Difference between revisions of "AY Honors/Model Railroad/Answer Key"

m (Transwiki:Containerization moved to AY Honor Model Railroad: transwiki import of w:Containerization) |

m (110 revisions from w:Refrigerator car) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{globalise}} |

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Art2471940.jpg|thumb|350px|right|A [[World War II]]-era wood-sided, ice bunker "reefer" of the American Refrigerator Transit Company (ART), one specially-designated for the transport of dairy products, ''circa'' 1940.]] |

| − | + | ||

| − | ''' | + | A '''refrigerator car''' (or '''"reefer"''') is a [[Refrigeration|refrigerated]] [[boxcar]], a piece of [[railroad]] [[rolling stock]] designed to carry perishable freight at specific temperatures. Refrigerator cars differ from simple [[Thermal insulation|insulated]] boxcars and [[Ventilation (architecture)|ventilated]] boxcars (commonly used for transporting [[fruit]]), neither of which are fitted with cooling apparatus. Reefers can be [[ice]]-[[Refrigeration|cooled]], come equipped with any one of a variety of mechanical refrigeration systems, or utilize [[carbon dioxide]] (either as [[dry ice]], or in liquid form) as a cooling agent. [[Milk]] cars (and other types of "express" reefers) may or may not include a cooling system, but are equipped with high-speed [[bogie|trucks]] and other modifications that allow them to travel with [[train|passenger trains]]. |

| + | |||

| + | Reefer applications can be divided into five broad groups: 1) [[dairy]] and [[poultry]] producers require refrigeration and special interior racks; 2) [[fruit]] and [[vegetable]] reefers tend to see seasonal use, and are generally used for long-distance shipping (for some shipments, only ventilation is necessary to remove the heat created by the ripening process); 3) [[Manufacturing|manufactured]] [[food]]s (such as [[Canning|canned goods]] and [[candy]]) as well as [[beer]] and [[wine]] do not require refrigeration, but do need the protection of an insulated car; 4) meat reefers come equipped with specialized beef rails for handling sides of meat, and [[brine]]-tank refrigeration to provide lower temperatures (most of these units are either owned or leased by meat packing firms); and 5) [[fish]] and [[seafood]]s are transported, packed in wooden or [[Polystyrene#Solid foam|foam polystyrene]] box with crushed ice, and ice bunkers are not used generally. | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | ===Background=== |

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:IC 14713.jpg|thumb|300px|right|[[Illinois Central Railroad]] #14713, a ventilated fruit car dating from 1893.]] |

| + | |||

| + | After the end of the [[American Civil War]], [[Chicago, Illinois]] emerged as a major [[railway]] center for the [[Distribution (business)|distribution]] of livestock raised on the [[Great Plains]] to Eastern markets.<ref>Boyle and Estrada</ref> Getting the animals to market required herds to be driven up to 1,200 miles (2,000 km) to [[railhead]]s in [[Kansas City, Missouri]], where they were loaded into specialized [[Stock car (rail)|stock car]]s and [[transport]]ed live ("on-the-hoof") to regional processing centers. Driving cattle across the plains also caused tremendous weight loss, with some animals dying in transit. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Upon arrival at the local processing facility, livestock were either [[slaughter]]ed by wholesalers and delivered fresh to nearby butcher shops for retail sale, smoked, or packed for shipment in barrels of salt. Costly inefficiencies were inherent in transporting live animals by rail, particularly the fact that about sixty percent of the animal's mass is inedible. The death of animals weakened by the long drive further increased the per-unit shipping cost. Meat packer [[Gustavus Franklin Swift|Gustavus Swift]] sought a way to ship dressed meats from his Chicago packing plant to eastern markets. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Early attempts at refrigerated transport=== | ||

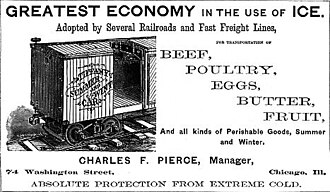

| + | [[Image:Tiffany ad 1879 CBD.jpg|thumb|325px|left|An advertisement taken from the 1st edition (1879) of the ''Car-Builders Dictionary'' for the '''Tiffany Refrigerator Car Company''', a pioneer in the design of refrigerated railroad cars.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Attempts were made during the mid-1800s to ship [[agriculture|agricultural]] products by rail. As early as 1842, the [[Western Railroad of Massachusetts]] was reported in the June 15 edition of the ''Boston Traveler'' to be experimenting with innovative [[freight car]] designs capable of carrying all types of perishable goods without spoilage.<ref>White, p. 31</ref> The first refrigerated boxcar entered service in June 1851, on the [[Northern Railroad of New York]] (or NRNY, which later became part of the [[Rutland Railroad]]). This "icebox on wheels" was a limited success since it was only functional in cold weather. That same year, the [[Ogdensburg and Lake Champlain Railroad]] (O&LC) began shipping butter to Boston in purpose-built freight cars, utilizing ice for cooling. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The first consignment of dressed beef left the [[Union Stock Yards|Chicago stock yards]] in 1857 in ordinary [[boxcar]]s retrofitted with bins filled with ice. Placing meat directly against ice resulted in discoloration and affected the taste, and proved impractical. During the same period Swift experimented by moving cut meat using a string of ten boxcars with their doors removed, and made a few test shipments to New York during the winter months over the [[Grand Trunk Railway]] (GTR). The method proved too limited to be practical. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Interior of ice bunker reefer.jpg|thumb|250px|right|The interior of a typical ice-bunker reefer from the 1920s. The wood sheathing was replaced by [[plywood]] within twenty years. Vents in the bunker at the end of the car, along with slots in the wood floor racks, allowed cool air to circulate around the contents.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Detroit, Michigan|Detroit's]] [[William Davis]] patented a refrigerator car that employed metal racks to suspend the carcasses above a frozen mixture of ice and salt. He sold the design in 1868 to [[George Hammond (industrialist)|George H. Hammond]], a Detroit meat packer, who built a set of cars to transport his products to Boston using ice from the [[Great Lakes]] for cooling.<ref>White, p. 33</ref> The load had the tendency of swinging to one side when the car entered a curve at high speed, and use of the units was discontinued after several derailments. In 1878 Swift hired engineer Andrew Chase to design a ventilated car that was well insulated, and positioned the ice in a compartment at the top of the car, allowing the chilled air to flow naturally downward.<ref>White, p. 45</ref> The meat was packed tightly at the bottom of the car to keep the [[center of gravity]] low and to prevent the cargo from shifting. Chase's design proved to be a practical solution to providing temperature-controlled carriage of dressed meats, and allowed [[Swift and Company]] to ship their products across the United States and internationally. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Swift's attempts to sell Chase's design to major railroads were rebuffed, as the companies feared that they would jeopardize their considerable investments in [[Stock car (rail)|stock cars]], animal pens, and feedlots if refrigerated meat transport gained wide acceptance. In response, Swift financed the initial production run on his own, then — when the American roads refused his business — he contracted with the GTR (a railroad that derived little income from transporting live cattle) to haul the cars into [[Michigan]] and then eastward through Canada. In 1880 the [[Peninsular Car Company]] (subsequently purchased by ACF) delivered the first of these units to Swift, and the Swift Refrigerator Line (SRL) was created. Within a year the Line’s roster had risen to nearly 200 units, and Swift was transporting an average of 3,000 carcasses a week to [[Boston, Massachusetts]]. Competing firms such as [[Armour and Company]] quickly followed suit. By 1920 the SRL owned and operated 7,000 of the ice-cooled rail cars. The [[General American Transportation Corporation]] would assume ownership of the line in 1930. | ||

| − | + | [[Image:One of the first cars out of the Detroit plant of American Car & Foundry - Built 1899 for Swift Refrigerator Line - Chicago Historical Society.jpg|thumb|325px|right|A builder's photo of one of the first refrigerator cars to come out of the [[Detroit]] plant of the [[American Car and Foundry Company]] (ACF), built in 1899 for the [[Swift Refrigerator Line]].]] | |

| − | === | + | '''Live cattle and dressed beef deliveries to New York ([[short tons]]):''' |

| − | + | {| class="toccolours" | |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |align=center | <small>''(Stock Cars)'' | ||

| + | |align=center | <small>''(Refrigerator Cars)'' | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |align=center | '''Year | ||

| + | |align=center | '''Live Cattle | ||

| + | |align=center | '''Dressed Beef | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1882 | ||

