AY Honors/Horse Husbandry/Answer Key

1. What line of profit is derived by the use of specially-selected mares?

The primary line of profit derived from a specially-selected mare is breeding her and selling the offspring.

However, making a profit in horse breeding is often difficult. While some owners of only a few horses may keep a foal for purely personal enjoyment, many individuals breed horses in hopes of making some money in the process.

The minimum cost of breeding for a mare owner includes the stud fee, and the cost of proper nutrition, management and veterinary care of the mare throughout gestation, parturition, and care of both mare and foal up to the time of weaning. Veterinary expenses may be higher if specialized reproductive technologies are used or health complications occur.

A general rule of thumb is that a foal intended for sale should be worth three times the cost of the stud fee if it were sold at the moment of birth. From birth forward, the costs of care and training are added to the value of the foal, with a sale price going up accordingly. If the foal wins awards in some form of competition, that may also enhance the price.

On the other hand, without careful thought, foals bred without a potential market for them may wind up being sold at a loss, and in a worst-case scenario, sold for "salvage" value -- a euphemism for sale to slaughter as horsemeat.

Therefore, a mare owner must consider their reasons for breeding, asking hard questions of themselves as to whether their motivations are based on either emotion or profit and how realistic those motivations may be.

2. Why is it preferable to raise purebred colts rather than common grades?

If the breeding endeavor is intended to make a profit, there are market factors to consider which may vary considerably from year to year, from breed to breed, and by region of the world. In many cases, the low end of the market is saturated with horses, and the law of supply and demand thus allows little or no profit to be made from breeding unregistered animals or animals of poor quality, even if registered.

3. Name at least five points that are desirable in selecting a horse.

- Conformation - how well does the horse meet the standards specified for its breed?

- Temperament - this describes how gentle or spirited a horse is.

- Sport - does it fit with what you want to do?

- Training - unless you intend to train the horse yourself, you should get one that has already been trained.

- Health History - has the horse been plagued with health problems? Were its parents and siblings healthy?

4. What type of training will help colts to grow into gentle, dependable horses?

Most young domesticated horses are handled at birth or within the first few days of life, though some are only handled for the first time when they are weaned from their mothers, or dams. Advocates of handling foals from birth sometimes use the concept of imprinting to introduce a foal within its first few days and weeks of life to many of the activities they will see throughout their lives. Within a few hours of birth, a foal being imprinted will have a human touch it all over, pick up its feet, and introduce it to human touch and voice.

Others may leave a foal alone for its first few hours or days, arguing that it is more important to allow the foal to bond with its dam. However, even people who do not advocate imprinting often still place value on handling a foal a great deal while it is still nursing and too small to easily overpower a human. By doing so, the foal ideally will learn that humans will not harm it, but also that humans must be respected.

While a foal is far too young to be ridden, it is still able to learn skills it will need later in life. By the end of a foal's first year, it should be halter-broke, meaning that it allows a halter placed upon its head and has been taught to be led by a human at a walk and trot, to stop on command and to stand tied. The young horse needs to be calm for basic grooming, as well as veterinary care such as vaccinations and worming. A foal needs regular hoof care and can be taught to stand while having its feet picked up and trimmed by a farrier. Ideally a young horse should learn all the basic skills it will need throughout its life, including: being caught from a field, loaded into a horse trailer, and not to fear flapping or noisy objects. It also can be exposed to the noise and commotion of ordinary human activity, including seeing motor vehicles, hearing radios, and so on. More advanced skills sometimes taught in the first year include learning to accept blankets placed on it, to be trimmed with electric clippers, and to be given a bath with water from a hose. The foal may learn basic voice commands for starting and stopping, and sometimes will learn to square its feet up for showing in in-hand or conformation classes. If these tasks are completed, the young horse will have no fear of things placed on its back, around its belly or in its mouth.

Some people, whether through philosophy or simply due to being pressed for time, do not handle foals significantly while they are still nursing, but wait until the foal is weaned from its dam to begin halter breaking and the other tasks of training a horse in its first year. The argument for gentling and halter-breaking at weaning is that the young horse, in crisis from being separated from its dam, will more readily bond with a human at weaning than at a later point in its life. Sometimes the tasks of basic gentling are not completed within the first year but continue when the horse is a yearling. Yearlings are larger and more unpredictable than weanlings, plus often are easily distracted, in part due to the first signs of sexual maturity. However, they also are still highly impressionable, and though very quick and agile, are not at their full adult strength.

