Difference between revisions of "AY Honors/Marine Algae/Answer Key/es"

(Updating to match new version of source page) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{HonorSubpage}} | |

| − | |||

| − | {{ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | }} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<section begin="Body" /> | <section begin="Body" /> | ||

{{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=1}} | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=1}} | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <noinclude><div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| − | <!-- 1. What is marine algae? | + | </noinclude> |

| + | <!-- 1. What is marine algae? --> | ||

The most common name for marine algae is "''seaweed''". Seaweeds are popularly described as plants, but biologists do not consider them plants (in biology, all true plants belong to the kingdom Plantae). They should not be confused with aquatic plants such as seagrasses (which are vascular plants). | The most common name for marine algae is "''seaweed''". Seaweeds are popularly described as plants, but biologists do not consider them plants (in biology, all true plants belong to the kingdom Plantae). They should not be confused with aquatic plants such as seagrasses (which are vascular plants). | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| + | <noinclude> | ||

| + | </div></noinclude> | ||

{{CloseReq}} <!-- 1 --> | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 1 --> | ||

{{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=2}} | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=2}} | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <noinclude><div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| − | <!-- 2. Where is it found? | + | </noinclude> |

| + | <!-- 2. Where is it found? --> | ||

Marine algae are mostly found in shallow ocean water near rocky shores. It is also found in fresh water, such as ponds, lakes, and rivers. | Marine algae are mostly found in shallow ocean water near rocky shores. It is also found in fresh water, such as ponds, lakes, and rivers. | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| + | <noinclude> | ||

| + | </div></noinclude> | ||

{{CloseReq}} <!-- 2 --> | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 2 --> | ||

{{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=3}} | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=3}} | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <noinclude><div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| − | <!-- 3. What is the organ of attachment to the substratum called? How does it differ from a true root? | + | </noinclude> |

| + | <!-- 3. What is the organ of attachment to the substratum called? How does it differ from a true root? --> | ||

The organ that attaches a marine algae to a substrate is called a '''''"holdfast"'''''. Unlike a root, a holdfast derives no nutrients from this intimate contact with the substrate.<br> | The organ that attaches a marine algae to a substrate is called a '''''"holdfast"'''''. Unlike a root, a holdfast derives no nutrients from this intimate contact with the substrate.<br> | ||

Holdfasts vary in shape and form depending on both the species and the substrate type. The holdfasts of organisms that live in muddy substrates often have complex tangles of root-like growths, while those of organisms that live in sandy substrates are bulb-like and very flexible, such as the holdfast of sea pens, allowing the organism(s) to pull the entire body into the substrate when the holdfast is contracted. The holdfasts of organisms that live on smooth surfaces (such as the surface of a boulder) have the base of the holdfast literally glued to the surface. | Holdfasts vary in shape and form depending on both the species and the substrate type. The holdfasts of organisms that live in muddy substrates often have complex tangles of root-like growths, while those of organisms that live in sandy substrates are bulb-like and very flexible, such as the holdfast of sea pens, allowing the organism(s) to pull the entire body into the substrate when the holdfast is contracted. The holdfasts of organisms that live on smooth surfaces (such as the surface of a boulder) have the base of the holdfast literally glued to the surface. | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| + | <noinclude> | ||

| + | </div></noinclude> | ||

{{CloseReq}} <!-- 3 --> | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 3 --> | ||

{{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=4}} | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=4}} | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <noinclude><div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| − | <!-- 4. How does size vary in marine algae? | + | </noinclude> |

| + | <!-- 4. How does size vary in marine algae? --> | ||

Some marine algae are so small they can only be seen under a microscope. Others are very large, such as Macrocystis, a species of kelp belonging to the brown algae group, which may reach {{units|60 meters|200 ft}} in length. | Some marine algae are so small they can only be seen under a microscope. Others are very large, such as Macrocystis, a species of kelp belonging to the brown algae group, which may reach {{units|60 meters|200 ft}} in length. | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| + | <noinclude> | ||

| + | </div></noinclude> | ||

{{CloseReq}} <!-- 4 --> | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 4 --> | ||

{{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=5}} | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=5}} | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <noinclude><div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| − | <!-- 5. Name the four groups of marine algae, indicating opposite the name of each group whether it is unicellular, multicellular, or both. | + | </noinclude> |

| + | <!-- 5. Name the four groups of marine algae, indicating opposite the name of each group whether it is unicellular, multicellular, or both. --> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

{| border=1 cellspacing="1" cellpadding="4" align="center" style="background:#c0ffff" | {| border=1 cellspacing="1" cellpadding="4" align="center" style="background:#c0ffff" | ||

| Line 59: | Line 65: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| + | <noinclude> | ||

| + | </div></noinclude> | ||

{{CloseReq}} <!-- 5 --> | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 5 --> | ||