| + | |align=center | 366,487 | ||

| + | |align=center | 2,633 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1883 | ||

| + | |align=center | 392,095 | ||

| + | |align=center | 16,365 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1884 | ||

| + | |align=center | 328,220 | ||

| + | |align=center | 34,956 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1885 | ||

| + | |align=center | 337,820 | ||

| + | |align=center | 53,344 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1886 | ||

| + | |align=center | 280,184 | ||

| + | |align=center | 69,769 | ||

| + | |} | ||

| − | + | <small>The subject cars travelled on the [[Erie Railroad|Erie]], [[Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad|Lackawanna]], [[New York Central Railroad|New York Central]], and [[Pennsylvania Railroad|Pennsylvania]] railroads.</small> | |

| − | + | <small>Source: ''Railway Review'', January 29, 1887, p. 62.</small> | |

| − | + | [[Image:Early refrigerator car design circa 1870.jpg|thumb|325px|right|A ''circa'' 1870 refrigerator car design. Hatches in the roof provided access to the ice tanks at each end.]] | |

| − | + | '''19th Century American Refrigerator Cars:''' | |

| + | {| class="toccolours" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |align=center | '''Year | ||

| + | |align=center | '''Private Lines | ||

| + | |align=center | '''Railroads | ||

| + | |align=center | '''Total | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1880 | ||

| + | |align=center | 1,000 ''est. | ||

| + | |align=center | 310 | ||

| + | |align=center | 1,310 ''est. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1885 | ||

| + | |align=center | 5,010 ''est. | ||

| + | |align=center | 990 | ||

| + | |align=center | 6,000 ''est. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1890 | ||

| + | |align=center | 15,000 ''est. | ||

| + | |align=center | 8,570 | ||

| + | |align=center | 23,570 ''est. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1895 | ||

| + | |align=center | 21,000 ''est | ||

| + | |align=center | 7,040 | ||

| + | |align=center | 28,040 ''est. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | 1900 | ||

| + | |align=center | 54,000 ''est. | ||

| + | |align=center | 14,500 | ||

| + | |align=center | 68,500 ''est. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| − | + | <small>Source: ''Poor's Manual of Railroads'' and [[Interstate Commerce Commission|ICC]] and [[U.S. Census]] reports.</small> | |

| − | + | ===The "Ice Age"=== | |

| + | The use of ice to refrigerate and thus preserve food dates back to prehistoric times. Through the ages, the seasonal harvesting of snow and ice was a regular practice of many cultures. China, [[Ancient Greece|Greece]], and [[Ancient Rome|Rome]] stored ice and snow in caves or dugouts lined with straw or other insulating materials. Rationing of the ice allowed the preservation of foods during hot periods, a practice that was successfully employed for centuries. For most of the 1800s, natural ice (harvested from ponds and lakes) was used to supply refrigerator cars. At high altitudes or northern latitudes, one foot tanks were often filled with water and allowed to freeze. Ice was typically cut into blocks during the winter and stored in insulated warehouses for later use, with sawdust and hay packed around the ice blocks to provide additional insulation. A late-19th century wood-bodied reefer required reicing every 250 to {{convert|400|mi|km}}. | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Top icing reefer.jpg|thumb|150px|right|Top icing of bagged vegetables in a refrigerator car.]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The | + | By the turn of the 20th century manufactured ice became more common. The [[Pacific Fruit Express]] (PFE), for example, maintained 7 natural harvesting facilities, and operated 18 artificial ice plants. Their largest plant (located in [[Roseville, California]]) produced 1,200 short tons of ice daily, and Roseville’s docks could accommodate up to 254 cars. At the industry’s peak, 13 million short tons of ice was produced for refrigerator car use annually. |

| − | === | + | ===="Top Icing"==== |

| − | + | Top icing is the practice of placing a 2 to {{convert|4|in|mm|sing=on}} layer of crushed ice on top of agricultural products that have high respiration rates, need high relative humidity, and benefit from having the cooling agent sit directly atop the load (or within individual boxes). Cars with pre-cooled fresh produce were top iced just before shipment. Top icing added considerable dead weight to the load. Top-icing a {{convert|40|ft|m|sing=on}} reefer required in over 10,000 pounds of ice. It had been postulated that as the ice melts, the resulting chilled water would trickle down through the load to continue the cooling process. It was found, however, that top-icing only benefited the uppermost layers of the cargo, and that the water from the melting ice often passed through spaces between the cartons and pallets with little or no cooling effect. It was ultimately determined that top-icing is useful only in preventing an increase in temperature, and was eventually discontinued. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <gallery> | |

| + | Image:Ice Harvesting on Lake St Clair Michigan circa 1905--photograph courtesy Detroit Publishing Company.jpg|Men harvest ice on [[Michigan|Michigan's]] [[Lake Saint Clair]], ''circa'' 1905. The ice was cut into blocks and hauled by wagon to a cold storage warehouse, and held until needed. | ||

| + | Image:Men loading ice blocks into reefers.jpg|Ice blocks (also called "cakes") are manually placed into reefers from a covered icing dock. Each block weighed between 200 and 400 pounds. Crushed ice was typically used for meat cars. | ||

| + | <!-- Deleted image removed: Image:GM&O Refrigerator.jpg|An early version of a field icing car loads a Merchants Despatch Transportation Co. reefer (bearing the herald of the [[Gulf, Mobile and Ohio Railroad|GM&O]]) in [[Norfolk, Virginia]] on April 19, 1955. --> | ||

| + | Image:Mechanical Ice Loader.jpg|The "business end" of a mechanical ice loading system services a line of Pacific Fruit Express refrigerator cars. Each car will require approximately 5½ short tons (5 [[metric ton]]s) of ice. | ||

| + | </gallery> | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Topping off FGE reefer with ice.jpg|thumb|150px|right|Workmen top off a reefer's top-mounted bunkers with crushed ice.]] | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The typical service cycle for an ice-cooled produce reefer (generally handled as a part of a block of cars): | |

| + | # The cars were cleaned with hot water or steam. | ||

| + | # Depending on the cargo, the cars might have undergone 4 hours of "pre-cooling" prior to loading, which entailed blowing in cold air through one ice hatch and allowing the warmer air to be expelled through the other hatches. The practice, dating back almost to the inception of the refrigerator car, saved ice and resulted in fresher cargo. | ||

| + | # The cars' ice bunkers were filled, either manually from an [http://www.uprr.com/aboutup/photos/pfe/graphics/24.jpg icing dock], via mechanical loading equipment, or (in locations where demand for ice was sporadic) using specially-designed [http://www.uprr.com/aboutup/photos/pfe/graphics/spe11-71.jpg field icing cars]. | ||

| + | # The cars were delivered to the shipper for loading, and the ice was topped-off. | ||

| + | # Depending on the cargo and destination, the cars may have been fumigated. | ||

| + | # The train would depart for the eastern markets. | ||

| + | # The cars were reiced in transit approximately once a day. | ||

| + | # Upon reaching their destination, the cars were unloaded. | ||

| + | # If in demand, the cars would be returned to their point of origin empty. If not in demand, the cars would be cleaned and possibly used for a dry shipment. | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | <gallery> |

| − | The | + | Image:Tiffany RRG 1877.jpg|This engraving of Tiffany’s original "Summer and Winter Car" appeared in the ''Railroad Gazette'' just before Joel Tiffany received his refrigerator car patent in July, 1877. Tiffany's design mounted the ice tank in a [[clerestory]] atop the car's roof, and relied on a train's motion to circulate cool air throughout the cargo space. |

| + | Image:Reefers-shorty-Armour-Kansas-City-3891-Pullman.jpg|A [[Pullman Company|Pullman]]-built "shorty" [[reefer]] bears the ''Armour Packing Co. · Kansas City'' logo, ''circa'' 1885. The name of the "patentee" was displayed on the car's exterior, a practice intended to "''...impress the shipper and intimidate the competition...''," even though most patents covered trivial or already-established design concepts. | ||

| + | Image:Reefers-shorty-ATSF-CM-type-1898-cyc ACF builders photo.jpg|A rare double-door refrigerator car utilized the "Hanrahan System of Automatic Refrigeration" as built by [[American Car and Foundry Company|ACF]], ''circa'' 1898. The car had a single, centrally located ice bunker which was said to offer better cold air distribution. The two segregated cold rooms were well suited for less-than-carload (LCL) shipments. | ||