Rarer, but not uncommon even in the modern world, is the practice of leaving young horses completely unhandled until they are old enough to be ridden, usually between the age of two and four, and completing all ground training as well as training for riding at the same time. However, waiting until a horse is full grown to begin training is often far riskier for humans and requires considerably more skill to avoid injury.

5. Describe the proper care and feeding of horses and give three different types of food for horses.

Living environment

Worldwide, horses and other equids usually live outside with access to shelter from the elements. In some cases, animals are kept in a barn or stable, or may have access to a shed or shelter. Horses require both shelter from wind and precipitation, as well as room to exercise and run. They must have access to clean fresh water at all times, and access to adequate forage such as grass or hay. In the winter, horses grow a heavy hair coat to keep warm and usually stay warm if well-fed and allowed access to shelter.

Pastures

Horses require room to exercise. If a horse is kept in a pasture, the amount of land needed for basic maintenance varies with climate, an animal needs more land for grazing in a dry climate than in a moist one. However, an average of between one and three acres of land per horse will provide adequate forage in much of the world, though feed may have to be supplemented in winter or during periods of drought. To lower the risk of laminitis, horses also may need to be removed from lush, rapidly changing grass for short periods in the spring and fall (autumn), when the grass is particularly high in non-structural carbohydrates.

Grooming

Horses groomed regularly have healthier and more attractive coats. Many horse management handbooks recommend grooming a horse daily, though for the average modern horse owner, this is not always possible. However, a horse should always be groomed before being ridden to avoid chafing and rubbing of dirt and other material, which can cause sores on the animal and also grind dirt into horse tack. Grooming also allows the horse handler to check for injuries and is a good way to gain the trust of the animal.

Veterinary care

There are many disorders that affect horses, including colic, laminitis, and internal parasites. Horses also can develop various infectious diseases that can be prevented by routine vaccination. It is sensible to register a horse or pony with a local equine veterinarian, in case of emergency. The veterinary practice will keep a record of the owner's details and where the horse or pony is kept, and any medical details. It is considered best practice for a horse to have an annual checkup, usually in the spring. Some practitioners recommend biannual checkups, in the spring and fall.

Parasite management

All horses and ponies have a parasite burden, and therefore treatment is periodically needed throughout the horse or pony's life. Some steps to reduce parasite infection include regularly removing droppings from the horse's stall, shed or field; breaking up droppings in fields by harrowing or disking; minimizing crowding in fields; periodically leaving a field empty for several weeks; or placing animals other than horses on the field for a period of time. If botflies are active, fly spray may repel insects, but needs frequent reapplication to remain effective. A small pumice stone or dull knife may be carefully used to scrape off any bot eggs that are stuck on the horse. (Bot eggs are yellow and roughly the size of a grain of sand, they are clearly visible on dark hair, harder to spot on white hair.)

However, worms cannot be completely eliminated. Therefore, most modern horse owners commonly give anthelmintic drugs (wormers) to their horses to reduce these parasites.

Dental care

A horse's teeth grow continuously throughout its life and can develop uneven wear patterns. Most common are sharp edges on the sides of the molars which may cause problems when eating or being ridden. For this reason a horse or pony needs to have its teeth checked by a veterinarian or qualified equine dentist at least once a year. If there are problems, any points, unevenness or rough areas can be ground down with a rasp until they are smooth. This process is known as "floating".

Types of food

Horses can consume approximately 2% to 2.5% of their body weight in dry feed each day. Therefore, a 1,000 lb (450 kg). adult horse could eat up to 25 pounds of food. Foals less than six months of age eat 2 to 4% of their weight each day.

Solid feeds are placed into three categories: forages (such as hay and grass), concentrates (including grain or pelleted rations), and supplements (such as prepared vitamin or mineral pellets). Equine nutritionists recommend that 50% or more of the animal's diet by weight should be forages. If a horse is working hard and requires more energy, the use of grain is increased and the percentage of forage decreased so that the horse obtains the energy content it needs for the work it is performing. However, forage amount should never go below 1% of the horse's body weight per day.

6. Know the following:

a. Halter

Horse halters are sometimes confused with a bridle. The primary difference between a halter and a bridle is that a halter is used by a handler on the ground to lead or tie up an animal, but a bridle is generally used by a person who is riding or driving an animal that has been trained in this use. A halter is safer than a bridle for tying, and in fact, a horse should never be tied with a bridle. On the other hand, a bridle offers more control when riding.

b. Bridle

A bridle is a piece of equipment used to control a horse. The bridle fits over a horse's head, and has the purpose of controlling the horse. It holds a bit in the horse's mouth. Headgear without a bit that uses a noseband to control a horse is called a hackamore, or, in some areas, a bitless bridle. There are many different designs with many different name variations, but all use a noseband that is designed to exert pressure on sensitive areas of the animal's face in order to provide direction and control.