{{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=6}} | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=6}} | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <noinclude><div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| − | <!-- 6. Is most green algae found in fresh or salt water? | + | </noinclude> |

| + | <!-- 6. Is most green algae found in fresh or salt water? --> | ||

While about 90% of the species of green algae live in freshwater habitats and most of the other 10% live in marine habitats, other species are adapted to a wide range of environments. Watermelon snow, or ''Chlamydomonas nivalis'', of the class Chlorophyceae, lives on summer alpine snowfields. Others live attached to rocks or woody parts of trees. Some lichens are symbiotic relationships with fungi and a green alga. | While about 90% of the species of green algae live in freshwater habitats and most of the other 10% live in marine habitats, other species are adapted to a wide range of environments. Watermelon snow, or ''Chlamydomonas nivalis'', of the class Chlorophyceae, lives on summer alpine snowfields. Others live attached to rocks or woody parts of trees. Some lichens are symbiotic relationships with fungi and a green alga. | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| + | <noinclude> | ||

| + | </div></noinclude> | ||

{{CloseReq}} <!-- 6 --> | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 6 --> | ||

{{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=7}} | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=7}} | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <noinclude><div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| − | <!-- 7. What are diatoms? | + | </noinclude> |

| + | <!-- 7. What are diatoms? --> | ||

Diatoms are a major group of algae, and are one of the most common types of phytoplankton. Most diatoms are unicellular, although some form chains or simple colonies. A characteristic feature of diatom cells is that they are encased within a unique cell wall made of silica (hydrated silicon dioxide) called a frustule. These frustules show a wide diversity in form, some quite beautiful and ornate, but usually consist of two asymmetrical sides with a split between them, hence the group name. | Diatoms are a major group of algae, and are one of the most common types of phytoplankton. Most diatoms are unicellular, although some form chains or simple colonies. A characteristic feature of diatom cells is that they are encased within a unique cell wall made of silica (hydrated silicon dioxide) called a frustule. These frustules show a wide diversity in form, some quite beautiful and ornate, but usually consist of two asymmetrical sides with a split between them, hence the group name. | ||

| + | </div> | ||

Las diatomeas son un grupo amplio y se pueden encontrar en los océanos, en agua dulce, en la tierra y en las superficies húmedas. La mayoría viven en aguas abiertas, aunque algunos viven en las capas superficiales de la interfase agua-sedimento, o incluso en condiciones atmosféricas húmedas. Son especialmente importantes en los océanos, donde se estima que contribuyen hasta un 45% de la base de la cadena alimentaria oceánica. | Las diatomeas son un grupo amplio y se pueden encontrar en los océanos, en agua dulce, en la tierra y en las superficies húmedas. La mayoría viven en aguas abiertas, aunque algunos viven en las capas superficiales de la interfase agua-sedimento, o incluso en condiciones atmosféricas húmedas. Son especialmente importantes en los océanos, donde se estima que contribuyen hasta un 45% de la base de la cadena alimentaria oceánica. | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| + | <noinclude> | ||

| + | </div></noinclude> | ||

{{CloseReq}} <!-- 7 --> | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 7 --> | ||

{{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=8}} | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=8}} | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <noinclude><div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| − | <!-- 8. Where does algae grow-the polar, temperate, or tropic zone? | + | </noinclude> |

| + | <!-- 8. Where does algae grow-the polar, temperate, or tropic zone? --> | ||

Algae grow in ''all'' of these zones, from Picobiliphytes, which are an algae indigenous to polar regions, to Sargassum, which lives in the tropical waters of the Atlantic Ocean. | Algae grow in ''all'' of these zones, from Picobiliphytes, which are an algae indigenous to polar regions, to Sargassum, which lives in the tropical waters of the Atlantic Ocean. | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| + | <noinclude> | ||

| + | </div></noinclude> | ||

{{CloseReq}} <!-- 8 --> | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 8 --> | ||

{{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=9}} | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=9}} | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <noinclude><div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| − | <!-- 9. Where is brown algae most invariably found-in fresh or salt water? | + | </noinclude> |

| + | <!-- 9. Where is brown algae most invariably found-in fresh or salt water? --> | ||

Brown algae is found in most salt water ecosystems. | Brown algae is found in most salt water ecosystems. | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| + | <noinclude> | ||

| + | </div></noinclude> | ||

{{CloseReq}} <!-- 9 --> | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 9 --> | ||

{{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=10}} | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=10}} | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <noinclude><div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| − | <!-- 10. What is the greatest depth that algae grows in the ocean? Why can it not grow in deeper water? | + | </noinclude> |

| + | <!-- 10. What is the greatest depth that algae grows in the ocean? Why can it not grow in deeper water? --> | ||