| + | Image:Reefers-shorty-Anheuser-Busch-Malt-Nutrine ACF builders photo pre-1911.jpg|A pre-1911 "shorty" reefer bears an advertisement for [[Anheuser-Busch|Anheuser-Busch's]] ''Malt Nutrine'' tonic. The use of similar "billboard" [[advertising]] on [[freight car]]s was banned by the [[Interstate Commerce Commission]] in 1937, and thereafter cars so decorated could no longer be accepted for interchange between roads. | ||

| + | </gallery> | ||

| − | + | Refrigerator cars required effective insulation to protect their contents from temperature extremes. "[[felt|Hairfelt]]" derived from compressed cattle hair, sandwiched into the floor and walls of the car, was inexpensive but flawed — over its three- to four-year service life it would decay, rotting out the car's wooden partitions and tainting the cargo with a foul odor. The higher cost of other materials such as "Linofelt" (woven from [[flax]] fibers) or [[cork (material)|cork]] prevented their widespread adoption. Synthetic materials such as [[fiberglass]] and [[polystyrene]], both introduced after [[World War II]], offered the most cost-effective and practical solution. | |

| − | + | ===Mechanical refrigeration=== | |

| + | In the latter half of the 20th century mechanical refrigeration began to replace ice-based systems. In time, mechanical refrigeration units replaced the "armies" of personnel required to re-ice the cars. The "plug" door was introduced experimentally by P.F.E. (Pacific Fruit Express) in April 1947, when one of their R-40-10 series cars, #42626, was equipped with one. P.F.E.'s R-40-26 series reefers, designed in 1949 and built in 1951, were the first production series cars to be so equipped. In addition, the Santa Fe Railroad first used plug doors on their SFRD RR-47 series cars, which were also built in 1951. This type of door, provided a larger six foot opening, to facilitate car loading and unloading. These tight-fitting doors were better insulated and could maintain a more even temperature inside the car. By the mid-1970s the few remaining ice bunker cars were relegated to "top-ice" service, where crushed ice was applied atop the commodity. | ||

| − | + | <gallery> | |

| − | < | + | Image:Cutaway PFE mechanical.jpg|A cutaway illustration of a conventional mechanical refrigerator car, which typically contains in excess of 800 moving parts. |

| − | + | Image:ARMN 761511 20050529 IL Rochelle.jpg|A modern refrigerator car: note the grill at the lower right (the car's "A" end) where the mechanical refrigeration unit is housed. | |

| − | + | Image:ARMN 110386 detail photo by JS Rybak @ Clarke Ontario Canada April 2005.jpg|State-of-the-art mechanical refrigerator car designs place the removable, end-mounted refrigeration unit outside of the freight compartment in order to facilitate access for servicing or replacement. | |

| + | Image:Amtk74049.jpg|A modern mechanical refrigerator car, outfitted for high-speed service, bears the colors and markings of [[Amtrak Express]], [[Amtrak|Amtrak's]] freight and shipping service. | ||

| + | </gallery> | ||

| − | + | ===Cryogenic refrigeration=== | |

| + | [[Image:Cryx2038-1.jpg|thumb|325px|right|Cryogenic refrigerator cars, such as those owned and operated by Cryo-Trans, Inc., are used today to transport frozen food products, including [[french fries]]. Today, Cryo-Trans operates a fleet in excess of 515 cryogenic railcars.]] | ||

| − | The | + | The [[Topeka, Kansas]] shops of the Santa Fe Railway built five experimental refrigerator cars employing [[liquid nitrogen]] as the cooling agent in 1965. A mist of liquified nitrogen was released throughout the car if the temperature rose above a pre-determined level. Each car carried 3,000 [[pound (mass)|pound]]s (1,360 kg) of refrigerant and could maintain a temperature of minus 20 degrees [[Fahrenheit]] (−30 °C). During the 1990s, a few railcar manufacturers experimented with the use of [[liquid carbon dioxide]] (CO<small><sub >2</sub ></small>) as a cooling agent. The move was in response to rising fuel costs, and was an attempt to eliminate the standard mechanical refrigeration systems that required periodic maintenance. The CO<small><sub >2</sub ></small> system can keep the cargo frozen solid as long as 14 to 16 days. |

| − | Since | + | Several hundred "[[cryogenic]]" refrigerator cars were placed in service transporting frozen foodstuffs, though they failed to gain wide acceptance (due, in part, to the rising cost of liquid carbon dioxide). Since cryogenic refrigeration is a proven technology and environmentally friendly, the rising price of fuel and the increased availability of carbon dioxide from [[Kyoto Protocol]]-induced capturing techniques may lead to a resurgence in cryogenic railcar usage. [[Cryo-Trans, Inc.]] (founded in 1985) has since dedicated 200 of its refrigerated cars to wine transportation service. |

| − | === | + | ===Experimentation=== |

| − | + | ====Aluminum and stainless steel==== | |

| + | In 1946, the Pacific Fruit Express procured from the [[Consolidated Steel Corporation]] of [[Wilmington, California]] two {{convert|40|ft|m|sing=on}} [[aluminum]]-bodied ventilator refrigerator cars, to compare the durability of the lightweight alloy versus that of steel. It was hoped that weight savings (the units weighed almost 10,000 pounds less than a like-sized all-steel car) and better corrosion resistance would offset the higher initial cost. One of the aluminum car bodies was manufactured by [[Alcoa]] (PFE #44739), while the other was built by the [[Reynolds Metals|Reynolds Aluminum Company]] (PFE #45698). | ||

| − | The | + | The cars (outfitted with state-of-the-art fiberglass insulation and axle-driven fans for internal air circulation) traveled throughout the Southern Pacific and Union Pacific systems, where they were displayed to promote PFE's post-[[World War II]] modernization. Though both units remained in service over 15 years (#45698 was destroyed in a wreck in May 1962, while #44739 was scrapped in 1966), no additional aluminum reefers were constructed, cost being the likely reason. Also in 1946 the Consolidated Steel delivered the world's only reefer to have a [[stainless steel]] body to the Santa Fe Refrigerator Despatch. The {{convert|40|ft|m|sing=on}} car was equipped with convertible ice bunkers, side ventilation ducts, and axle-driven circulation fans. It was thought that stainless steel would better resist the corrosive deterioration resulting from salting the ice. |

| + | The one-of-a-kind unit entered service as #13000, but was subsequently redesignated as #1300, and later given #4150 in 1955.<ref>Hendrickson and Scholz, p. 8</ref> | ||

| − | + | <nowiki>#4150</nowiki> spent most of its life in express service. Cost was cited as the reason no additional units were ordered. The car was dismantled at [[Clovis, New Mexico]] in February, 1964. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===="Depression Baby"==== | |

| + | During the 1930s, the [[North American Car Company]] produced a one-of-a-kind, four-wheeled ice bunker reefer intended to serve the needs of specialized shippers who did not generate sufficient product to fill a full-sized refrigerator car. NADX #10000 was a 22-foot-long, all-steel car that resembled the [[forty-and-eights]] used in Europe during [[World War I]]. The prototype weighed in at 13½ [[ton]]s and was outfitted with a 1,500-[[pound (mass)|pound]] ice bunker at each end. The car was leased to [[Hormel]] and saw service between [[Chicago, Illinois]] and the southern United States. The concept failed to gain acceptance with the big eastern railroads and no additional units were built. | ||

| − | === | + | ====Dry ice==== |

| + | The Santa Fe Refrigerator Despatch (SFRD) briefly experimented with [[dry ice]] as a cooling agent in 1931. The compound was readily-available and seemed like an ideal replacement for frozen water. Dry ice melts at -109 °F / -78.33 °C (versus 32 °F / 0 °C for conventional ice) and was twice as effective thermodynamically. Overall weight was reduced as the need for brine and water was eliminated. While the higher cost of dry ice was certainly a drawback, logistical issues in loading long lines of cars efficiently prevented it from gaining acceptance over conventional ice. Worst of all, it was found that dry ice can adversely affect the color and flavor of certain foods if placed too close to them. | ||

| − | + | ====Hopper cars==== | |

| + | <!-- Deleted image removed: [[Image:Santa Fe Conditionaire Covered Hopper.jpg|thumb|300px|right|ACFX #47633, one of 100 specially-built "Conditionaire" centerflow hoppers operated by the [[Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway]].]] --> | ||