Parts of the Bridle

The bridle consists of the following elements:

- Crownpiece

- The crownpiece, headstall (US) or headpiece (UK) goes over the horse's head just behind the animal's ears, at the poll. It is the main strap that holds the remaining parts of the bridle in place.

- Cheekpieces

- On most bridles, two cheekpieces attach to either side of the crownpiece and run down the side of the horse's face, along the cheekbone and attach to the bit rings. On some designs, the crownpiece is a longer strap that includes the right cheekand crownpiece as a single unit and only a left side cheekpiece is added.

- Throatlatch

- the throatlatch (US) or throatlash (UK) is usually part of the same piece of leather as the crownpiece. It runs from the horse's right ear, under the horse's throatlatch, and attaches below the left ear. The main purpose of the throatlatch is to prevent the bridle from coming off over the horse's head, which can occur if the horse rubs its head on an object, or if the bit is low in the horse's mouth and tightened reins raise it up, loosening the cheeks.

- Browband

- The crownpiece runs through the browband. The browband runs from just under one ear of the horse, across the forehead, to just under the other ear. It prevents the bridle from sliding behind the poll onto the upper neck, and holds multiple headstalls together when a cavesson or second bit is added, and holds the throatlatch in place on designs where it is a separate strap. In certain sports, such as dressage and Saddle seat, decorative browbands are sometimes fashionable.

- Noseband

- the noseband encircles the nose of the horse. It is often used to keep the animal's mouth closed, or to attach other pieces or equipment, such as martingales. See also Noseband.

- Cavesson

- The cavesson is a specific type of noseband used on English bridles wherein the noseband is attached to its own headstall, held onto the rest of the bridle by the browband. Because it has a separate headstall (also called sliphead), a cavesson can be adjusted with greater precision; a noseband that is simply attached to the same cheekpieces that hold the bit cannot be raised or lowered. In Saddle seat riding, the cavesson is often brightly colored and matches the browband. Variations on the standard English-style bridle are often named for their style of noseband. For use in polo, a gag bridle usually has a noseband plus a cavesson.

- Reins

- The reins of a bridle attach to the bit, below the attachment for the cheekpieces. The reins are the rider's link to the horse, and are seen on every bridle. Reins are often laced, braided, have stops, or are made of rubber or some other tacky material to provide extra grip.

- Bit

- The bit goes into the horse's mouth, resting on the sensitive interdental space between the horse's teeth known as the "bars."

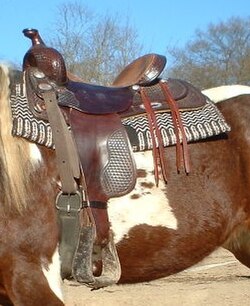

c. Saddle

Parts of an equestrian saddle:

- Tree

- the base on which the rest of the saddle is built. Usually based on wood or a similar synthetic material, it is eventually covered in leather or a leatherlike synthetic. The tree size determines its fit on the horse's back as well as the size of the seat for the rider.

- Seat

- the part of the saddle where the rider sits, it is usually lower than the pommel and cantle to provide security

- Pommel or Pomnel (English)/ Swells (Western)

- the front, slightly raised area of the saddle.

- Cantle

- the back of the saddle

- Stirrup

- part of the saddle in which the rider's feet go, provides support and leverage to the rider.

- Leathers and Flaps (English) or Fenders (Western)

- The leather straps connecting the stirrups to the saddle tree and protecting the rider's legs from sweat.

- D-ring

- a "D"-shaped ring on the front of a saddle, to which certain pieces of equipment (such as breastplates) can be attached.

- Girth or Cinch

- A strap that goes around the horse's barrel that holds the saddle in place.

7. Know how to properly put a halter, bridle, and saddle on a horse.

8. Know how to properly care for the hoofs of a horse. Know the parts of the hoof.

Hoof care

The hooves of a horse or pony are cleaned by being picked out with a hoof pick to remove any stones, mud and dirt and to check that the shoes (if worn) are in good condition. Keeping feet clean and dry wherever possible helps prevent both lameness as well as hoof diseases such as thrush (a hoof fungus). The feet should be cleaned every time the horse is ridden, and if the horse is not ridden, it is still best practice to check and clean feet frequently. Daily cleaning is recommended in many management books, but in practical terms, a weekly hoof check of healthy horses at rest is often sufficient during good weather.

