Difference between revisions of "AY Honors/Birds - Advanced/Answer Key"

m (1 revision from w:Birdwatching) |

m (- Category of AYHAB) |

||

| (48 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{HonorSubpage}} | |

| + | <section begin="Body" /> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=1}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:59--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | <!-- 1. Have the Birds honor. --> | ||

| + | {{honor_prerequisite|honor=Birds}} | ||

| − | + | <!--T:60--> | |

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 1 --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=2}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:61--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | <!-- 2. Know the laws protecting birds in your state, province, or country. --> | ||

| − | == | + | ===United States=== <!--T:53--> |

| − | + | In the United States, birds are protected by a fairly large number of international treaties and domestic laws. These can be categorized as primary and secondary authorities. Primary authorities are international conventions and major domestic laws that focus primarily on migratory birds and their habitats. Secondary authorities are broad-based domestic environmental laws that provide ancillary but significant benefits to migratory birds and their habitats. | |

| − | == | + | ====United States Federal laws that protect bird populations ==== <!--T:4--> |

| − | + | ;The Lacey Act: (passed on May 25, 1900) prohibited game taken illegally in one state to be shipped across state boundaries contrary to the laws of the state where taken. | |

| + | ;Weeks-McLean Law: (which became effective on March 4, 1913) was designed to stop commercial market hunting and the illegal shipment of migratory birds from one state to another. The Act boldly proclaimed that: | ||

| + | :''All wild geese, wild swans, brant, wild ducks, snipe, plover, woodcock, rail, wild pigeons, and all other migratory game and insectivorous birds which in their northern and southern migrations pass through or do not remain permanently the entire year within the borders of any State or Territory, shall hereafter be deemed to be within the custody and protection of the Government of the United States, and shall not be destroyed or taken contrary to regulations hereinafter provided therefor.'' | ||

| − | + | <!--T:5--> | |

| + | ;Migratory Bird Treaty Act: The Migratory Bird Treaty Act is the domestic law that affirms, or implements, the United States' commitment to four international conventions (with Canada, Japan, Mexico, and Russia) for the protection of a shared migratory bird resource. Each of the conventions protect selected species of birds that are common to both countries (i.e., they occur in both countries at some point during their annual life cycle). | ||

| − | + | <!--T:6--> | |

| + | ;Endangered Species Act: The Endangered Species Act is also the domestic law that confirms, or implements, the United States' commitment to two international treaties that contain important provisions for the protection of migratory birds: | ||

| + | :*CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) | ||

| + | :*Pan American Convention (the Convention on Nature Protection and Wildlife Preservation in the Western Hemisphere). | ||

| − | + | <!--T:7--> | |

| − | + | ;Other International Treaties: In additional to the conventions implemented by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and the Endangered Species Act, the United States is party to two other international treaties that afford special protection to migratory birds. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <!--T:8--> | |

| − | + | :* Ramsar Convention (The Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitats) | |

| + | :* Antarctic Treaty (designed to protect the native birds, mammals, and plants of the Antarctic) | ||

| − | + | <!--T:9--> | |

| + | ;Other Domestic Laws: Other domestic laws protecting birds in the United States include: | ||

| + | :* Bald Eagle Protection Act | ||

| + | :* Waterfowl Depredations Prevention Act | ||

| + | :* Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act | ||

| + | :* Wild Bird Conservation Act | ||

| − | + | ====United States Federal Laws protecting bird habitats==== <!--T:10--> | |

| + | ;Duck Stamp Act: The Duck Stamp Act provides a mechanism for generating money for the acquisition and protection of important migratory bird habitats. | ||

| + | ;Wetlands Loan Act: The Wetlands Loan Act, approved October 4, 1961, authorized an advance of funds against future revenues from sale of "duck stamps" as a means of accelerating the acquisition of migratory waterfowl habitat. | ||

| + | ;Emergency Wetlands Resources Act: The Emergency Wetlands Resources Act, approved November 10, 1986, authorized the purchase of wetlands from Land and Water Conservation Fund monies, removing a prior prohibition on such acquisitions. | ||

| + | ;Migratory Bird Conservation Act: The Migratory Bird Conservation Commission was established on February 18, 1929 by the passage of the Migratory Bird Conservation Act. It was created and authorized to consider and approve any areas of land and/or water recommended by the Secretary of the Interior for purchase or rental by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service under the Act, and to fix the price or prices at which such areas may be purchased or rented. In addition to approving purchase and rental prices, the Commission considers the establishment of new waterfowl refuges. | ||