| + | In 1969, the [[Burlington Northern Railroad]] ordered a number of modified [[covered hopper]] cars from [[American Car and Foundry]] for transporting perishable food in bulk. The 55-foot (16.76 m)-long cars were blanketed with a layer of insulation, equipped with roof hatches for loading, and had centerflow openings along the bottom for fast discharge. A mechanical refrigeration unit was installed at each end of the car, where sheet metal ducting forced cool air into the cargo compartments. | ||

| − | + | The units, rated at 100 [[short ton]]s (90.718 [[Tonne|t]]) capacity (more than twice that of the largest conventional refrigerator car of the day) were economical to load and unload, as no secondary packaging was required. Apples, carrots, onions, and potatoes were transported in this manner with some success. Oranges, on the other hand, tended to burst under their own weight, even after wooden baffles were installed to better distribute the load. The Santa Fe Railway leased 100 of the hoppers from ACF, and in April, 1972 purchased 100 new units. The cars' irregular, orange-colored outer surface (though darker than the standard AT&SF yellow-orange used on reefers) tended to collect dirt easily, and proved difficult to clean. Santa Fe eventually relegated the cars to more typical, non-refrigerated applications. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | === Refrigerator cars in Japan === |

| − | + | The first refrigerated cars in Japan entered service in 1908 for fish transport. Many of these cars were equipped with ice bunkers, however the bunkers were not used generally. Fish were packed in wooden or foam polystyrene boxes with crushed ice. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Fruit and meat transportation in refrigerated rail cars was not common in Japan. For fruits and vegetables, ventilator cars were sufficient due to the short distances involved in transportation. Meat required low temperature storage, therefore transportation was by ship, since most major Japanese cities are located along the coast. | |

| − | + | Refrigerator cars suffered heavy damage in [[World War II]], afterwards the occupation forces confiscated many cars for their own use, utilizing the ice bunkers as originally intended. Supplies were landed primarily at [[Yokohama]], and reefer trains ran from the port to US bases around Japan. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | In 1966, [[Japanese National Railways|JNR]] developed "resa 10000" and "remufu 10000" type refrigerated cars that could travel at 100km/h (this was very fast in the sense of Japanese freight trains). They were used in fish freight express trains. "Tobiuo"([[Flying fish]]) train from Shimonoseki to Tokyo, and "Ginrin"(Silver [[Scale (zoology)|scale]]) train from Hakata to Tokyo, were operated. | |

| − | + | By the 1960s, refrigerator trucks had begun to displace railcars. Strikes in the 1970s resulted in the loss of reliability and punctuality, important to fish transportation. In 1986, the last refrigerated cars were replaced by reefer containers. | |

| − | + | Most Japanese reefers were four-wheeled due to the small traffic demands. There were very few bogie wagons in late years. The total number of Japanese reefers numbered approximately 8,100. At their peak, about 5,000 refrigerated cars were operated in the late 1960s. Mechanical refrigerators were tested, but did not see widespread use. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | There were no privately-owned reefers in Japan, as compared to the US. This is because fish transportation were protected by national policies and rates were kept low, and there was little profit in refrigerated car ownership. | |

| − | == | + | ==Timeline== |

| − | + | {{see|Timeline of low-temperature technology}} | |

| − | + | * 1842: The [[Western Railroad of Massachusetts]] experimented with innovative freight car designs capable of carrying all types of perishable goods without spoilage. | |

| + | * 1851: The first refrigerated boxcar entered service on the [[Northern Railroad of New York]]. | ||

| + | * 1857: The first consignment of refrigerated, dressed beef traveled from Chicago to the East Coast in ordinary box cars packed with ice. | ||

| + | * 1866: Horticulturist [[Parker Earle]] shipped strawberries in iced boxes by rail from southern Illinois to Chicago on the [[Illinois Central Railroad]]. | ||

| + | * 1868: William Davis of [[Detroit, Michigan]] developed a refrigerator car cooled by a frozen ice-salt mixture, and patented it in the US. The patent was subsequently sold to George Hammond, a local meat packer who amassed a fortune in refrigerated shipping. | ||

| + | * 1876: German engineer [[Carl von Linde]] developed one of the first mechanical refrigeration systems. | ||

| + | * 1878: Gustavus Swift (along with engineer Andrew Chase) developed the first practical ice-cooled railcar. Soon Swift formed the Swift Refrigerator Line (SRL), the world's first. | ||

| + | * 1880: The first patent for a mechanically-refrigerated railcar issued in the United States was granted to Charles William Cooper. | ||

| + | * 1884: The Santa Fe Refrigerator Despatch (SFRD) was established as a subsidiary of the [[Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway]] to carry perishable commodities. | ||

| + | * 1885: Berries from [[Norfolk, Virginia]] were shipped by refrigerator car to New York. | ||

| + | * 1887 Parker Earle joined F.A. Thomas of Chicago in the fruit shipping business. The company owned 60 ice-cooled railcars by 1888, and 600 by 1891. | ||

| + | * 1888: Armour & Co. shipped beef from Chicago to Florida in a car cooled by [[ethyl chloride]]-compression machinery. [[Florida]] oranges were shipped to New York under refrigeration for the first time. | ||

| + | * 1889: The first cooled shipment of fruit from California was sold on the New York market. | ||

| + | * 1898: [[Russia|Russia's]] first refrigerator cars entered service. The country's inventory w reached 1,900 by 1908, and 3,000 two years later, and peaked at approximately 5,900 by 1916. The cars were utilized mainly for transporting butter from [[Siberia]] to the [[Baltic Sea]], a 12 day journey. | ||

| + | * 1899: Refrigerated fruit traffic within the US reached 90,000 [[short ton]]s per year; Transport from California to NY averaged 12 days in 1900. | ||

| + | * 1901: Carl von Linde equipped a Russian train with a mobile, central mechanical refrigeration plant to distribute cooling to cars carrying perishable goods. Similar systems were used in Russia as late as 1975. | ||

| + | * 1905: U.S. traffic in refrigerated fruit reacheed 430,000 short tons. As refrigerator car designs become standardized, the practice of indicating the "patentee" on the sides was discontinued. | ||

| + | * 1907: The Pacific Fruit Express began operations with more than 6,000 refrigerated cars, transporting fruit and vegetables from Western producers to Eastern consumers. US traffic in refrigerated fruit hit 600,000 short tons. | ||

| + | * 1908: Japan's first refrigerator cars entered service. The cars were for seafood transportation, in the same manner as most other Japanese reefers. | ||

| + | * 1913: The number of thermally-insulated railcars (most of which were cooled by ice) in the U.S. topped 100,000. | ||

| + | * 1920: The Fruit Growers Express (or FGE, a former subsidiary of the Armour Refrigerator Line) was formed using 4,280 reefers acquired from Armour & Co. | ||

| + | * 1923: FGE and the [[Great Northern Railway (U.S.)|Great Northern Railway]] for the Western Fruit Express (WFE) in order to compete with the Pacific Fruit Express and Santa Fe Refrigerator Despatch in the West. | ||

| + | * 1925–1930: Mechanically-refrigerated trucks enter service and gain public acceptance, particularly for the delivery of milk and ice cream. | ||

| + | * 1926: The FGE expanded its service into the Pacific Northwest and the Midwest through the WFE and the Burlington Refrigerator Express Company (BREX), its other partly-owned subsidiary. FGE purchased 2,676 reefers from the [[Pennsylvania Railroad]]. | ||

| + | * 1928: The FGE formed the [[National Car Company]] as a subsidiary to service the meat transportation market. Customers include [[Kahns]], [[Oscar Mayer]], and [[Rath (company)|Rath]]. | ||

| + | * 1930: The number of refrigerator cars in the United States reached its maximum of approximately 183,000. | ||

| + | * 1931: The SFRD reconfigured 7 reefers to utilize dry ice as a cooling agent. | ||

| + | * 1932: [[Japanese Government Railways]] built vehicles specially made for dry ice coolant. | ||

| + | * 1936: The first all-steel reefers entered service. | ||

| + | * 1937: The Interstate Commerce Commission banned "billboard" type advertisements on railroad cars. | ||

| + | * 1946: Two experimental aluminum-body refrigerator cars entered service on the PFE; an experimental reefer with a stainless-steel body was built for the SFRD. | ||

| + | * 1950: The U.S. refrigerator car roster dropped to 127,200. | ||

| + | * 1957: The last ice bunker refrigerator cars were built. | ||

| + | * 1958: The first mechanical reefers (utilizing diesel-powered refrigeration units) entered revenue service. | ||

| + | * 1960s: The flush, "plug" style sliding door was introduced as an option, providing a larger door to ease loading and unloading. The tight-fitting doors were better insulated and allowed the car to be maintained at a more even temperature. | ||

| + | * 1966: [[Japanese National Railways]] started operation of fish freight express trains by newly built "resa 10000" type refers. | ||

| + | * 1969: ACF constructed several experimental center flow hopper cars incorporating mechanical cooling systems and insulated cargo cells. The units were intended for shipment of bulk perishables. | ||

| + | * 1971: The last ice-cooled reefers were retired. | ||

| + | * 1980: The US refrigerator car roster dropped to 80,000. | ||

| + | * 1986: The last reefers in Japan were replaced by [[Reefer (container)|refer containers]]. | ||

| + | * 1990s: The first cryogenically-cooled reefers entered service. | ||

| + | * 2001: The number of refrigerator cars in the United States bottomed out at approximately 8,000. | ||

| + | * 2005: The number of reefers in the United States climbs to approximately 25,000, due to significant new refrigerator car orders. | ||

| − | === | + | ==Specialized applications== |

| − | + | ===Express service=== | |

| + | [[Image:FM-REA-65.jpg|thumb|225px|right|An REA express reefer is positioned at the head end of Santa Fe train No.8, the ''Fast Mail Express'', in 1965.]] | ||

| + | Standard refrigerated transport is often utilized for good with less than 14 days of refrigerated "shelf life": avocados, cut flowers, green leafy vegetables, lettuce, mangos, meat products, mushrooms, peaches and nectarines, pineapples and papayas, sweet cherries, and tomatoes. "Express" reefers are typically employed in the transport of special perishables: commodities with a refrigerated shelf life of less than 7 days such as human blood, fish, [[scallions|green onions]], milk, strawberries, and certain pharmaceuticals. | ||

| − | + | The earliest express-service refrigerator cars entered service around 1890, shortly after the first express train routes were established in North America. The cars did not come into general use until the early 20th century. Most units designed for express service are larger than their standard counterparts, and are typically constructed more along the lines of [[baggage car]]s than freight equipment. Cars must be equipped with speed-rated trucks and brakes, and — if they are to be run ahead of the passenger car consist — must also incorporate an air line for pneumatic braking, a communication signal air line, and a steam line for train heating. Express units were typically painted in passenger car colors, such as [[Pullman Company|Pullman]] green. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The first purpose-built express reefer emerged from the [[Erie Railroad|Erie Railroad's]] Susquehanna Shops on August 1, 1886. By 1927 some 2,218 express cars traveled America's rails, and three years later that number was 3,264. In 1940 private rail lines began to build and operate their own reefers, the [[Railway Express Agency]] (REA) being by far the largest. In 1948 the REA roster (which would continue to expand into the 1950s) numbered approximately 1,800 cars, many of which were [[World War II]] "[[troop sleeper]]s" modified for express refrigerated transport. By 1965, due to a decline in refrigerated traffic, many express reefers were leased to railroads for use as bulk mail carriers. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Image:Pfe722.jpg|thumb|350px|left|Pacific Fruit Express #722, an ice-cooled, express-style refrigerator car designed to carry milk in [[stainless steel]] cans and other highly-perishable cargo at the head end of passenger train consists.]] | |

| − | + | [[Image:REX6687 Troop Reefer.jpg|thumb|400px|right|Railway Express Agency refrigerator car #6687, a converted World War II "troop sleeper." Note the square panels along the sides that cover the window openings.]] | |

| + | <br style="clear:both;"> | ||

| − | + | ===Intermodal=== | |

| + | [[Image:Vonsvans01022.jpg|thumb|300px|right|An intermodal train containing mechanically-cooled [[Semi-trailer|highway trailers]] in "[[piggy-back|piggyback]]" service passes through the [[Cajon Pass]] in February, 1995.]] | ||

| − | + | For many years, virtually all of the perishable traffic in the United States was carried by the railroads. While railroads were subject to government regulation regarding shipping rates, trucking companies could set their own rate for hauling agricultural products, giving them a competitive edge. In March 1979 the [[Interstate Commerce Commission|ICC]] exempted rail transportation of fresh fruits and vegetables from all economic regulation. Once the "Agricultural Exemption Clause" was removed from the ''Interstate Commerce Act'', railroads began aggressively pursuing trailer-on-flatcar (TOFC) business (a form of [[intermodal freight transport]]) for refrigerated trailers. Taking this one step further, a number of carriers (including the PFE and SFRD) purchased their own refrigerated trailers to compete with interstate trucks. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The final chapter has not, as many have predicted, been written for the refrigerator car in America. The dawn of the 21st century has seen the first significant reefer orders since the early 1970s. | |

| − | === | + | ===Tropicana "Juice Train"=== |

| − | + | {{main|Juice Train}} | |

| − | + | [[Image:TPIX 250.JPG|thumb|250px|Former Tropicana refrigerator car, shortly after being donated to the [[Florida Gulf Coast Railroad Museum]] -- [[Palmetto, Florida]].]] | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In 1970 Tropicana orange juice was shipped in bulk via [[Thermal insulation|insulated]] [[boxcars]] in one weekly round-trip from [[Bradenton, Florida]] to [[Kearny, New Jersey]]. By the following year, the company was operating two 60-car unit trains a week, each carrying around 1 million U.S. [[gallon]]s (4 million [[litre|liters]]) of juice. On June 7, 1971 the "Great White Juice Train" (the first unit train in the food industry, consisting of 150 one hundred [[short ton]] insulated boxcars fabricated in the [[Alexandria, Virginia]] shops of [[Fruit Growers Express]]) commenced service over the 1,250-mile (2,000-kilometer) route. An additional 100 cars were soon added, and small mechanical refrigeration units were installed to keep temperatures constant. Tropicana saved $40 million in fuel costs during the first ten years in operation. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | == | + | ==AAR classifications== |

| − | + | {| class="toccolours" | |

| − | {| class=" | + | |- |

| − | |+ | + | |+ [[Association of American Railroads|AAR]] classifications of refrigerator car types<ref>''The Great Yellow Fleet'', p 126.</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | ! | + | ! bgcolor=#cc9966 | Class |

| + | ! bgcolor=#cc9966 | Description | ||

| + | ! bgcolor=#cc9966 | Class | ||

| + | ! bgcolor=#cc9966 | Description | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |align=left | '''RA |

| + | |align=left | Brine-tank ice bunkers | ||

| + | |align=left | '''RPB | ||

| + | |align=left | Mechanical refrigerator with electro-mechanical axle drive | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |align=left | '''RAM |

| + | |align=left | Brine-tank ice bunkers with beef rails | ||

| + | |align=left | '''RPL | ||

| + | |align=left | Mechanical refrigerator with loading devices | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |align=left | '''RAMH |

| + | |align=left | Brine-tank with beef rails and heaters | ||

| + | |align=left | '''RPM | ||

| + | |align=left | Mechanical refrigerator with beef rails | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |align=left | '''RB |

| + | |align=left | No ice bunkers — heavy insulation | ||

| + | |align=left | '''RS | ||

| + | |align=left | Bunker refrigerator — common ice bunker car | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |align=left | '''RBL |

| + | |align=left | No ice bunkers and loading devices | ||

| + | |align=left | '''RSB | ||

| + | |align=left | Bunker refrigerator — air fans and loading devices | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |align=left | '''RBH |

| + | |align=left | No ice bunkers — gas heaters | ||

| + | |align=left | '''RSM | ||

| + | |align=left | Bunker refrigerator with beef rails | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |align=left | '''RBLH |

| + | |align=left | No ice bunkers — loading devices and heaters | ||

| + | |align=left | '''RSMH | ||

| + | |align=left | Bunker refrigerator with beef rails and heaters | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |align=left | '''RCD |

| + | |align=left | Solid carbon-dioxide refrigerator | ||

| + | |align=left | '''RSTC | ||

| + | |align=left | Bunker refrigerator — electric air fans | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |align=left | '''RLO |

| + | |align=left | Special car type — permanently-enclosed (covered hopper type) | ||

| + | |align=left | '''RSTM | ||

| + | |align=left | Bunker refrigerator — electric air fans and beef rails | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | |align=left | '''RP |

| + | |align=left | Mechanical refrigerator | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | Note: '''Class B''' refrigerator cars are those designed for passenger service; insulated boxcars are designated '''Class L'''. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==Notes== |

| − | + | <references/> | |

| − | == | + | ==References== |

| − | + | * Boyle, Elizabeth and Rodolfo Estrada. (1994) [http://www.oznet.ksu.edu/meatscience/column/industry.htm/ "Development of the U.S. Meat Industry"] — Kansas State University Department of Animal Sciences and Industry. | |

| − | * | + | * Hendrickson, Richard and Richard E. Scholz. (1986). "Reefer car 13000: a postmortem." ''The Santa Fé Route'' '''IV''' (2) 8. |

| + | * {{cite book|author=Hendrickson, Richard H.|year=1998|title=Santa Fe Railway Painting and Lettering Guide for Model Railroaders, Volume 1: Rolling Stock|publisher=The Santa Fe Railway Historical and Modeling Society, Inc., Highlands Ranch, CO|id=}} | ||

| + | * Pearce, Bill. (2005). "Express Reefer from troop sleeper in N." ''Model Railroader'' '''72''' (12) 62–65. | ||

| + | * [http://users2.ev1.net/~jssand/SFHMS/Sand/SFRD/5.htm Reefer Operations on Model Railroads with an emphasis on the ATSF] April 15, 2005 article at [http://www.atsfrr.net/ The Santa Fe Railway Historical & Modeling Society] official website — accessed on November 7, 2005. | ||

| + | * Thompson, Anthony W. et al. (1992). ''Pacific Fruit Express''. Signature Press, Wilton, CA. ISBN 1-930013-03-5. | ||

| + | * White, John H. (1986). ''The Great Yellow Fleet''. Golden West Books, San Marino, CA. ISBN 0-87095-091-6. | ||

| + | * White, Jr., John H. (1993). ''The American Railroad Freight Car''. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland. ISBN 0-8018-5236-6. | ||

| − | + | ==See also== | |

| − | + | * [[Refrigeration]] | |

| − | + | * [[Reefer (ship)]] | |

| − | + | * [[Reefer (container)]] | |

| − | + | * [[Refrigerated transport Dewar]] | |

| − | + | * [[Refrigerator truck]] | |

| − | + | * [[Cold chain]] | |

| − | |||

| − | == See also == | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * [[ | ||

| − | * [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * [[ | ||

| − | * [[ | ||

| − | * [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==External links== |

| − | + | * [http://www.sdrm.org/roster/freight/ref21335/index.html Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe Railway #21335] — photo and short history of a steel-sheathed "billboard" car. | |

| − | ; | + | * [http://www.sdrm.org/stories/reefer/ "Coast to Coast"] article by Richard Hendrickson at the [http://www.sdrm.org/ Pacific Southwest Railway Museum] official website. |

| − | * | + | * [http://www.csrmf.org/doc.asp?id=185 Fruit Growers Express Company #35832] — photos and short history of an example of the wooden ice-type "reefers" commonly placed in service between 1920 and 1940. |

| − | * | + | * [http://www.sdrm.org/roster/freight/ref56415/index.html Fruit Growers Express Company #56415] — photos and short history of an example of the wooden ice-type "reefers" used in the first half of the 20th century for shipping produce. |

| − | * | + | * [http://www.sdrm.org/roster/freight/ref11207/index.html Pacific Fruit Express Company #11207] — photo and short history of one of the last ice-type refrigerator cars built. |

| − | * | + | * [http://www.sdrm.org/roster/freight/re300010/index.html Pacific Fruit Express Company #300010] — photo and short history of one of the first mechanical-type refrigerator cars built. |

| − | * | + | * [http://www.uprr.com/aboutup/photos/pfe/index.shtml Pacific Fruit Express photo gallery] at the [[Union Pacific Railroad]] official website. |

| + | * [http://www.containerserviceco.com Container Service Co.] official website; contains pictures of cryogenic railcars and ocean freight containers. | ||

| − | + | {{Refrigerator Car Lines of the United States}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Freight cars}} | {{Freight cars}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Cooling technology]] |

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Food preservation]] |

| + | [[Category:Freight equipment]] | ||

| − | + | [[de:Kühlwagen (Eisenbahn)]] | |

| − | + | [[eo:Malvarmiguja vagono]] | |

| − | + | [[ja:冷蔵車]] | |

| − | [[de: | + | [[ru:Изотермический вагон]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[eo: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ja: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ru: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Revision as of 01:43, 1 December 2008

A refrigerator car (or "reefer") is a refrigerated boxcar, a piece of railroad rolling stock designed to carry perishable freight at specific temperatures. Refrigerator cars differ from simple insulated boxcars and ventilated boxcars (commonly used for transporting fruit), neither of which are fitted with cooling apparatus. Reefers can be ice-cooled, come equipped with any one of a variety of mechanical refrigeration systems, or utilize carbon dioxide (either as dry ice, or in liquid form) as a cooling agent. Milk cars (and other types of "express" reefers) may or may not include a cooling system, but are equipped with high-speed trucks and other modifications that allow them to travel with passenger trains.

Reefer applications can be divided into five broad groups: 1) dairy and poultry producers require refrigeration and special interior racks; 2) fruit and vegetable reefers tend to see seasonal use, and are generally used for long-distance shipping (for some shipments, only ventilation is necessary to remove the heat created by the ripening process); 3) manufactured foods (such as canned goods and candy) as well as beer and wine do not require refrigeration, but do need the protection of an insulated car; 4) meat reefers come equipped with specialized beef rails for handling sides of meat, and brine-tank refrigeration to provide lower temperatures (most of these units are either owned or leased by meat packing firms); and 5) fish and seafoods are transported, packed in wooden or foam polystyrene box with crushed ice, and ice bunkers are not used generally.

History

Background

After the end of the American Civil War, Chicago, Illinois emerged as a major railway center for the distribution of livestock raised on the Great Plains to Eastern markets.& Getting the animals to market required herds to be driven up to 1,200 miles (2,000 km) to railheads in Kansas City, Missouri, where they were loaded into specialized stock cars and transported live ("on-the-hoof") to regional processing centers. Driving cattle across the plains also caused tremendous weight loss, with some animals dying in transit.

Upon arrival at the local processing facility, livestock were either slaughtered by wholesalers and delivered fresh to nearby butcher shops for retail sale, smoked, or packed for shipment in barrels of salt. Costly inefficiencies were inherent in transporting live animals by rail, particularly the fact that about sixty percent of the animal's mass is inedible. The death of animals weakened by the long drive further increased the per-unit shipping cost. Meat packer Gustavus Swift sought a way to ship dressed meats from his Chicago packing plant to eastern markets.

Early attempts at refrigerated transport

Attempts were made during the mid-1800s to ship agricultural products by rail. As early as 1842, the Western Railroad of Massachusetts was reported in the June 15 edition of the Boston Traveler to be experimenting with innovative freight car designs capable of carrying all types of perishable goods without spoilage.& The first refrigerated boxcar entered service in June 1851, on the Northern Railroad of New York (or NRNY, which later became part of the Rutland Railroad). This "icebox on wheels" was a limited success since it was only functional in cold weather. That same year, the Ogdensburg and Lake Champlain Railroad (O&LC) began shipping butter to Boston in purpose-built freight cars, utilizing ice for cooling.

The first consignment of dressed beef left the Chicago stock yards in 1857 in ordinary boxcars retrofitted with bins filled with ice. Placing meat directly against ice resulted in discoloration and affected the taste, and proved impractical. During the same period Swift experimented by moving cut meat using a string of ten boxcars with their doors removed, and made a few test shipments to New York during the winter months over the Grand Trunk Railway (GTR). The method proved too limited to be practical.

Detroit's William Davis patented a refrigerator car that employed metal racks to suspend the carcasses above a frozen mixture of ice and salt. He sold the design in 1868 to George H. Hammond, a Detroit meat packer, who built a set of cars to transport his products to Boston using ice from the Great Lakes for cooling.& The load had the tendency of swinging to one side when the car entered a curve at high speed, and use of the units was discontinued after several derailments. In 1878 Swift hired engineer Andrew Chase to design a ventilated car that was well insulated, and positioned the ice in a compartment at the top of the car, allowing the chilled air to flow naturally downward.& The meat was packed tightly at the bottom of the car to keep the center of gravity low and to prevent the cargo from shifting. Chase's design proved to be a practical solution to providing temperature-controlled carriage of dressed meats, and allowed Swift and Company to ship their products across the United States and internationally.

