AY Honors/Masonry/Answer Key

1. Name at least six materials commonly used by masons in the erection of walls or buildings.

Primary materials include:

- Brick

- Concrete Block (also known as cinder block)

- Poured Concrete

- Stone

- Glass Block

- Tile

Secondary materials include

- Mortar

- Rebar

- Grout

2. Demonstrate ability to use properly the following:

- Level1.jpg

Level

- Line stretcher.jpg

Line Stretcher

- Masons jointer.jpg

S-Tool (jointer)

Plumb line

A plumb line is a string with a plumb bob at the end of it. The plumb bob hangs straight down, so the plumb line can be used to make sure that a wall is perfectly vertical and does not lean in any direction. A perfectly vertical line is said to be plumb.

Line stretcher (chicken legs)

A line stretcher is used for guiding the mason when laying brick or other materials in a straight line. Typically, the mason will build up the corners or ends of a wall first, stretch a line between them, and lay the remaining bricks between them. The line stretcher is often set about a sixteenth of an inch away from the wall so that the bricks do not touch it (otherwise they might push the line out).

Level

A spirit level or bubble level is an instrument designed to indicate whether a surface is level or plumb. Spirit levels feature a slightly curved glass tube which is incompletely filled with a liquid, usually coloured 'spirit' (a synonym for ethanol), leaving a bubble in the tube. Ethanol is used because of its low freezing point, −114°C, which prevents it from freezing in cold weather. Most commonly spirit levels are employed to indicate how horizontal (level) or how vertical (plumb) a surface is.

Trowel

A trowel is used for applying mortar to bricks, blocks, or other material. It is also used for "throwing a mortar line" - that is, laying a line of mortar atop the surface upon which that the bricks will be laid.

S-tool

An S-Tool is more commonly known as a jointer. The purpose of the S-tool is to place the grooves in the mortar between bricks. The concave grooves seen within the mortar lines of bricks are placed there by scraping the S-tool along the mortar well before it sets.

The S-tool should be used sometime between the time that the mortar is placed, and when it begins to harden. If the S-tool is used too late, then it will result in uneven lines throughout the mortar. The mortar will not have a smooth concave surface, and will look very raggedy.

Sometimes an S-tool is not used, and the mortar is placed on in excess; the slapping of the bricks causes it to drip down over the bricks, and it has a very nice effect when the bricks are painted afterwards.

Mason's hammer

A Mason's hammer has one flat traditional face and a short or long chisel-shaped blade. It can thus be used to chip off edges or small pieces of stone without using a separate chisel. The chisel blade can also be used to rapidly cut bricks or cinder blocks.

3. Demonstrate a knowledge of building cement characteristics (know how to prevent sweating, cracking, shrinking, crumbling, and loss of strength).

- Sweating

- Cracking

- Shrinking

- Crumbling

- Loss of strength

4. Make useable mortar and state proper proportions of ingredients (lime, sand, etc.).

There are two basic types of mortar: type N and type S.

Type N mortar is used for interior work and exterior work that is above grade (that is, not buried). It is made by combining:

- Lime (one part)

- Cement (one part)

- Sand (six parts)

Type S mortar is used for below-grade applications such as retaining walls and basements. It is made by combining:

- Lime (one part)

- Cement (two parts)

- Sand (nine parts)

Water is added to either of these mixtures and worked in with a trowel or a hoe until it reaches the desired consistency. Both types can be purchased pre-mixed so the mason need only add the water. Mixing is done on a hard flat surface, often in a wheelbarrow or on a sheet of plywood, but more properly in a mortar box.

5. Lay a straight stone, brick, or block masonry wall at least four feet (1.2 meters) high and ten feet (3.0 meters) long, including an inside or outside corner (surface must be struck and broomed).

Stone

Brick

Good bricklaying procedure depends on good workmanship and efficiency. Efficiency involves doing the work with the fewest possible motions. Each motion should have a purpose and should accomplish a definite result. After learning the fundamentals, every builder should develop methods for achieving maximum efficiency. The work must be arranged in such a way that the Builder is continually supplied with brick and mortar. The scaffolding required must be planned before the work begins. It must be built in such a way as to cause the least interference with other crewmembers.