| + | ;North American Wetlands Conservation Act: The North American Wetlands Conservation Act does several things: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <!--T:11--> | ||

| + | :*It encourages partnerships to conserve North American wetland ecosystems for waterfowl, other migratory birds, fish, and wildlife. | ||

| + | :*It encourages the formation of public-private partnerships to develop and implement wetland conservation projects consistent with the North American Waterfowl Management Plan (NAWMP), a blueprint for continental waterfowl and wetlands conservation, and other North American migratory bird conservation agreements. | ||

| + | :*It creates the North American Wetlands Conservation Fund to help support projects through grants. | ||

| + | :*It establishes a nine-member North American Wetlands Conservation Council (Council) to review and recommend grant proposals to the Migratory Bird Conservation Commission for funding. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Canada=== <!--T:54--> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <!--T:55--> | ||

| + | Most species of birds in Canada are protected under the Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994 (MBCA). The MBCA was passed in 1917, and updated in 1994 and 2005, to implement the Migratory Birds Convention, a treaty signed with the United States in 1916. As a result, the Canadian federal government has the authority to pass and enforce regulations [Migratory Birds Regulations (C.R.C., c. 1035)] to protect those species of birds that are included in the Convention. Similar legislation in the United States [Birds Protected By The Migratory Bird Treaty Act] protects birds species found in that country, though the list of bird species protected by each country can be different.<ref>https://ec.gc.ca/nature/default.asp?lang=En&n=496E2702-1</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <!--T:56--> | ||

| + | Each Province and Territory protects a list of bird through legislation usually called the ''Wildlife Act'' (or similar) | ||

| + | |||

| + | <!--T:62--> | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 2 --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=3}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:63--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | <!-- 3. Describe a bird accurately by using standard names for each part of its body. --> | ||

| + | [[Image:Bird.parts.jpg|left|thumb|450px|Parts of a bird's body]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <!--T:13--> | ||

| + | {{clear}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | <!--T:64--> | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 3 --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=4}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:65--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | <!-- 4. Find answers to either a. OR b. --> | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=4a}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:66--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | [[Image:BirdBeaksA.svg|thumb|180px|Gallery of beaks showing various adaptations.]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Female Mallard at Ohio River.jpg|left|thumb|A mallard duck showing her webbed feet.]] | ||

| + | Bird feet have many specializations. For example, perching birds have a tendon locking mechanism in their feet that helps them hold on to the perch when they are asleep. Aquatic birds have webbed feet used for efficient propulsion through the water. Birds of prey have sharp talons on the ends of their feet which they use for capturing and killing their prey. The male emperor penguin's feet are specially shaped so that he can hold an egg on top of them as he covers it with his body to keep it warm. The ostrich has just two toes on each foot (most birds have four), with the nail of the larger, inner one resembling a hoof. The outer toe lacks a nail. This is an adaptation unique to Ostriches that appears to aid in running. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <!--T:15--> | ||

| + | [[Image:Lesser-flamingos.jpg|thumb|left|Flamingos, a wading bird with long legs]] | ||

| + | Their legs are also specialized. Wading birds have long legs to allow them to venture into deeper water in search of fish. The ostrich has large, powerful legs for running (they can reach speeds of 65 km/h (40 mph), the top land speed of any bird. Furthermore, their legs are featherless, which allows them to control their temperature. When it's cold, they can cover their thighs with their wings. When it's hot, they uncover them, allowing them to cool off. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <!--T:16--> | ||

| + | Their beaks are highly specialized as well, adapted for eating insects, grain, coniferous-seeds, nectar, or fruit. They are also adapted to various forms of hunting, including dip netting, surface skimming, mud probing, filter feeding, fishing, or scavenging. | ||

| + | {{clear}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | <!--T:67--> | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 4a --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=4b}} <!--T:17--> | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:68--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=4bi|dispreq=i}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:69--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | Hummingbirds are attracted to many flowering plants. They feed on the nectar of these plants and are important pollinators, especially of deep-throated flowers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <!--T:18--> | ||

| + | They also typically consume more than their own weight in nectar each day, and to do so they must visit hundreds of flowers daily. At any given moment, they are only hours away from starving. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <!--T:19--> | ||

| + | Hummingbirds feed in many small meals, consuming up to their own body weight in nectar and insects per day. They spend an average 10%-15% of their time feeding and 75%-80% sitting, digesting and watching. Obtaining this much food requires a lot of work. Scientists have recorded a Costa's Hummingbirds making 42 feeding flights in 6-5 hours, during which time it visited 1,311 flowers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <!--T:70--> | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 4bi --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=4bii|dispreq=ii}} <!--T:20--> | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:71--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | Hummingbirds are such skillful fliers that they have no fear of predators. They can usually elude them with ease. | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 4bii --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=4biii|dispreq=iii}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:72--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | Most birds move their wings up and down when they fly, but a hummingbird moves its wings front-to-back in a figure-eight pattern. This allows them to generate lift on both the forward and backward strokes, as well as endowing them with the ability to hover and fly backwards. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <!--T:73--> | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 4biii --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=4biv|dispreq=iv}} <!--T:21--> | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:74--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | Ruby-throated Hummingbirds migrate across the Gulf of Mexico, averaging 40 km/h (25 mph). | ||

| + | |||

| + | <!--T:75--> | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 4biv --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=4bv|dispreq=v}} <!--T:22--> | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:76--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | Hummingbirds are known for their ability to hover in mid-air by rapidly flapping their wings 15–80 times per second (depending on the species). Their heart rate can reach as high as 1,260 beats per minute, a rate once measured in a Blue-throated Hummingbird. However, they are capable of slowing down their metabolism at night, or any other time food is not readily available, entering a hibernation-like state known as torpor. During torpor, the heart rate and rate of breathing are both slowed dramatically (the heart rate to roughly 50–180 beats per minute), reducing their need for food. | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 4bv --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=4bvi|dispreq=vi}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:77--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | Hummingbirds' tongues are ''bifurcated'' - a fancy way of saying that like a snake, the hummingbird has a forked tongue. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <!--T:78--> | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 4bvi --> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 4b --> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 4 --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=5}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:79--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | <!-- 5. Identify on a bird's wing the primaries, secondaries, coverts, axillars, and alulae. --> | ||

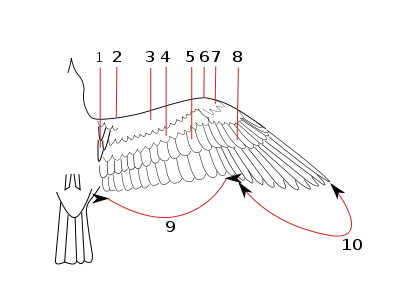

| + | [[Image:Underwing.svg|thumb|400px|1 Axillaries<br> | ||

| + | 2 Margin (Marginal underwing coverts)<br> | ||

| + | 3 Lesser underwing coverts<br> | ||

| + | 4 Median underwing coverts (Secondary coverts)<br> | ||

| + | 5 Greater underwing coverts (Secondary coverts)<br> | ||

| + | 6 Carpal joint<br> | ||

| + | 7 Lesser underwing primary coverts<br> | ||

| + | 8 Greater undering primary coverts<br> | ||

| + | 9 Secondaries<br> | ||

| + | 10 Primaries]] | ||

| + | ;Primaries: | ||

| + | ;Secondaries: | ||

| + | ;Coverts: | ||

| + | ;Axillars: | ||

| + | ;Alulae: The alulea (singular is ''alula'') are small projections on the leading edge of the wing near the carpal joint (6). They are actually one of the bird's digits, and are typically covered with three to five small feathers, with the exact number depending on the species. Like the larger flight feathers found on the wing's trailing edge, these alula feathers are asymmetrical, with the shaft running closer to leading edge. | ||

| + | <br style="clear:both"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <!--T:80--> | ||

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 5 --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=6}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:81--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | <!-- 6. Describe the functions and purposes of bird banding, telling in particular how banding contributes to our knowledge about bird movements. --> | ||

| + | '''Bird banding''' (also known as '''bird ringing''') is an aid to studying wild birds, by attaching a small individually numbered metal or plastic ring to their legs or wings, so that various aspects of the bird's life can be studied by the ability to re-find the same individual later. This can include migration, longevity, mortality, population studies, feeding behavior, and many other aspects. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Terminology and techniques=== <!--T:25--> | ||

| + | [[Image:Mist net kinglet.jpg|thumb|300px|right|A ringed Ruby-crowned Kinglet recaptured in a mist net]] | ||

| + | Those who ring birds are called "bird ringers". Organized banding efforts are called "ringing schemes" and the organizations that run them, "ringing authorities". Birds are "ringed" (rather than "rung"). When a ringed bird is found, and the ring number read and reported back to the ringer or ringing authority, this is termed a "ringing recovery" or "control". | ||