The deepest living algae are those that are attached to the sea-bed under several meters of water. The limiting factor in such cases is the availability of sufficient sunlight to support photosynthesis. The deepest living seaweeds are the various kelps. | The deepest living algae are those that are attached to the sea-bed under several meters of water. The limiting factor in such cases is the availability of sufficient sunlight to support photosynthesis. The deepest living seaweeds are the various kelps. | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| + | <noinclude> | ||

| + | </div></noinclude> | ||

{{CloseReq}} <!-- 10 --> | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 10 --> | ||

{{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=11}} | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=11}} | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <noinclude><div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| − | <!-- 11. Name the three parts of a large kelp. How do they compare to the leaf, stem, and root of a plant? | + | </noinclude> |

| + | <!-- 11. Name the three parts of a large kelp. How do they compare to the leaf, stem, and root of a plant? --> | ||

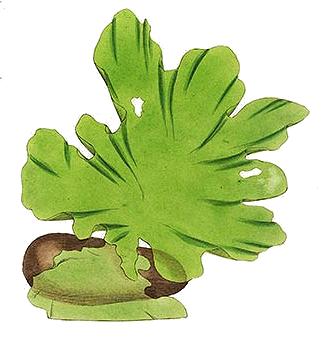

[[Image:Seaweed holdfast.jpg|thumb|300px|A marine algae showing the holdfast, some stipes, and some blades]] | [[Image:Seaweed holdfast.jpg|thumb|300px|A marine algae showing the holdfast, some stipes, and some blades]] | ||

;Blade: The ''blade'' is a large, flat structure, and is analogous to a plant's leaves. | ;Blade: The ''blade'' is a large, flat structure, and is analogous to a plant's leaves. | ||

;Stipe: The ''stipe'' serves as a stem to which the blades are attached. | ;Stipe: The ''stipe'' serves as a stem to which the blades are attached. | ||

| − | ;Holdfast: The ''holdfast'' is the part of the plant that anchors it to a substrate, such as a rock or the seafloor. | + | ;Holdfast: The ''holdfast'' is the part of the plant that anchors it to a substrate, such as a rock or the seafloor. It is analogous to a plant's root. |

<br style="clear:both"> | <br style="clear:both"> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| + | <noinclude> | ||

| + | </div></noinclude> | ||

{{CloseReq}} <!-- 11 --> | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 11 --> | ||

{{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=12}} | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=12}} | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <noinclude><div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| − | <!-- 12. Describe the two ways that algae reproduce. | + | </noinclude> |

| + | <!-- 12. Describe the two ways that algae reproduce. --> | ||

===Sexual Reproduction=== | ===Sexual Reproduction=== | ||

| − | Most forms of algae reproduce sexually by forming spores. The spores, when cast off the adult organism, develop into male and female gametes which carry only half the genetic information of the parent organism. These gametes are motile, meaning they can move around by themselves, propelled by tiny flagella. When male and female gametes from the same or from different parent organisms combine, the genetic material fuses to create an organism with a full complement of genetic material. This is very similar to the way that ferns reproduce (see the [[ | + | Most forms of algae reproduce sexually by forming spores. The spores, when cast off the adult organism, develop into male and female gametes which carry only half the genetic information of the parent organism. These gametes are motile, meaning they can move around by themselves, propelled by tiny flagella. When male and female gametes from the same or from different parent organisms combine, the genetic material fuses to create an organism with a full complement of genetic material. This is very similar to the way that ferns reproduce (see the [[AY Honors/Ferns|Ferns]] honor for more details. |

===Asexual Reproduction=== | ===Asexual Reproduction=== | ||

Asexual reproduction is advantageous in that it permits efficient population increases, but less variation is possible. Sexual reproduction allows more variation but is more costly because of the waste of gametes that fail to mate, among other things. Often there is no strict alternation between the sporophyte and gametophyte phases and also because there is often an asexual phase, which could include the fragmentation of the thallus. | Asexual reproduction is advantageous in that it permits efficient population increases, but less variation is possible. Sexual reproduction allows more variation but is more costly because of the waste of gametes that fail to mate, among other things. Often there is no strict alternation between the sporophyte and gametophyte phases and also because there is often an asexual phase, which could include the fragmentation of the thallus. | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| + | <noinclude> | ||

| + | </div></noinclude> | ||

{{CloseReq}} <!-- 12 --> | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 12 --> | ||

{{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=13}} | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=13}} | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <noinclude><div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| − | <!-- 13. What are some of the commercial values of algae? Give at least one for each group. | + | </noinclude> |

| + | <!-- 13. What are some of the commercial values of algae? Give at least one for each group. --> | ||

;Food: Most cultures with access to Porphyra, a genus of red algae use it as a food or somehow in the diet, making it perhaps the most domesticated of the marine algae. It is known as laver, nori sushi (Japanese), amanori (Japanese), zakai, gim sushi (Korean), zicai (Chinese), karengo, sloke or slukos. In Japan, the annual production of Porphyra spp. is valued at 100 billion yen (US$1 billion).<br> | ;Food: Most cultures with access to Porphyra, a genus of red algae use it as a food or somehow in the diet, making it perhaps the most domesticated of the marine algae. It is known as laver, nori sushi (Japanese), amanori (Japanese), zakai, gim sushi (Korean), zicai (Chinese), karengo, sloke or slukos. In Japan, the annual production of Porphyra spp. is valued at 100 billion yen (US$1 billion).<br> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

