Characteristic Form

Some trees have a unique shape. If you learn to recognize trees by their shape, it is possible to identify them even from a great distance.

- Elm

- Elm trees are generally vase shaped

- Willow

- Note the dense, thin branches in the top of the tree.

- Lombardy Poplar

- Lombardy Poplars are slender, columnar tree with branches pointed sharply upward.

By Growth Habits

Some trees have preferred habitats. The American Sycamore, for example, tends to grow near plentiful water sources. Because of its distinctive bark, it is usually easier to find creeks by finding the sycamore than it is to find the sycamore by finding a creek.