Use of hoof oils, dressings, or other topical treatments varies by region, climate, and the needs of the individual horse. Many horses have healthy feet their entire lives without need for any type of hoof dressing. While some horses may have circumstances where a topical hoof treatment is of benefit, improper use of dressings can also create hoof problems, or make a situation worse instead of better. Thus, there is no universal set of guidelines suitable for all horses in all parts of the world. Farriers and veterinarians in a horse owner's local area can provide advice on the use and misuse of topical hoof dressings, offering suggestions tailored for the needs of the individual horse.

Horses and ponies require routine hoof care by a professional farrier every 6 to 8 weeks, depending on the animal, the work it performs and, in some areas, weather conditions. Hooves usually grow faster in the spring and fall than in summer or winter. They also appear to grow faster in warm, moist weather than in cold or dry weather. In damp climates, the hooves tend to spread out more and wear down less than in dry climates, though more lush, growing forage may also be a factor. Thus, a horse kept in a climate such as that of Ireland may need to have its feet trimmed more frequently than a horse kept in a drier climate such as Arizona, in the southwestern United States.

All domesticated horses need regular hoof trims, regardless of use. Horses in the wild do not need hoof trims because they travel as much as 50 miles a day in dry or semi-arid grassland in search of forage, a process that wears their feet naturally. Domestic horses in light use are not subjected to such severe living conditions and hence their feet grow faster than they can be worn down. Without regular trimming, their feet can get too long, eventually splitting, chipping and cracking, which can lead to lameness.

On the other hand, horses subjected to hard work may need horseshoes for additional protection. Some advocates of the barefoot horse movement maintain that proper management may reduce or eliminate the need for shoes, but certain activities, such as horse racing and police horse work, create unnatural levels of stress and will wear down hooves faster than they would in nature. Thus, some types of working horses almost always require some form of hoof protection.

The cost of farrier work varies widely, depending on the part of the world, the type of horse to be trimmed or shod, and any special issues with the horse's foot that may require more complex care. The cost of a trim is roughly half to one-third that of the cost of a set of shoes, and professional farriers are typically paid at a level commensurate with other skilled laborers in an area, such as plumbers or electricians, though farriers charge by the horse rather than by the hour.

In the United Kingdom, it is illegal for anyone else other than a registered farrier to shoe a horse or prepare a foot for the immediate reception of a shoe. The farrier should have any one of the following qualifications, the FWCF being the most highly skilled:

- DipWCF (Diploma of the Worshipful Company of Farriers)

- AWCF (Associateship of the Worshipful Company of Farriers)

- FWCF (Fellowship of the Worshipful Company of Farriers)

In the USA, there are no legal restrictions on who may do farrier work. However, trained and qualified farriers usually belong to professional organizations such as: the AFA (American Farrier's Association), which certifies farriers as Intern, Journeyman, and Certified Farrier.

Parts of the hoof

9. Care for a colt or horse for at least one week.

There are many ways to meet this requirement. If you own a horse, you will obviously have ample opportunity to care for it for a week (just make sure you really do, and don't just rely on mom, dad, or another relative to do it for you).

But it is far more common to not own your own horse. In that case, you will need to explore other options. If you have friends or relatives with a horse, they may welcome you to stay with them for a week during the summer in exchange for your caring for their horse. Unless they live very close to you, it is probably not realistic to commute to their stable and properly care for the animal. You really need to live on the farm to fully experience this aspect of the honor.

Another option is to attend one of many available "horse camps" - summer camp programs dedicated to the equestrian arts. Many of these are set up specifically for girls only, or for children over the age of 13, etc., so you will want to check that they will accept you before applying. However, they may be able to recommend another horse camp. Unfortunately, these programs are usually not cheap, so you may need to raise a substantial sum of money before you can attend. It might help to let your relatives know that you would like any birthday or Christmas gifts to be in the form of money set aside for this purpose, or you may be able to take on several odd jobs (shoveling horse stalls or putting up hay are ideas that come to mind). But don't limit your potential to equestrian-related jobs only.

If you really love horses and know a lot about them, you may be able to get a job at a horse camp. It doesn't hurt to ask!

References

Much of the material for this chapter was taken verbatim from the following Wikipedia articles: