Difference between revisions of "Field Guide/Birds/Eastern US and Canada"

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

{{:Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/Gray Catbird}} | {{:Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/Gray Catbird}} | ||

| − | {{: | + | {{:Field Guide/Birds/Molothrus ater}} |

===Piciformes (woodpeckers) === | ===Piciformes (woodpeckers) === | ||

Revision as of 00:22, 14 October 2010

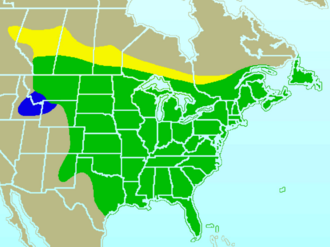

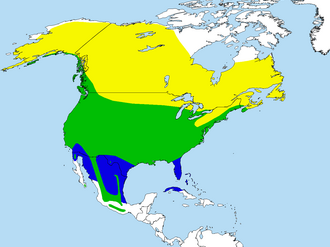

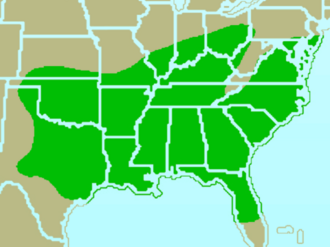

The range maps presented here are color-coded, with yellow indicating the summer range, blue indicating the winter range, and green indicating the year-round range. Some of the range maps do not follow this color code, but it is not difficult to decode them.

Passerine (perching birds)

| Cardinalidae (Cardinal) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| These are robust, seed-eating birds, with strong bills. They are typically associated with open woodland. The sexes usually have distinctive appearances; the family is named for the red plumage (like that of a Catholic cardinal's vestments) of males of the type species, the Northern Cardinal. | |

| Cyanocitta cristata (Blue Jay) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The Blue Jay is a bird with predominantly lavender-blue to mid-blue feathering from the top of the head to midway down the back. There is a pronounced crest on the head. The color changes to black, sky-blue and white barring on the wing primaries and the tail. The bird has an off-white underside, with a black collar around the neck and sides of the head and a white face. Its food is sought both on the ground and in trees and includes virtually all known types of plant and animal sources, such as acorns and beech mast, weed seeds, grain, fruits and other berries, peanuts, bread, meat, eggs and nestlings, small invertebrates of many types, scraps in town parks and bird-table food. | |

| Mimus polyglottos (Northern Mockingbird) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The Northern Mockingbird builds a twig nest in a dense shrub or tree, which it aggressively defends against other birds and animals, including humans. When a predator is persistent, Mockingbirds from neighboring territories, summoned by a distinct call, may join the attack. Other birds may gather to watch as the Mockingbirds harass the intruder. This bird is mainly a permanent resident, but northern birds may move south during harsh weather. Mockingbirds have a strong preference for certain trees such as maple, sweetgum, and sycamore. They generally avoid pine trees after the other trees have grown their leaves. Also, they have a particular preference for high places, such as the topmost branches of trees. Although many species of bird imitate other birds, the Northern Mockingbird is the best known in North America for doing so. It not only imitates birds but also other animals and mechanical sounds. | |

| Turdus migratorius (American Robin) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The American Robin has gray upperparts and head, and orange underparts, usually brighter in the male. Robins are frequently seen running across lawns, picking up earthworms by sight. In fact, the running and stopping behavior is a distinguishing characteristic. When stopping, they are believed to be listening for the movement of prey. | |

| Baeolophus bicolor (Tufted Titmouse) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| These birds have grey upperparts and white underparts with a white face, a grey crest, a dark forehead and a short stout bill; they have rust-colored flanks. The male and female have identical plumage. | |

| Poecile (Chickadee) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| Adults have a black cap and bib with white sides to the face. Their underparts are white with rusty brown on the flanks; their back is grey. They have a short dark bill, short wings and a moderately long tail. There are two types of Chickadee; the Carolina Chickadee, and the Black-capped Chickadee. Carolina Chickadees are so similar to Black-capped Chickadees that they themselves have trouble telling their species apart. Because of this they sometimes mate producing hybrids. The most obvious difference between the three chickadees is that the Carolina Chickadee sings four-note song, Black-capped ones sing two-note songs, and the hybrids sing three-note songs. The song of the Black-capped is a simple, clear whistle of two notes, identical in rhythm, the first roughly a whole-step below the second. This is distinguished from the Carolina chickadee's four-note call fee-bee fee-bay; the lower notes are nearly identical but the higher fee notes are omitted, making the Black-capped song like bee bay. | |