<div class="mw-translate-fuzzy"> | <div class="mw-translate-fuzzy"> | ||

| Line 132: | Line 170: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| + | <noinclude> | ||

| + | </div></noinclude> | ||

{{CloseReq}} <!-- 13 --> | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 13 --> | ||

{{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=14}} | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=14}} | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <noinclude><div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| − | <!-- 14. Make a collection of at least twenty specimen of marine algae properly identified, mounted, and labeled. There must be at least four specimens from the Green group, eight from the Brown group, and eight from the Red group. | + | </noinclude> |

| − | The best approach for meeting this requirement is to obtain a field guide to algae, go out to a beach, and collect the various types you find. Once you have a specimen, use the field guide to try to identify it. | + | <!-- 14. Make a collection of at least twenty specimen of marine algae properly identified, mounted, and labeled. There must be at least four specimens from the Green group, eight from the Brown group, and eight from the Red group. --> |

| + | The best approach for meeting this requirement is to obtain a field guide to algae, go out to a beach, and collect the various types you find. Once you have a specimen, use the field guide to try to identify it. Continue collecting until you have at least 20 specimens you can identify, being absolutely sure to remove any animals living in the algae before you leave the area. You can collect the specimens in a bucket or keep them in plastic bags.<br> | ||

You will need to start the drying process right away. For this you will need: | You will need to start the drying process right away. For this you will need: | ||

* A shallow tray (such as from a cafeteria, or a cookie sheet) | * A shallow tray (such as from a cafeteria, or a cookie sheet) | ||

| Line 158: | Line 199: | ||

# Repeat for each sample, stacking them on atop the other, separated by blotters. | # Repeat for each sample, stacking them on atop the other, separated by blotters. | ||

# When the last specimen has been covered, lay the second piece of plywood over assembly. | # When the last specimen has been covered, lay the second piece of plywood over assembly. | ||

| − | # Bind the "sandwich" with the nylon straps or belts, and tighten as best you can. | + | # Bind the "sandwich" with the nylon straps or belts, and tighten as best you can. Alternately, you could use C-clamps to clamp the sandwich together, or you could place heavy weights on the entire assembly. |

# Place in a well-ventilated area | # Place in a well-ventilated area | ||

# Change the newspaper and blotter paper daily for the next five days or until the samples are dry.<br> | # Change the newspaper and blotter paper daily for the next five days or until the samples are dry.<br> | ||

Many types of algae have natural adhesives in them that will cause them to stick to the mounting paper all by themselves. For those that do not, a ''small'' dot of white glue may be used to affix them to the mounting paper. Label with the information collected about the specimen. | Many types of algae have natural adhesives in them that will cause them to stick to the mounting paper all by themselves. For those that do not, a ''small'' dot of white glue may be used to affix them to the mounting paper. Label with the information collected about the specimen. | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| + | <noinclude> | ||

| + | </div></noinclude> | ||

{{CloseReq}} <!-- 14 --> | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 14 --> | ||

{{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=15}} | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=15}} | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <noinclude><div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| + | </noinclude> | ||

<!-- 15. Be able to identify by generic name at least ten types of marine algae. --> | <!-- 15. Be able to identify by generic name at least ten types of marine algae. --> | ||

The "generic" name in the requirement means that you should learn which genus ten specimens belong to. Don't be scared of the scientific names (Latin names) - they are no more difficult to learn than the common names, especially if you know neither when you start.<br> | The "generic" name in the requirement means that you should learn which genus ten specimens belong to. Don't be scared of the scientific names (Latin names) - they are no more difficult to learn than the common names, especially if you know neither when you start.<br> | ||

| Line 178: | Line 223: | ||

| image_caption = Ulva lactuca From Sowerby's English botany, 1790-1814. By James Sowerby (1757-1822). | | image_caption = Ulva lactuca From Sowerby's English botany, 1790-1814. By James Sowerby (1757-1822). | ||

| range = | | range = | ||

| − | | description = ''Ulva lactuca'' is a thin flat green alga growing from a discoid holdfast. The margin is somewhat ruffled and often torn. It may reach 18 cm or more long though generally much less and up to 30 cm across. | + | | description = ''Ulva lactuca'' is a thin flat green alga growing from a discoid holdfast. The margin is somewhat ruffled and often torn. It may reach 18 cm or more long though generally much less and up to 30 cm across. The membrane is two cells thick, soft and translucent and grows attached, without a stipe, to rock via a small disc-shaped holdfast. Green to dark green in color this species in the Chlorophyta is formed of two layers of cells irregularly arranged, as seen in cross section. The chloroplast is cup-shaped with 1 to 3 pyrenoids. |