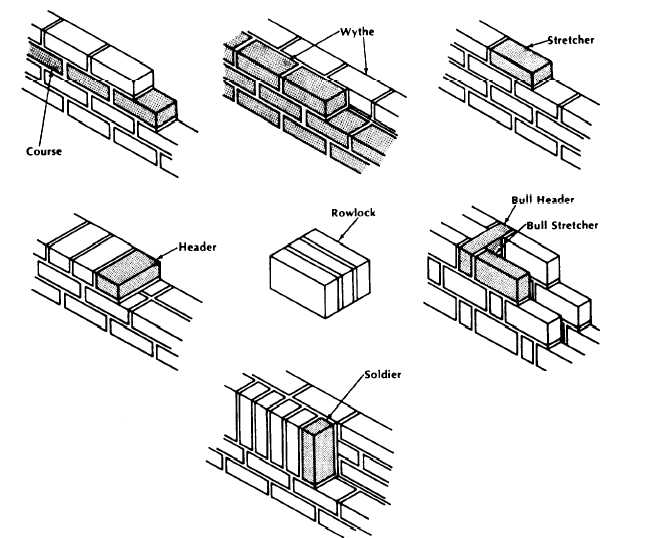

To efficiently and effectively lay bricks, you must be familiar with the terms that identify the position of masonry units and mortar joints in a wall. The following list, which is referenced in Figure 1, provides some of the basic terms you will encounter.

- Course

- One of several continuous, horizontal layers (or rows) of masonry units bonded together.

- Wythe

- Each continuous, vertical section of a wall, one masonry unit thick. Sometimes called a tier.

- Stretcher

- A masonry unit laid flat on its bed along the length of a wall with its face parallel to the face of the wall.

- Header

- A masonry unit laid flat on its bed across the width of a wall with its face perpendicular to the face of the wall. Generally used to bond two wythes.

- Row lock

- A header laid on its face or edge across the width of a wall.

- Bull header

- A rowlock brick laid with its bed perpendicular to the face of the wall.

- Bull stretcher

- A rowlock brick laid with its bed parallel to the face of the wall.

- Soldier

- A brick laid on its end with its face perpendicular to the face of the wall.

Bonds

The term “bond” as used in masonary has three different meanings: structural bond, mortar bond, or pattern bond. Structural bond refers to how the individual masonry units interlock or tie together into a single structural unit. You can achieve structural bonding of brick and tile walls in one of three ways:

- Overlapping (interlocking) the masonry units

- Embedding metal ties in connecting joints

- Using grout to adhere adjacent wythes of masonry.

Mortar bond refers to the adhesion of the joint mortar to the masonry units or to the reinforcing steel. Pattern bond refers to the pattern formed by the masonry units and mortar joints on the face of a wall. The pattern may result from the structural bond, or may be purely decorative and unrelated to the structural bond. Figure 2 shows the six basic pattern bonds in common use today: running, common or American, Flemish, English, stack, and English cross or Dutch bond.

The running bond is the simplest of the six patterns, consisting of all stretchers. Because the bond has no headers, metal ties usually form the structural bond.

The common, or American, bond is a variation of the running bond, having a course of full-length headers at regular intervals that provide the structural bond as well as the pattern. Header courses usually appear at every fifth, sixth, or seventh course, depending on the structural bonding requirements. You can vary the common bond with a Flemish header course. In laying out any bond pattern, be sure to start the corners correctly. In a common bond, use a three-quarter closure at the corner of each header course.

In the Flemish bond, each course consists of alternating headers and stretchers. The headers in every other course center over and under the stretchers in the courses in between. The joints between stretchers in all stretcher courses align vertically. When headers are not required for structural bonding, you can use bricks called blind headers. You can start the corners in two different ways. In the Dutch corner, a three-quarter closure starts each course. In the English corner, a 2-inch or quarter closure starts the course.

The English bond consists of alternating courses of headers and stretchers. The headers center over and under the stretchers. However, the joints between stretchers in all stretcher courses do not align vertically. You can use blind headers in courses that are not structural bonding courses.

The stack bond is purely a pattern bond, with no overlapping units and all vertical joints aligning. You must use dimensionally accurate or carefully rematched units to achieve good vertical joint alignment. You can vary the pattern with combinations and modifications of the basic patterns shown above. This pattern usually bonds to the backing with rigid steel ties or 8-inch-thick stretcher units when available. In large wall areas or load-bearing construction, insert steel pencil rods into the horizontal mortar joints as reinforcement.

The English cross or Dutch bond is a variation of the English bond. It differs only in that the joints between the stretchers in the stretcher courses align vertically. These joints center on the headers in the courses above and below.

When a wall bond has no header courses, use metal ties to bond the exterior wall brick to the backing courses. Figure 3 shows three typical metal ties.

Install flashing at any spot where moisture is likely to enter a brick masonry structure. Flashing diverts the moisture back outside. Always install flashing under horizontal masonry surfaces, such as sills and copings; at intersections between masonry walls and horizontal surfaces, such as a roof and parapet or a roof and chimney; above openings (doors and windows, for example); and frequently at floor lines, depending on the type of construction. The flashing should extend through the exterior wall face and then turn downward against the wall face to form a drop.