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/White-breasted Nuthatch

| Sialia (Bluebird) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| These are one of the relatively few thrush genera to be restricted to the Americas. As the name implies, these are attractive birds with blue, or blue and red, plumage. Female birds are less brightly colored than males, although color patterns are similar and there is no noticeable difference in size between sexes. There are three species of bluebird; the Eastern Bluebird, the Mountain Bluebird, and the Western Bluebird. The Western Bluebird is very similar to the Eastern Bluebird in appearance. | |

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/Redwinged Blackbird

| Corvus brachyrhynchos (American Crow) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The American Crowis a common bird found throughout North America. Entirely black, it is an easily recognized bird.

The American Crow is a distinctive bird with iridescent black feathers. Its legs, feet and bill are also black. Several regional forms are recognized and differ in bill proportion and overall size from each other across North America, generally being smallest in the southeast and the far west. Averaging 18 inches (46 cm) in length, it is smaller than the Common Raven. American Crows have a lifespan of 7 to 8 years. Captive birds are known to have lived up to 30 years. The most usual call is a loud, short, and rapid "caah-caah-caah". Usually, the birds thrust their heads up and down as they utter this call. American Crows can also produce a wide variety of sounds and sometimes mimic noises made by other animals, including other birds. Crows live in virtually all types of country from wilderness, farmland, parks, open woodland to towns and major cities. The crow is generally a permanent resident, but many birds in the northern parts of the range migrate short distances southward. Outside of the nesting season, these birds often gather in large communal roosts at night. American Crows are protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. The American Crow is omnivorous. It will feed on invertebrates of all types, carrion, scraps of human food, seeds, eggs and nestlings, stranded fish on the shore and various grains. American Crows are active hunters and will prey on mice, frogs, and other small animals. In winter and autumn, the diet of American Crows is more dependent on nuts and acorns. Occasionally, they will visit bird feeders. Like most crows, they will scavenge at rubbish dumps, scattering garbage in the process. Where available, corn, wheat and other agricultural crops are a favorite food. These habits have historically caused the American Crow to be considered a nuisance. However, it is suspected that the harm to crops is offset by the service the American Crow provides by eating insect pests. American Crows are monogamous cooperative breeding birds. Mated pairs form large families of up to 15 individuals from several breeding seasons that remain together for many years. Offspring from a previous nesting season will usually remain with the family to assist in rearing new nestlings. American Crows do not reach breeding age for at least two years. Most do not leave the nest to breed for four to five years. American Crows build bulky stick nests, nearly always in trees but sometimes also in large bushes and, very rarely, on the ground. They will nest in a wide variety of trees, including large conifers, although oaks are most often used. Three to six eggs are laid and incubated for 18 days. The young are fledged usually by about 35 days. Despite attempts by humans in some areas to drive away or eliminate these birds, they remain widespread and very common. The number of individual American Crows is estimated by Birdlife International to be around 31,000,000. The large population, as well as its vast range, are the reasons why the American Crow is considered to be of least concern, meaning that the species is not at immediate risk. | |

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/Common Grackle

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/Gray Catbird

| Molothrus ater (Brown-headed Cowbird) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| Adults have a short finch-like bill and dark eyes. The adult male is mainly iridescent black with a brown head. The adult female is grey with a pale throat and fine streaking on the underparts.

Breeding in open or semi-open country across most of North America, this bird is a brood parasite: it lays its eggs in the nests of other small perching birds, particularly those that build cup-like nests, such as the Yellow Warbler. The young cowbird is fed by the host parents at the expense of their own young. Brown-headed Cowbirds are permanent residents in the southern parts of their range; northern birds migrate to the southern United States and Mexico. They often travel in flocks, sometimes mixed with Red-winged Blackbirds or European Starlings. These birds forage on the ground, often following grazing animals such as horses and cows to catch insects stirred up by the larger animals. They mainly eat seeds and insects. At one time, the Brown-headed Cowbird followed the bison herds across the prairies. Their parasitic nesting behavior complemented this nomadic lifestyle. Their numbers expanded with the clearing of forested areas and the introduction of new grazing animals by settlers across North America. Brown-headed Cowbirds are now commonly seen at suburban birdfeeders. Brown-headed Cowbird females can lay 36 eggs in a season. Over 140 different species of birds are known to have raised young cowbirds. Host parents may sometimes notice the cowbird egg. Different species react in different ways. Gray Catbirds destroy the egg by pecking it. Some species may simply build a new layer over the bottom of the original nest. Brown-headed cowbird nestlings are sometimes expelled from the nest. | |

Piciformes (woodpeckers)

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/Red-headed Woodpecker

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/Red-bellied Woodpecker

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/Pileated Woodpecker

Hummingbirds

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/Ruby-throated Hummingbird

Caprimulgiformes

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/Whip-poor-will

Galliformes (turkeys, chickens, grouse, quails, and pheasants)

| Colinus virginianus (Bobwhite Quail) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The Bobwhite Quail, Northern Bobwhite, or Virginia Quail, Colinus virginianus, is a ground-dwelling bird native to North America. The name derives from their characteristic call.

The Bobwhite Quail is a member of the group of species known as New World quail. These quail primarily inhabit areas of early successional growth dominated by various species of pine, hardwood, woody, and herbaceous growth. However, quail habitat varies greatly throughout their range which extends from Mexico east to Florida and north into the Upper Midwest and Northeast. Bobwhites are distinguished by a black cap and black stripe behind the eye along the head. The area in between is white on males and yellow-brown on females. The body is brown, speckled in places with black or white on both sexes, and average weight is five to six ounces (145-200 grams). It forms what are known as "coveys", groups of five to 30 birds, during the non-breeding season (roughly October-April). During the breeding season, typically beginning in mid-April, the Bobwhite coveys dissolve. Social pairs are typically formed between individuals of unknown relationship. These social pairings potentially result in the formation of a mate bond and subsequent female fertilization and egg formation. Eggs are laid at a rate of approximately 1 per day, and they hatch after 23 days. Eggs are normally white with a more pointed end than normal chicken eggs. Both males and females can incubate nests, with most nests predominantly incubated by females. If the first clutch of eggs is unsuccessful, a breeding pair (may be the same pair or a different pair as that which led to the previous nesting attempt) will attempt to lay, incubate, and hatch additional clutches. If the clutch is successful, chicks are precocial and will leave the nest approximately 24 hours following hatching. The breeding season continues until mid-October, and successful nesters (females) can potentially lay, incubate, and hatch up to 3 clutches. The Bobwhite's song is a rising, clear whistle, bob-Wight! or bob-bob-White! The call is most often given by males in spring and summertime. | |

| Bonasa umbellus (Ruffed Grouse) | |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| The Ruffed Grouse, Bonasa umbellus, is a medium-sized grouse occurring in forests across Canada and the Appalachian and northern United States including Alaska. They are non-migratory.

Ruffed Grouse have two distinct color phases, grey and red. In the grey phase, adults have a long square brownish tail with barring and a black subterminal band near the end. The head, neck and back are grey-brown; they have a light breast with barring. The ruffs are located on the sides of the neck. These birds also have a "crest" on top of their head, which sometimes lays flat. Both sexes are similarly marked and sized, making them difficult to tell apart, even in hand. The female often has a broken subterminal tail band, while males often have unbroken tail bands. Another fairly accurate method for sexing ruffed grouse involves inspection of the rump feathers. Feathers with a single white dot indicate a female, feathers with more than one white dot indicate that the bird is a male. Ruffed Grouse have never been successfully bred in captivity. These birds forage on the ground or in trees. They are omnivores, eating buds, leaves, berries, seeds, and insects. The male is often heard drumming on a fallen log in spring to attract females for mating. Females nest on the ground, typically laying 6-8 eggs. Grouse spend most of their time on the ground, and when surprised, may explode into flight, beating their wings very loudly. | |

Columbidae (doves and pigeons)

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/Rock Pigeon

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/Stock Pigeon

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/Turtle Dove

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/White-tipped Dove

Falconiformes (eagles, falcons, and hawks)

The Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), also known as the American Eagle, is a bird of prey found in North America, most recognizable as the national bird of the United States.

The species was on the brink of extinction in the US late in the 20th century, but now has a stable population and is in the process of being removed from the U.S. federal government's list of endangered species.

This eagle gets both its common and scientific names from the distinctive appearance of the adult's head. Bald in the English name refers to the white head feathers, and the scientific name is derived from Haliaeetus, New Latin for "sea eagle," (from the Ancient Greek haliaetos), and leucocephalus, Latinized Ancient Greek for "white head", from leukos ("white") and kephale ("head").

Description and systematics

An immature Bald Eagle has speckled brown plumage, the distinctive white head and body developing 2-3 years later, before sexual maturity. This species is distinguishable from the Golden Eagle in that the latter has feathers which extend down the legs. Also, the immature Bald Eagle has more light feathers in the upper arm area, especially around the 'armpit'.

Adult females have an average wingspan of about 7 feet (2.1 meters); adult males have a wingspan of 6 ft 6 in (2 meters). Adult females weigh approximately 12.8 lb (5.8 kg), males weigh 9 lb (4.1 kg). The smallest specimens are those from Florida, where an adult male may barely exceed 5 lb (2.3 kg) and a wingspan of 6 feet (1.8 meters). The largest are the Alaskan birds, where large females may exceed 15.5 lb (7 kg) and have a wingspan of approximately 8 feet (2.4 meters).

The northern birds are the subspecies washingtoniensis, whereas the southern ones belong to the nominate subspecies leucocephalus. They are separated approximately at latitude 38° N, or roughly the latitude of San Francisco; northern birds reach a bit further south on the Atlantic Coast, where they occur south to the Cape Hatteras area. Audubon's type specimen of "Washington's Eagle" - named in honor of George Washington& - was apparently an exceptionally large bird, such as are more often found in Alaska; these have been proposed as subspecies alascanus or alascensis, but the variation is clinal and follows Bergmann's Rule.

The Bald Eagle forms a species pair with the Eurasian White-tailed Eagle. These diverged from other Sea Eagles at the beginning of the Early Miocene (c. 10 mya) at latest, possibly - if the most ancient fossil record is correctly assigned to this genus - as early as the Early/Middle Oligocene, some 28 mya (Wink et al. 1996&). As in other sea-eagle species pairs, this one consists of a white-headed (the Bald Eagle) and a tan-headed species. They probably diverged in the North Pacific, spreading westwards into Eurasia and eastwards into North America. Like the third northern species, Steller's Sea-eagle, they have yellow talons, beaks and eyes in adults.

Bald Eagles are powerful fliers, and also soar on thermal convection currents.

In the wild, Bald Eagles can live about 20-30 years, and have a maximum life span of approximately 50 years. They generally live longer in captivity; up to 60 years old.

Bald Eagles normally squeak and have a shrill cry, punctuated by grunts. They do not make the "eagle scream" as often shown on the television. What many recognize as the call of this species is actually the call of a Red-tailed Hawk dubbed into the film.

Range, habitat, and restoration

The Bald Eagle's natural range covers most of North America, including most of Canada, all of the continental United States, and northern Mexico. The bird itself is able to live in most of North America's varied habitats from the bayous of Louisiana to the Sonoran desert and the eastern deciduous forests of Quebec and New England. It can be a migratory bird but it also is not unheard of for a nesting pair to overwinter in its breeding area.

Once a common sight in much of the continent, the Bald Eagle was severely affected by the use of the pesticide DDT in the mid-twentieth century. While the pesticide itself was not lethal to the bird, it made an eagle either sterile or unable to lay healthy eggs: the eagle would ingest the chemical through its food and then lay eggs that were too brittle to withstand the weight of a brooding adult. By the 1960s there were fewer than 500 nesting pairs in the 48 contiguous states of the USA.

Currently it is still slowly but steadily recovering its numbers; Organizations like the Fraternal Order of Eagles which carry the Eagle as their emblem, have helped the American Bald Eagle on its recovery, by supporting other groups that rescue and preserve the Eagles and their habitat. The Bald Eagle can be found in growing concentrations throughout the United States and Canada, particularly near large bodies of water. The U.S. state with the largest resident population is Alaska; out of the estimated 70,000 Bald Eagles on Earth, half live there.

Permits are required to keep this species in captivity (e-CFR 1974). As a rule, the Bald Eagle is a poor choice for public shows, being timid, prone to becoming highly stressed, and unpredictable in nature. As remarked above, they can be long-lived in captivity in key demands are met, but do not breed well even under the best conditions. The only Bald Eagle to be born outside North America hatched on May 3, 2006 in Magdeburg Zoo, Germany.

This species has occurred as a vagrant once in Ireland. The exhausted specimen was discovered by a national parks worker in a northern heath. Presumably, a storm blew it out to sea, and the bird struggled across the Atlantic Ocean.

Reproduction

Bald Eagles build huge nests out of branches, usually in large trees near water. The nest may stretch as large as eight feet across and weigh up to a ton (907kg). When breeding where there are no trees, the Bald Eagle will nest on the ground.

Eagles that are old enough to breed often return to the area where they were born. An adult looking for a site is likely to select a spot that contains other breeding Bald Eagles.

Bald Eagles are sexually mature at 4 or 5 years old. Eagles produce between one and three eggs per year, but it is rare for all three chicks to successfully fly. Both the male and female take turns sitting on the eggs. The other parent will hunt for food or look for nest material.

Diet

The Bald Eagle's diet is varied, including carrion, fish, smaller birds, rodents, and sometimes food scavenged or stolen from campsites and picnics. Most prey is quite a bit smaller than the eagle, but rare predatory attacks on large birds such as the Snow Goose, the Great Blue Heron or even swans have been recorded. Also, fairly large salmon and trout have been taken as well.

To hunt fish, easily their most important live prey, the eagle swoops down over the water and snatches the fish out of the water with its talons. They eat by holding the fish in one claw and tearing the flesh with the other. Eagles have structures on their toes called spiricules that allow them to grasp fish. Osprey also have this adaptation. Bald Eagles have powerful talons. In one case, an eagle was able to fly off with the 6.8 kg (15 lb) carcass of a Mule Deer fawn.

Sometimes, if the fish is too heavy to lift, the eagle will be dragged into the water. It may swim to safety, but some eagles drown or succumb to hypothermia. Occasionally, Bald Eagles will pirate fish away from Ospreys and usually the smaller raptors will have to give up their prey, a practice known as kleptoparasitism.

National bird of the U.S.

The Bald Eagle is the national bird of the United States of America. It is probably one of the country's most recognizable symbols, and appears on most of its official seals, including the Seal of the President of the United States.

Its national significance dates back to June 20, 1782, when the Continental Congress officially adopted the current design for the Great Seal of the United States including a Bald Eagle grasping arrows and an olive branch with its talons. Some states had earlier did so in 1778.

In 1784, after the end of the Revolutionary War, Benjamin Franklin wrote a famous letter to his daughter from Paris criticizing the choice and suggesting the Wild Turkey's character as a desirable trait:

For my own part I wish the Bald Eagle had not been chosen the Representative of our Country. He is a Bird of bad moral character. He does not get his Living honestly. You may have seen him perched on some dead Tree near the River, where, too lazy to fish for himself, he watches the Labour of the Fishing Hawk; and when that diligent Bird has at length taken a Fish, and is bearing it to his Nest for the Support of his Mate and young Ones, the Bald Eagle pursues him and takes it from him.

With all this Injustice, he is never in good Case but like those among Men who live by Sharping & Robbing he is generally poor and often very lousy. Besides he is a rank Coward: The little King Bird not bigger than a Sparrow attacks him boldly and drives him out of the District. He is therefore by no means a proper Emblem for the brave and honest country of America who have driven all the King birds from our Country...

I am on this account not displeased that the Figure is not known as a Bald Eagle, but looks more like a Turkey. For the Truth the Turkey is in Comparison a much more respectable Bird, and withal a true original Native of America . . . He is besides, though a little vain & silly, a Bird of Courage, and would not hesitate to attack a Grenadier of the British Guards who should presume to invade his Farm Yard with a red Coat on.