}} | }} | ||

| + | </div> | ||

{{Species id | {{Species id | ||

| Line 416: | Line 462: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | <noinclude></noinclude> | + | <div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> |

| + | <noinclude> | ||

| + | </div></noinclude> | ||

{{CloseReq}} <!-- 15 --> | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 15 --> | ||

<noinclude><div class="mw-translate-fuzzy"> | <noinclude><div class="mw-translate-fuzzy"> | ||

| Line 425: | Line 473: | ||

<noinclude> | <noinclude> | ||

</div></noinclude> | </div></noinclude> | ||

| − | + | {{CloseHonorPage}} | |

Revision as of 13:39, 16 April 2021

Nivel de destreza

3

Año

1961

Version

10.02.2026

Autoridad de aprobación

Asociación General

1

The most common name for marine algae is "seaweed". Seaweeds are popularly described as plants, but biologists do not consider them plants (in biology, all true plants belong to the kingdom Plantae). They should not be confused with aquatic plants such as seagrasses (which are vascular plants).

2

Marine algae are mostly found in shallow ocean water near rocky shores. It is also found in fresh water, such as ponds, lakes, and rivers.

3

The organ that attaches a marine algae to a substrate is called a "holdfast". Unlike a root, a holdfast derives no nutrients from this intimate contact with the substrate.

Holdfasts vary in shape and form depending on both the species and the substrate type. The holdfasts of organisms that live in muddy substrates often have complex tangles of root-like growths, while those of organisms that live in sandy substrates are bulb-like and very flexible, such as the holdfast of sea pens, allowing the organism(s) to pull the entire body into the substrate when the holdfast is contracted. The holdfasts of organisms that live on smooth surfaces (such as the surface of a boulder) have the base of the holdfast literally glued to the surface.

4

Some marine algae are so small they can only be seen under a microscope. Others are very large, such as Macrocystis, a species of kelp belonging to the brown algae group, which may reach 60 meters![]() in length.

in length.

5

6

While about 90% of the species of green algae live in freshwater habitats and most of the other 10% live in marine habitats, other species are adapted to a wide range of environments. Watermelon snow, or Chlamydomonas nivalis, of the class Chlorophyceae, lives on summer alpine snowfields. Others live attached to rocks or woody parts of trees. Some lichens are symbiotic relationships with fungi and a green alga.

7

Diatoms are a major group of algae, and are one of the most common types of phytoplankton. Most diatoms are unicellular, although some form chains or simple colonies. A characteristic feature of diatom cells is that they are encased within a unique cell wall made of silica (hydrated silicon dioxide) called a frustule. These frustules show a wide diversity in form, some quite beautiful and ornate, but usually consist of two asymmetrical sides with a split between them, hence the group name.

Las diatomeas son un grupo amplio y se pueden encontrar en los océanos, en agua dulce, en la tierra y en las superficies húmedas. La mayoría viven en aguas abiertas, aunque algunos viven en las capas superficiales de la interfase agua-sedimento, o incluso en condiciones atmosféricas húmedas. Son especialmente importantes en los océanos, donde se estima que contribuyen hasta un 45% de la base de la cadena alimentaria oceánica.

8

Algae grow in all of these zones, from Picobiliphytes, which are an algae indigenous to polar regions, to Sargassum, which lives in the tropical waters of the Atlantic Ocean.

9

Brown algae is found in most salt water ecosystems.

10

The deepest living algae are those that are attached to the sea-bed under several meters of water. The limiting factor in such cases is the availability of sufficient sunlight to support photosynthesis. The deepest living seaweeds are the various kelps.

11

- Blade

- The blade is a large, flat structure, and is analogous to a plant's leaves.

- Stipe

- The stipe serves as a stem to which the blades are attached.

- Holdfast

- The holdfast is the part of the plant that anchors it to a substrate, such as a rock or the seafloor. It is analogous to a plant's root.

12

Sexual Reproduction

Most forms of algae reproduce sexually by forming spores. The spores, when cast off the adult organism, develop into male and female gametes which carry only half the genetic information of the parent organism. These gametes are motile, meaning they can move around by themselves, propelled by tiny flagella. When male and female gametes from the same or from different parent organisms combine, the genetic material fuses to create an organism with a full complement of genetic material. This is very similar to the way that ferns reproduce (see the Ferns honor for more details.

Asexual Reproduction

Asexual reproduction is advantageous in that it permits efficient population increases, but less variation is possible. Sexual reproduction allows more variation but is more costly because of the waste of gametes that fail to mate, among other things. Often there is no strict alternation between the sporophyte and gametophyte phases and also because there is often an asexual phase, which could include the fragmentation of the thallus.