You should provide weep holes at intervals of 18 to 24 inches to drain water to the outside that might accumulate on the flashing. Weep holes are even more important when appearance requires the flashing to stop behind the wall face instead of extending through the wall. This type of concealed flashing, when combined with tooled mortar joints, often retains water in the wall for long periods and, by concentrating the moisture at one spot, does more harm than good.

Mortar Joints and Pointing

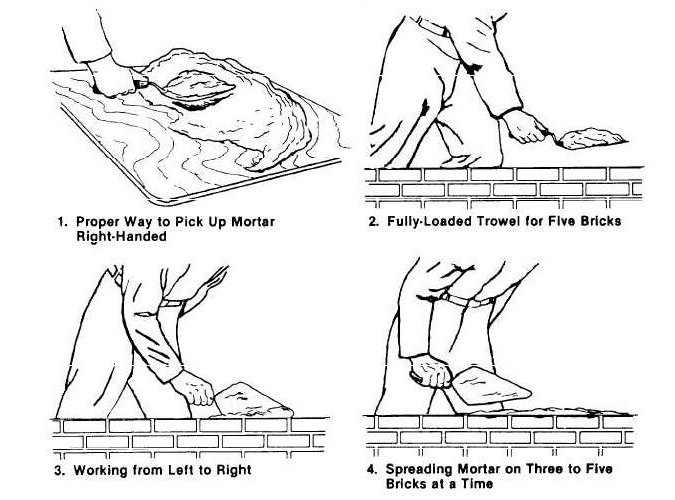

There is no set rule governing the thickness of a brick masonry mortar joint. Irregularly shaped bricks may require mortar joints up to 1/2 inch thick to compensate for the irregularities. However, mortar joints 1/4 inch thick are the strongest. Use this thickness when the bricks are regular enough in shape to permit it. A slushed joint is made simply by depositing the mortar on top of the head joints and allowing it to run down between the bricks to form a joint. You cannot make solid joints this way. Even if you fill the space between the bricks completely, there is no way you can compact the mortar against the brick faces; consequently a poor bond results. The only effective way to build a good joint is to trowel it. The secret of mortar joint construction and pointing is in how you hold the trowel for spreading mortar.

Figure 4 shows the correct way to hold a trowel. Hold it firmly in the grip shown, with your thumb resting on top of the handle, not encircling it. If you are right-handed, pick up mortar from the outside of the mortar board pile with the left edge of your trowel. You can pick up enough to spread one to five bricks, depending on the wall space and your skill. A pickup for one brick forms only a small pile along the left edge of the trowel. A pickup for five bricks is a full load for a large trowel.

If you are right-handed, work from left to right along the wall. Holding the left edge of the trowel directly over the center line of the previous course, tilt the trowel slightly and move it to the right (view 3), spreading an equal amount of mortar on each brick until you either complete the course or the trowel is empty (view 4). Return any mortar left over to the mortar board.

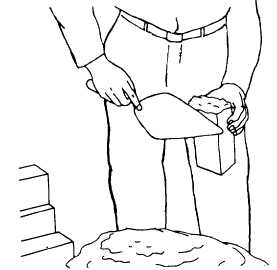

Do not spread the mortar for a bed joint too far ahead of laying - four or five brick lengths is best. Mortar spread out too far ahead dries out before the bricks become bedded and causes a poor bond. The mortar must be soft and plastic so that the brick will bed in it easily. Spread the mortar about 1 inch thick and then make a shallow furrow in it (Figure 7, view 1). A furrow that is too deep leaves a gap between the mortar and the bedded brick. This reduces the resistance of the wall to water penetration. Using a smooth, even stroke, cut off any mortar projecting beyond the wall line with the edge of the trowel (view 2). Retain enough mortar on the trowel to butter the left end of the first brick you will lay in the fresh mortar. Throw the rest back on the mortar board. Pick up the first brick to be laid with your thumb on one side of the brick and your fingers on the other. Apply as much mortar as will stick to the end of the brick and then push it into place (Figure 8). Squeeze out the excess mortar at the head joint and at the sides. Make sure the mortar completely fills the head joint (Figure 9). After bedding the brick, cut off the excess mortar and use it to start the next end joint. Throw any surplus mortar back on the mortar board where it can be restored to workability.