Swift's attempts to sell Chase's design to major railroads were rebuffed, as the companies feared that they would jeopardize their considerable investments in stock cars, animal pens, and feedlots if refrigerated meat transport gained wide acceptance. In response, Swift financed the initial production run on his own, then — when the American roads refused his business — he contracted with the GTR (a railroad that derived little income from transporting live cattle) to haul the cars into Michigan and then eastward through Canada. In 1880 the Peninsular Car Company (subsequently purchased by ACF) delivered the first of these units to Swift, and the Swift Refrigerator Line (SRL) was created. Within a year the Line’s roster had risen to nearly 200 units, and Swift was transporting an average of 3,000 carcasses a week to Boston, Massachusetts. Competing firms such as Armour and Company quickly followed suit. By 1920 the SRL owned and operated 7,000 of the ice-cooled rail cars. The General American Transportation Corporation would assume ownership of the line in 1930.

Live cattle and dressed beef deliveries to New York (short tons):

| (Stock Cars) | (Refrigerator Cars) | |

| Year | Live Cattle | Dressed Beef |

| 1882 | 366,487 | 2,633 |

| 1883 | 392,095 | 16,365 |

| 1884 | 328,220 | 34,956 |

| 1885 | 337,820 | 53,344 |

| 1886 | 280,184 | 69,769 |

The subject cars travelled on the Erie, Lackawanna, New York Central, and Pennsylvania railroads.

Source: Railway Review, January 29, 1887, p. 62.

19th Century American Refrigerator Cars:

| Year | Private Lines | Railroads | Total |

| 1880 | 1,000 est. | 310 | 1,310 est. |

| 1885 | 5,010 est. | 990 | 6,000 est. |

| 1890 | 15,000 est. | 8,570 | 23,570 est. |

| 1895 | 21,000 est | 7,040 | 28,040 est. |

| 1900 | 54,000 est. | 14,500 | 68,500 est. |

Source: Poor's Manual of Railroads and ICC and U.S. Census reports.

The "Ice Age"

The use of ice to refrigerate and thus preserve food dates back to prehistoric times. Through the ages, the seasonal harvesting of snow and ice was a regular practice of many cultures. China, Greece, and Rome stored ice and snow in caves or dugouts lined with straw or other insulating materials. Rationing of the ice allowed the preservation of foods during hot periods, a practice that was successfully employed for centuries. For most of the 1800s, natural ice (harvested from ponds and lakes) was used to supply refrigerator cars. At high altitudes or northern latitudes, one foot tanks were often filled with water and allowed to freeze. Ice was typically cut into blocks during the winter and stored in insulated warehouses for later use, with sawdust and hay packed around the ice blocks to provide additional insulation. A late-19th century wood-bodied reefer required reicing every 250 to Template:Convert.

By the turn of the 20th century manufactured ice became more common. The Pacific Fruit Express (PFE), for example, maintained 7 natural harvesting facilities, and operated 18 artificial ice plants. Their largest plant (located in Roseville, California) produced 1,200 short tons of ice daily, and Roseville’s docks could accommodate up to 254 cars. At the industry’s peak, 13 million short tons of ice was produced for refrigerator car use annually.

"Top Icing"

Top icing is the practice of placing a 2 to Template:Convert layer of crushed ice on top of agricultural products that have high respiration rates, need high relative humidity, and benefit from having the cooling agent sit directly atop the load (or within individual boxes). Cars with pre-cooled fresh produce were top iced just before shipment. Top icing added considerable dead weight to the load. Top-icing a Template:Convert reefer required in over 10,000 pounds of ice. It had been postulated that as the ice melts, the resulting chilled water would trickle down through the load to continue the cooling process. It was found, however, that top-icing only benefited the uppermost layers of the cargo, and that the water from the melting ice often passed through spaces between the cartons and pallets with little or no cooling effect. It was ultimately determined that top-icing is useful only in preventing an increase in temperature, and was eventually discontinued.

Men harvest ice on Michigan's Lake Saint Clair, circa 1905. The ice was cut into blocks and hauled by wagon to a cold storage warehouse, and held until needed.

- Mechanical Ice Loader.jpg

The "business end" of a mechanical ice loading system services a line of Pacific Fruit Express refrigerator cars. Each car will require approximately 5½ short tons (5 metric tons) of ice.

The typical service cycle for an ice-cooled produce reefer (generally handled as a part of a block of cars):

- The cars were cleaned with hot water or steam.

- Depending on the cargo, the cars might have undergone 4 hours of "pre-cooling" prior to loading, which entailed blowing in cold air through one ice hatch and allowing the warmer air to be expelled through the other hatches. The practice, dating back almost to the inception of the refrigerator car, saved ice and resulted in fresher cargo.

- The cars' ice bunkers were filled, either manually from an icing dock, via mechanical loading equipment, or (in locations where demand for ice was sporadic) using specially-designed field icing cars.

- The cars were delivered to the shipper for loading, and the ice was topped-off.

- Depending on the cargo and destination, the cars may have been fumigated.

- The train would depart for the eastern markets.

- The cars were reiced in transit approximately once a day.

- Upon reaching their destination, the cars were unloaded.

- If in demand, the cars would be returned to their point of origin empty. If not in demand, the cars would be cleaned and possibly used for a dry shipment.

- Tiffany RRG 1877.jpg

This engraving of Tiffany’s original "Summer and Winter Car" appeared in the Railroad Gazette just before Joel Tiffany received his refrigerator car patent in July, 1877. Tiffany's design mounted the ice tank in a clerestory atop the car's roof, and relied on a train's motion to circulate cool air throughout the cargo space.

- Reefers-shorty-Armour-Kansas-City-3891-Pullman.jpg

A Pullman-built "shorty" reefer bears the Armour Packing Co. · Kansas City logo, circa 1885. The name of the "patentee" was displayed on the car's exterior, a practice intended to "...impress the shipper and intimidate the competition...," even though most patents covered trivial or already-established design concepts.

- Reefers-shorty-ATSF-CM-type-1898-cyc ACF builders photo.jpg

A rare double-door refrigerator car utilized the "Hanrahan System of Automatic Refrigeration" as built by ACF, circa 1898. The car had a single, centrally located ice bunker which was said to offer better cold air distribution. The two segregated cold rooms were well suited for less-than-carload (LCL) shipments.

A pre-1911 "shorty" reefer bears an advertisement for Anheuser-Busch's Malt Nutrine tonic. The use of similar "billboard" advertising on freight cars was banned by the Interstate Commerce Commission in 1937, and thereafter cars so decorated could no longer be accepted for interchange between roads.

Refrigerator cars required effective insulation to protect their contents from temperature extremes. "Hairfelt" derived from compressed cattle hair, sandwiched into the floor and walls of the car, was inexpensive but flawed — over its three- to four-year service life it would decay, rotting out the car's wooden partitions and tainting the cargo with a foul odor. The higher cost of other materials such as "Linofelt" (woven from flax fibers) or cork prevented their widespread adoption. Synthetic materials such as fiberglass and polystyrene, both introduced after World War II, offered the most cost-effective and practical solution.

Mechanical refrigeration

In the latter half of the 20th century mechanical refrigeration began to replace ice-based systems. In time, mechanical refrigeration units replaced the "armies" of personnel required to re-ice the cars. The "plug" door was introduced experimentally by P.F.E. (Pacific Fruit Express) in April 1947, when one of their R-40-10 series cars, #42626, was equipped with one. P.F.E.'s R-40-26 series reefers, designed in 1949 and built in 1951, were the first production series cars to be so equipped. In addition, the Santa Fe Railroad first used plug doors on their SFRD RR-47 series cars, which were also built in 1951. This type of door, provided a larger six foot opening, to facilitate car loading and unloading. These tight-fitting doors were better insulated and could maintain a more even temperature inside the car. By the mid-1970s the few remaining ice bunker cars were relegated to "top-ice" service, where crushed ice was applied atop the commodity.

- Cutaway PFE mechanical.jpg

A cutaway illustration of a conventional mechanical refrigerator car, which typically contains in excess of 800 moving parts.

- ARMN 110386 detail photo by JS Rybak @ Clarke Ontario Canada April 2005.jpg

State-of-the-art mechanical refrigerator car designs place the removable, end-mounted refrigeration unit outside of the freight compartment in order to facilitate access for servicing or replacement.

- Amtk74049.jpg

A modern mechanical refrigerator car, outfitted for high-speed service, bears the colors and markings of Amtrak Express, Amtrak's freight and shipping service.

Cryogenic refrigeration

The Topeka, Kansas shops of the Santa Fe Railway built five experimental refrigerator cars employing liquid nitrogen as the cooling agent in 1965. A mist of liquified nitrogen was released throughout the car if the temperature rose above a pre-determined level. Each car carried 3,000 pounds (1,360 kg) of refrigerant and could maintain a temperature of minus 20 degrees Fahrenheit (−30 °C). During the 1990s, a few railcar manufacturers experimented with the use of liquid carbon dioxide (CO2) as a cooling agent. The move was in response to rising fuel costs, and was an attempt to eliminate the standard mechanical refrigeration systems that required periodic maintenance. The CO2 system can keep the cargo frozen solid as long as 14 to 16 days.

Several hundred "cryogenic" refrigerator cars were placed in service transporting frozen foodstuffs, though they failed to gain wide acceptance (due, in part, to the rising cost of liquid carbon dioxide). Since cryogenic refrigeration is a proven technology and environmentally friendly, the rising price of fuel and the increased availability of carbon dioxide from Kyoto Protocol-induced capturing techniques may lead to a resurgence in cryogenic railcar usage. Cryo-Trans, Inc. (founded in 1985) has since dedicated 200 of its refrigerated cars to wine transportation service.

Experimentation

Aluminum and stainless steel

In 1946, the Pacific Fruit Express procured from the Consolidated Steel Corporation of Wilmington, California two Template:Convert aluminum-bodied ventilator refrigerator cars, to compare the durability of the lightweight alloy versus that of steel. It was hoped that weight savings (the units weighed almost 10,000 pounds less than a like-sized all-steel car) and better corrosion resistance would offset the higher initial cost. One of the aluminum car bodies was manufactured by Alcoa (PFE #44739), while the other was built by the Reynolds Aluminum Company (PFE #45698).

The cars (outfitted with state-of-the-art fiberglass insulation and axle-driven fans for internal air circulation) traveled throughout the Southern Pacific and Union Pacific systems, where they were displayed to promote PFE's post-World War II modernization. Though both units remained in service over 15 years (#45698 was destroyed in a wreck in May 1962, while #44739 was scrapped in 1966), no additional aluminum reefers were constructed, cost being the likely reason. Also in 1946 the Consolidated Steel delivered the world's only reefer to have a stainless steel body to the Santa Fe Refrigerator Despatch. The Template:Convert car was equipped with convertible ice bunkers, side ventilation ducts, and axle-driven circulation fans. It was thought that stainless steel would better resist the corrosive deterioration resulting from salting the ice. The one-of-a-kind unit entered service as #13000, but was subsequently redesignated as #1300, and later given #4150 in 1955.&

#4150 spent most of its life in express service. Cost was cited as the reason no additional units were ordered. The car was dismantled at Clovis, New Mexico in February, 1964.

"Depression Baby"

During the 1930s, the North American Car Company produced a one-of-a-kind, four-wheeled ice bunker reefer intended to serve the needs of specialized shippers who did not generate sufficient product to fill a full-sized refrigerator car. NADX #10000 was a 22-foot-long, all-steel car that resembled the forty-and-eights used in Europe during World War I. The prototype weighed in at 13½ tons and was outfitted with a 1,500-pound ice bunker at each end. The car was leased to Hormel and saw service between Chicago, Illinois and the southern United States. The concept failed to gain acceptance with the big eastern railroads and no additional units were built.

Dry ice

The Santa Fe Refrigerator Despatch (SFRD) briefly experimented with dry ice as a cooling agent in 1931. The compound was readily-available and seemed like an ideal replacement for frozen water. Dry ice melts at -109 °F / -78.33 °C (versus 32 °F / 0 °C for conventional ice) and was twice as effective thermodynamically. Overall weight was reduced as the need for brine and water was eliminated. While the higher cost of dry ice was certainly a drawback, logistical issues in loading long lines of cars efficiently prevented it from gaining acceptance over conventional ice. Worst of all, it was found that dry ice can adversely affect the color and flavor of certain foods if placed too close to them.

Hopper cars

In 1969, the Burlington Northern Railroad ordered a number of modified covered hopper cars from American Car and Foundry for transporting perishable food in bulk. The 55-foot (16.76 m)-long cars were blanketed with a layer of insulation, equipped with roof hatches for loading, and had centerflow openings along the bottom for fast discharge. A mechanical refrigeration unit was installed at each end of the car, where sheet metal ducting forced cool air into the cargo compartments.

The units, rated at 100 short tons (90.718 t) capacity (more than twice that of the largest conventional refrigerator car of the day) were economical to load and unload, as no secondary packaging was required. Apples, carrots, onions, and potatoes were transported in this manner with some success. Oranges, on the other hand, tended to burst under their own weight, even after wooden baffles were installed to better distribute the load. The Santa Fe Railway leased 100 of the hoppers from ACF, and in April, 1972 purchased 100 new units. The cars' irregular, orange-colored outer surface (though darker than the standard AT&SF yellow-orange used on reefers) tended to collect dirt easily, and proved difficult to clean. Santa Fe eventually relegated the cars to more typical, non-refrigerated applications.

Refrigerator cars in Japan

The first refrigerated cars in Japan entered service in 1908 for fish transport. Many of these cars were equipped with ice bunkers, however the bunkers were not used generally. Fish were packed in wooden or foam polystyrene boxes with crushed ice.

Fruit and meat transportation in refrigerated rail cars was not common in Japan. For fruits and vegetables, ventilator cars were sufficient due to the short distances involved in transportation. Meat required low temperature storage, therefore transportation was by ship, since most major Japanese cities are located along the coast.

Refrigerator cars suffered heavy damage in World War II, afterwards the occupation forces confiscated many cars for their own use, utilizing the ice bunkers as originally intended. Supplies were landed primarily at Yokohama, and reefer trains ran from the port to US bases around Japan.

In 1966, JNR developed "resa 10000" and "remufu 10000" type refrigerated cars that could travel at 100km/h (this was very fast in the sense of Japanese freight trains). They were used in fish freight express trains. "Tobiuo"(Flying fish) train from Shimonoseki to Tokyo, and "Ginrin"(Silver scale) train from Hakata to Tokyo, were operated.

By the 1960s, refrigerator trucks had begun to displace railcars. Strikes in the 1970s resulted in the loss of reliability and punctuality, important to fish transportation. In 1986, the last refrigerated cars were replaced by reefer containers.

Most Japanese reefers were four-wheeled due to the small traffic demands. There were very few bogie wagons in late years. The total number of Japanese reefers numbered approximately 8,100. At their peak, about 5,000 refrigerated cars were operated in the late 1960s. Mechanical refrigerators were tested, but did not see widespread use.

There were no privately-owned reefers in Japan, as compared to the US. This is because fish transportation were protected by national policies and rates were kept low, and there was little profit in refrigerated car ownership.

Timeline

- 1842: The Western Railroad of Massachusetts experimented with innovative freight car designs capable of carrying all types of perishable goods without spoilage.

- 1851: The first refrigerated boxcar entered service on the Northern Railroad of New York.

- 1857: The first consignment of refrigerated, dressed beef traveled from Chicago to the East Coast in ordinary box cars packed with ice.

- 1866: Horticulturist Parker Earle shipped strawberries in iced boxes by rail from southern Illinois to Chicago on the Illinois Central Railroad.

- 1868: William Davis of Detroit, Michigan developed a refrigerator car cooled by a frozen ice-salt mixture, and patented it in the US. The patent was subsequently sold to George Hammond, a local meat packer who amassed a fortune in refrigerated shipping.

- 1876: German engineer Carl von Linde developed one of the first mechanical refrigeration systems.

- 1878: Gustavus Swift (along with engineer Andrew Chase) developed the first practical ice-cooled railcar. Soon Swift formed the Swift Refrigerator Line (SRL), the world's first.

- 1880: The first patent for a mechanically-refrigerated railcar issued in the United States was granted to Charles William Cooper.

- 1884: The Santa Fe Refrigerator Despatch (SFRD) was established as a subsidiary of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway to carry perishable commodities.

- 1885: Berries from Norfolk, Virginia were shipped by refrigerator car to New York.