13

- Food

- Most cultures with access to Porphyra, a genus of red algae use it as a food or somehow in the diet, making it perhaps the most domesticated of the marine algae. It is known as laver, nori sushi (Japanese), amanori (Japanese), zakai, gim sushi (Korean), zicai (Chinese), karengo, sloke or slukos. In Japan, the annual production of Porphyra spp. is valued at 100 billion yen (US$1 billion).

- Emulsionante

- Extractos de algas marinas gelatinosas de carragenina (también conocido como musgo de Irlanda, un alga roja) se han utilizado como aditivos alimentarios por cientos de años. Actúa como un emulsionante, es decir, ayuda a combinar elementos que resisten la combinación, tales como aceite y agua. Es comúnmente usado en la pasta dental, helados, batidos, salsas e incluso champú (que admitimos no es un alimento).

- Fertilizante

- Algas marinas, particularmente el fucus, kelp o laminaria (que son todas las formas de algas pardas), se puede aplicar al suelo como abono (aunque tenderá a descomponerse muy rápidamente) o puede ser añadido a la pila de compost, donde es un excelente activador.

- Medicina

- Laminaria (un género de algas pardas) se utiliza en la producción de cloruro de potasio y yodo. Palos de laminaria secas se pueden utilizar medicinalmente para inducir la dilatación del cuello del útero. Un uso medicinal adicional de algas es el producto agar que se utiliza como un medio de cultivo para el crecimiento de bacterias en el laboratorio.

- Pigmentos

- Los pigmentos naturales producidos por las algas se pueden usar como una alternativa a los colorantes químicos y agentes colorantes. Muchos de los productos de papel utilizados en la actualidad no son reciclables debido a las tintas químicas que utilizan. Los recicladores de papel han encontrado que las tintas a base de algas son mucho más fáciles de romper. También hay mucho interés en la industria de alimentos en la sustitución de los agentes colorantes que se utilizan actualmente con colorantes derivados de pigmentos de algas. En Israel, una especie de alga verde se cultiva en tanques de agua y después expuestos a la luz solar directa y el calor hace que se vuelva de color rojo brillante. Después se cosecha y se utiliza como un pigmento natural para alimentos como el salmón.

14

The best approach for meeting this requirement is to obtain a field guide to algae, go out to a beach, and collect the various types you find. Once you have a specimen, use the field guide to try to identify it. Continue collecting until you have at least 20 specimens you can identify, being absolutely sure to remove any animals living in the algae before you leave the area. You can collect the specimens in a bucket or keep them in plastic bags.

You will need to start the drying process right away. For this you will need:

- A shallow tray (such as from a cafeteria, or a cookie sheet)

- Mounting paper (herbarium paper or drawing paper)

- Wax paper

- Mailing labels or strips of paper

- Newspaper or blotter paper

- Two small pieces of plywood

- Nylon straps or belts, or C clamps

Follow this procedure:

- Rinse the alga to remove salt, sand and foreign particles.

- place one of the small pieces of plywood on a work surface and cover it with a layer of blotter paper (or newspaper).

- Fill the shallow pan with water and float the mounting paper in it.

- Float the algae specimen on the mounting paper, spreading the fronds out as best you can.

- Carefully lift the mounting paper with the algae specimen out of the water, draining off the water as you lift it up.

- Lay the mounting paper on the blotter paper placed on the sheet of plywood earlier.

- Cover the sample (still on the mounting paper) with a sheet of wax paper

- Put your name and the specimen's identity on the mailing label, and place it on the wax paper.

- Cover this with another layer of blotter paper and/or newspaper.

- Repeat for each sample, stacking them on atop the other, separated by blotters.

- When the last specimen has been covered, lay the second piece of plywood over assembly.

- Bind the "sandwich" with the nylon straps or belts, and tighten as best you can. Alternately, you could use C-clamps to clamp the sandwich together, or you could place heavy weights on the entire assembly.

- Place in a well-ventilated area

- Change the newspaper and blotter paper daily for the next five days or until the samples are dry.

Many types of algae have natural adhesives in them that will cause them to stick to the mounting paper all by themselves. For those that do not, a small dot of white glue may be used to affix them to the mounting paper. Label with the information collected about the specimen.

15

The "generic" name in the requirement means that you should learn which genus ten specimens belong to. Don't be scared of the scientific names (Latin names) - they are no more difficult to learn than the common names, especially if you know neither when you start.

We present several species below, but you should not expect that these are the only samples you will find. Get a good field guide and identify the algae you find rather than trying to find the algae you can identify.

Green Algae

Sea Lettuce (Ulva lactuca)

Descripción: Ulva lactuca is a thin flat green alga growing from a discoid holdfast. The margin is somewhat ruffled and often torn. It may reach 18 cm or more long though generally much less and up to 30 cm across. The membrane is two cells thick, soft and translucent and grows attached, without a stipe, to rock via a small disc-shaped holdfast. Green to dark green in color this species in the Chlorophyta is formed of two layers of cells irregularly arranged, as seen in cross section. The chloroplast is cup-shaped with 1 to 3 pyrenoids.