Despite Franklin's objections, the Bald Eagle remained the emblem of the United States. It can be found on both national seals and on the back of several coins (including the quarter dollar coin until 1999), with its head oriented towards the olive branch. Between 1916 and 1945, the Presidential Flag showed an eagle facing to its left (the viewer's right), which gave rise to the urban legend that the seal is changed to have the eagle face towards the olive branch in peace, and towards the arrows in wartime.&

Bald Eagles as religious objects

The Bald Eagle is a sacred bird in some North American cultures and its feathers, like those of the Golden Eagle, are central to many religious and spiritual customs amongst Native Americans. Some Native Americans revere eagles as sacred religious objects, including the feathers and other parts and are often compared to the Bible and crucifix (AP 2004).

Eagle feathers are often used in traditional ceremonies and are used to honor noteworthy achievements and qualities such as exceptional leadership and bravery.

Despite modern and historic Native American practices of giving eagle feathers to non-Native Americans and Native American members of other tribes who have been deemed worthy, current eagle feather law stipulates that only individuals of certifiable Native American ancestry enrolled in a federally recognized tribe are legally authorized to obtain Bald or Golden Eagle feathers for religious or spiritual use (AP 2002) Attempts to extend this permitted use have met with resistance from members of federally recognized Native American tribes, who even under the permissive legislation sometimes have to wait for years before a good specimen can be procured for their use (AP 2004).

References

- Associated Press (AP) (2002): Native American gets OK to use eagle feathers in religious practices. Retrieved 2006-NOV-30.

- Associated Press (AP) (2004): Residents fight to use eagle feathers. Retrieved 2006-NOV-30.

- Template:IUCN2006 Database entry includes justification for why this species is of least concern

- Boradiansky, Tina S. (1990): Conflicting Values: The Religious Killing of Federally Protected Wildlife. Retrieved 2006-NOV-30.

- DeMeo, Antonia M. (1995): Access to Eagles and Eagle Parts: Environmental Protection v. Native American Free Exercise of Religion. Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly 22(3): 771-813. HTML fulltext

- Electronic Code of Federal Regulations (e-CFR) (1974): Title 50: Wildlife and Fisheries. Part 22 - Eagle Permits. HTML fulltext

- Wink, M.; Heidrich, P. & Fentzloff, C. (1996): A mtDNA phylogeny of sea eagles (genus Haliaeetus) based on nucleotide sequences of the cytochrome b gene. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 24: 783-791. Template:DOI PDF fulltext

Footnotes

- ↑ As explicitly stated by Audubon. However, the subspecific name he chose - washingtoniensis - means properly "from Washington (state)". There has been considerable confusion, with some authors changing it to washingtoni, "(George) Washington's", but the form as originally written is correct.

- ↑ The authors' reservations about using the generalized "2%" rate of molecular evolution have since proven to be well-founded.

- ↑ "http://www.snopes.com/history/american/turnhead.htm". http://www.snopes.com/history/american/turnhead.htm.

External links

- Bald Eagle Info.com. Retrieved 2006-NOV-30.

- BirdHouses101.com: Bald Eagle. Retrieved 2006-NOV-30.

- Cascades Raptor Center. Retrieved 2006-NOV-30.

- GreatSeal.com: The Eagle, Ben Franklin, and the Turkey. Retrieved 2006-NOV-30.

- NE Energy: Barton Island, Massachusetts, Bald Eagle webcam. Retrieved 2006-NOV-30.

- USFWS: 1.24 MB Bald Eagle JPEG. Retrieved 2006-NOV-30.

be:Белагаловы арол cs:Orel bělohlavý da:Hvidhovedet havørn de:Weißkopfseeadler es:Pigargo cabeciblanco eo:Blankkapa maraglo fr:Pygargue à tête blanche it:Haliaeetus leucocephalus he:עיטם לבן ראש nl:Amerikaanse zeearend cr:ᒥᒋᓲ ja:ハクトウワシ pl:Bielik amerykański pt:Águia de cabeça branca sk:Orliak bielohlavý fi:Valkopäämerikotka sv:Vithövdad havsörn ta:வெண்தலைக் கழுகு

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/Golden Eagle

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/Falco peregrinus

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/Red-tail Hawk

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/Osprey

Ciconiiformes (storks, herons, egrets)

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/Great Blue Heron

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/Great Egret

Charadriiformes (waders, gulls, and auks)

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/Herring Gull

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/Semipalmated Sandpiper

Anseriformes (ducks, geese, and swans)

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/Canada Goose

Adventist Youth Honors Answer Book/Nature/Birds/Northern Pintail