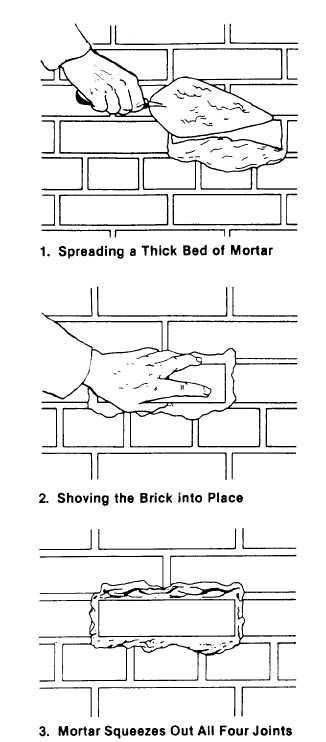

Figure 10 shows how to insert a brick into a space left in a wall. First, spread a thick bed of mortar (view 1), and then shove the brick into the wall space (view 2) until mortar squeezes out of all four joints (view 3). This way, you know that the joints are full of mortar at every point. To make a cross joint in a header course, spread the bed joint mortar several brick widths in advance. Then, spread mortar over the face of the header brick before placing it in the wall (Figure 11, view 1). Next, shove the brick into place, squeezing out mortar at the top of the joint. Finally, cut off the excess mortar as shown in view 2.

Figure 12 shows how to lay a closure brick in a header course. First, spread about 1 inch of mortar on the sides of the brick already in place (view 1), as well as on both sides of the closure brick (view 2). Then, lay the closure brick carefully into position without disturbing the brick already laid (view 3). If you do disturb any adjacent brick, cracks will form between the brick and mortar, allowing moisture to penetrate the wall. You should place a closure brick for a stretcher course (Figure 13) using the same techniques as for a header course. As we mentioned earlier, filling exposed joints with mortar immediately after laying a wall is called pointing. You can also fill holes and correct defective mortar joints by pointing, using a pointing trowel.

Block

Planning

The first step in laying a block wall is to carefully plan the project. When using concrete block to build a wall, it is important to select the dimensions of the wall based on the size of the block. Standard concrete blocks are 7 5/8" wide, 7 5/8" deep, and 15 5/8" long. Assuming that the mortar joint is 3/8" thick brings the block plus mortar dimensions to 8x8x16". You will want the outside dimension of the wall to be a multiple of a half-block length (minus one mortar joint) so that you do not have to cut blocks to a custom size. The height of the wall should also be a multiple of the block height (including the mortar joint).

Steps in Construction

The first step in building a concrete masonry wall is to locate the corners of the structure. In locating the corners, you should also make sure the footing or slab formation is level so that each builder starts each section wall on a common plane. This also helps ensure that the bed joints are straight when the sections are connected. If the foundation is badly out of level, the entire first course should be laid before builders begin working on other courses. If this is not possible, a level plane should be established with a transit or engineer’s level. The second step is to chase out bond, or lay out, by placing the first course of blocks without mortar (Figure 13, view 1).

Snap a chalk line to mark the footing and align the blocks accurately. Then, use a piece of material 3/8 inch thick to properly space the blocks. This helps you get an accurate measurement. The third step is to replace the loose blocks with a full mortar bed, spreading and furrowing it with a trowel to ensure plenty of mortar under the bottom edges of the first course (figure 14, view 2). Carefully position and align the corner block first (view 3 of figure 14). Lay the remaining first-course blocks with the thicker end up to provide a larger mortar-bedding area. For the vertical joints, apply mortar only to the block ends by placing several blocks on end and buttering them all in one operation (view 4). Make the joints 3/8 inch thick. Then, place each block in its final position, and push the block down vertically into the mortar bed and against the previously laid block. This ensures a well-tilled vertical mortar joint (view 5). After laying three or four blocks, use a mason’s level as a straightedge to check correct block alignment (figure 16, view 1). Then, use the level to bring the blocks to proper grade and plumb by tapping with a trowel handle as shown in view 2. Always lay out the first course of concrete masonry carefully and make sure that you properly align, level, and plumb it. This assures that succeeding courses and the final wall are both straight and true.

Next

6. Pour a level footing, using hand mixed cement and proper reinforcement.

7. Make the forms and lay a piece of concrete walk or floor, using commercially mixed cement. Finish it and rule it.

8. Write a paragraph describing the behavior of cement; that is, its reaction to water, its adhesive qualities, how long it takes to set, etc.

Historical Notes

Masonry was introduced in 1937, discontinued in 1956, and revised and reintroduced in 1986.

References

Much of the material outlined in requirement 5 was taken verbatim from the U.S. Navy's training manual NAVEDTRA 14043. Since this manual is an original work of the U.S. Federal goverment, it is in the public domain, meaning it is legal (and ethical) to use it for any purpose (including providing the excellent instruction for this difficult requirement).