Codium (Codium fragile)

Descripción: El género tiene talos de dos formas, erecto o postrado. Las plantas erectas son dicotómicamente ramificadas a 40 cm de largo con ramas que forman una estructura esponjosa compacto, no calcárea. Las ramas finales forman una capa superficial y estrecha de corteza empalizada de utrículos. Las especies que no son erguidas forman un postrado o un talo globular con una superficie aterciopelada, las ramas finales formando una estrecha corteza de utrículos.

Red de agua (Hydrodictyon reticulatum)

Descripción: A veces llamado red de agua, tiene una forma que parece como un saco hueco en forma de red. Puede crecer hasta varios decímetros.

Pediastrum (Pediastrum simplex)

Descripción: El nombre Pediastrum significa «estrella normal», porque esta alga tiene forma de estrella. Se puede encontrar en muchos estanques, haciendo que el agua aparezca verdosa.

Volvox (Volvox aureus)

Dónde se encuentra: Volvox se encuentra en estanques y zanjas, y hasta en charcos. El lugar mejor para buscar es en los estanques más profundos, lagunas y acequias que reciben una gran cantidad de lluvia. Se ha dicho que cuando se encuentra lemna, es probable encontrar Volvox; y es cierto que dicha agua es favorable, pero el sombreado es desfavorable.

Descripción: The cells swim in a coordinated fashion, with a distinct anterior and posterior - or since Volvox resembles a little planet, a 'north and south' pole. The cells have eyespots, more developed near the anterior, which enables the colony to swim towards light. Volvox es uno de los clorofitos más conocidos y es el más desarrollado en una serie de géneros que forman colonias esféricas. Cada volvox se compone de numerosas células flageladas similares a Chlamydomonas, de 1000-3000 en total, interconectadas y arregladas en una esfera llena de glicoproteína (coenobium). Las células nadan de manera coordinada, con una distinción de anterior y posterior - o, como volvox se parece a un pequeño planeta, un polo 'norte y sur'. Las células tienen manchas oculares y son más desarrolladas cerca de la parte anterior, que permite a la colonia a nadar hacia la luz.

Alga Parda

Sargazo (Sargassum muticum)

Descripción: El sargazo es un alga parda grande de la clase Phaeophyceae. Crece unido a las rocas por un rizoide perenne de hasta 5 cm de diámetro. A partir de este rizoide el eje principal crece hasta un máximo de 5 cm de altura. Las láminas parecidas a hojas y ramas laterales primarias crecen de esta estípite. En aguas cálidas puede crecer hasta 12 metros. Sin embargo, en aguas británicas crece a no más de 4 metros de largo. El rizoide da lugar a un único eje principal con ramas secundarias y terciarias que son vertidas anualmente. Numerosas pequeñas vesículas acechadas de aire de 2.6 mm proporcionan flotabilidad. Los receptáculos reproductivos también son acosadas y se desarrollan en las axilas de las láminas. Es auto fértil.

Sargazo gigante, huiro, cochayuyo, chascón (Macrocystis)

Descripción: Macrocystis es un género de algas, de los cuales algunas son tan enormes que las plantas pueden crecer hasta 60 metros. Los estípites surgen de un rizoide y se dividen tres o cuatro veces cerca de la base. Hojas desarrollan a intervalos irregulares a lo largo del estípite. M. pyrifera crece a más de 45 m de largo. Los estípites no se dividen y cada uno tiene una vejiga de gas en su base.

Cola de pavo (Padina pavonica)

Descripción: Padina pavonica, conocido comúnmente como Cola de pavo, es un alga parda que se encuentra en el Océano Atlántico. Actúa como un precursor de la elastina cuando se aplica tópicamente, empezando producción de colágeno en la piel, aumentando así la elasticidad de la piel.

Fucus (Fucus spiralis)

Descripción: Fucus spiralis es de color olivo y similar a Fucus vesiculosus y Fucus serrato. Crece hasta 30 cm de largo y se divide irregularmente. Se une por un rizoide. La hoja aplanada tiene una nervadura central clara y suele ser retorcida en espiral y sin un borde dentado, como visto en Fucus serrato, y que no muestra vesículas de aire, como e Fucus vesiculosus.

Sargazo vesiculoso, alga negra (Fucus vesiculosus)

Dónde se encuentra: Fucus vesiculosus es una de las algas más comunes en las costas de las Islas Británicas. Se registra desde las costas atlánticas de Europa, el Mar Báltico, Groenlandia, Azores, las Canarias y Madeira. También aparece en la costa atlántica de Norteamérica de la isla de Ellesmere, Hudson Bay a Carolina del Norte.

Descripción: Fucus vesiculosus es un alga muy variable. Puede crecer hasta 100 cm o más y es fácilmente reconocido por las pequeñas vesículas llenas de gas que se producen en pares a cada lado de un nervio central que corre a lo largo del centro de la fronda. Era la fuente original de yodo, descubierta en 1811, y fue usada extensivamente para tratar el bocio, una inflamación de la glándula tiroides relacionada con la deficiencia de yodo. Un alimento común en Japón, alga negra se utiliza como un aditivo y saborizante en varios productos alimenticios en Europa. El alga negra es comúnmente encontrada como un componente de las tabletas y polvos de kelp usados como suplementos nutricionales. A veces se le «kelp», pero ese término técnicamente se refiere a un alga marina diferente.

Alga dentada o serrada (Fucus serratus)

Descripción: Fucus serratus es un alga marina del norte del Océano Atlántico, conocido como alga dentada o serrada. Es de color oliva y similar a F. vesiculosus y F. spiralis. Crece desde un rizoide. Las hojas son planas, de unos 2 cm de ancho, bifurcadas, y hasta 1 m de largo incluyendo un corto estípite. La hoja aplanada tiene un nervio central distinta y se distingue fácilmente de taxones relacionados por el borde dentado de las frondas. No tiene vesículas de aire, tal como se encuentran en F. vesiculosus, ni está retorcida en espiral como F. spiralis.

Dos hojas de Laminaria digitata varadas en Anglesey, Gales, Reino Unido; es fondo es mayormente Ascophyllum nodosum. Ascophyllum nodosum

Sargazo vejigoso o vesiculoso (Ascophyllum nodosum)

Dónde se encuentra: Es común en la costa noroeste de Europa (desde Svalbard a Portugal), incluyendo el este de Groenlandia y la costa noreste de Norteamérica.

Descripción: Ascophyllum nodosum es un alga comestible del norte del Océano Atlántico. Ascophyllum nodosum tiene hojas largas con grandes vejigas de aire en forma de huevo que figuran en las hojas a intervalos regulares y no acechadas. Las hojas pueden alcanzar 2 m de longitud. Ellas están unidas por un rizoide a las rocas y peñas. Las hojas son de color oliva y algo comprimidas pero sin un nervio central. Esta alga crece muy lentamente y puede vivir durante varias décadas; puede tardar aproximadamente cinco años antes de convertirse en fértil.

Alga Roja

Musgo de Irlanda (Chondrus crispus)

Dónde se encuentra: Chondrus crispus crece en abundancia a lo largo de la parte rocosa de la costa atlántica de Europa y Norteamérica. También se puede encontrar en el norte del Océano Pacífico y en partes del Mediterráneo.

Descripción: Chondrus crispus es una pequeña alga roja un poco más de 20 cm de largo que crece de un rizoide y se divide de una forma dicotómica, en forma de abanico cuatro o cince veces. La morfología es variable, especialmente la amplitud de los talos. Las ramas son 2 a 15 mm de ancho, firme en la textura y el color de rojizo oscuro hasta amarillenta en la luz del sol. En su condición fresca, son suaves y cartilaginosas, que varían en color desde un amarillo verdoso a un morado o púrpura-marrón oscuro; pero cuando se lavan y se secan al sol para su conservación tiene un aspecto y consistencia amarillento, como cuerno y translúcido. El constituyente principal de musgo irlandés es un cuerpo mucilaginoso, de la que contiene aproximadamente 55%; la planta también consiste casi el 10% de proteínas y un 15% de la materia mineral, y es rica en yodo y azufre. Cuando ablandado en agua, tiene un olor como el mar y, debido a la abundante mucílago, forma una gelatina cuando se hierve, que contiene de 20 a 30 veces su peso de agua. Musgo irlandés es un fuente importante de carragenina, que se utiliza comúnmente como un espesante y estabilizador en productos lácteos tales como helados y alimentos procesados.

Nori (Porphyra)

Descripción: Porphyra is a foliose red algal genus of laver, comprising approximately 70 species. It grows in the intertidal, typically between the upper intertidal to the splash zone. In East Asia, is used to produce the sea vegetable products nori (in Japan) and gim (in Korea), the most commonly eaten seaweed. It is considered that there are 60 to 70 species of Porphyra worldwide and seven in the British Isles. Porphyra es un foliose género de algas rojas que comprende de aproximadamente 70 especies. Crece en la zona intermareal, normalmente entre el intermareal superior a la zona de chapoteo. En Asia oriental, se utiliza para producir los productos vegetales de mar nori (en Japón) y gim (en Corea), el alga más consumida. Se considera que hay entre 60 a 70 especies de Porphyra en todo el mundo y siete en las Islas Británicas.

Referencias

- Seaweed Lady on Flickr tiene muchas fotos de varias algas marinas.

- http://www.csd509j.net/cvhs/berand/Marine2007-2008/Labs/Student%20Pressing%20Algae%20Lab.doc - información en secar y montar algas marinas (sólo disponible en inglés)