| + | |||

| + | <!--T:26--> | ||

| + | Birds are either ringed at the nest, or after being trapped in fine mist nets, Heligoland traps, drag nets, cannon nets, duck decoys or similar. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <!--T:27--> | ||

| + | A ring of suitable size is attached, and has on it a unique number, plus a contact address. The bird is often weighed and measured, and examined for parasites (which may then be removed) before release. The rings are very light-weight, and have no adverse effect on the birds. The individual birds can then be identified when they are re-trapped, or found dead. | ||

| − | + | <!--T:28--> | |

| + | The finder can contact the address on the ring, give the unique number, and be told the known history of the bird's movements. | ||

| − | + | <!--T:29--> | |

| + | The organizing body, by collating many such reports, can then determine patterns of bird movements for large populations. | ||

| − | + | <!--T:30--> | |

| + | The first organized schemes for bird ringing were started (in 1909) by Arthur Landsborough Thomson in Aberdeen and Harry Witherby in England, though smaller individual marking tests had began some years earlier in Denmark and Germany. | ||

| − | + | ===Similar schemes=== <!--T:31--> | |

| + | ====Wing tags==== | ||

| + | [[Image:Wing tag Great Frigatebird.JPG|thumb|300px|left|This female Great Frigatebird has been tagged with wing tags as part of a breeding study]] | ||

| + | In some surveys, involving larger birds such as eagles, brightly-colored plastic tags are attached to birds' wing feathers. Each has a letter or letters, and the combination of color and letters uniquely identifies the bird. These can then be read in the field, through binoculars, meaning that there is no need to re-trap the birds. Because the tags are attached to feathers, they drop off when the bird moults. '''Imping''' is the practice of replacing a bird's normal feather with a brightly-colored false feather. A '''patagial tag''' is a permanent tag held onto the wing by a rivet punched through the [[W:Patagium|patagium]]. | ||

| − | == | + | ===Radio transmitters and satellite-tracking=== <!--T:32--> |

| + | Where detailed information is needed on an individuals' movements, scientists can fit tiny radio transmitters to birds. For small species the transmitter is carried as a 'backpack' fitted over the wing bases, and for larger species it may be attached to a tail feather or temporary leg band. Both types usually have a tiny (10cm) flexible aerial to improve signal reception. Two field receivers (reading distance and direction) are needed to establish the bird's position using triangulation. Transmitters may be recovered by recapturing the bird or designed to drop off. The technique is useful for tracing individuals during landscape-level movements particularly in dense vegetation (such as tropical forests) and for shy or difficult-to-spot species, because birds can be located from a distance without visual confirmation. | ||

| + | The use of satellite transmitters for bird movements is currently restricted by transmitter size - to species larger than about 400g. They may be attached to migratory birds (geese and swans are popular subjects) or other species undergoing longer-distance flights. Individuals may be tracked by satellites for immense distances, for the lifetime of the transmitter battery. As with wing tags, the transmitters may be designed to drop off when the bird moults; or they may be recovered by recapturing the bird. | ||

| − | + | ====Field-readable rings==== <!--T:33--> | |

| + | A field-readable is a ring or rings, usually made from plastic and brightly colored, which may also have conspicuous markings in the form of letters and/or numbers. They are used by biologists working in the field to identify individual birds without recapture and with a minimum of disturbance to their behavior. | ||

| + | Rings large enough to carry numbers are usually restricted to larger birds, although if necessary small extensions to the rings (leg flags) bearing the identification code allow their use on slightly smaller species. For small species (e.g. most passerines), individuals can be identified by using a combination of small rings of different colors, which are read in a specific order. Most color-marks of this type are considered temporary (the rings degrade, fade and may be lost or removed by the birds) and individuals are usually also fitted with a permanent metal ring. | ||

| − | '' | + | ====Other markers==== <!--T:34--> |

| + | Head and neck markers are very visible, and may be used in species where the legs are not normally visible (such as ducks and geese). '''Nasal discs''' and '''nasal saddles''' can be attached to the culmen with a pin looped through the nostrils in birds with perforate nostrils. They should not be used if they obstruct breathing. They should not be used on birds that live in icy climates, as accumulation of ice on a nasal saddle can plug the nostrils. '''Neck collars''' made of expandable, non-heat-conducting plastic are very useful for larger birds such as geese. | ||

| − | + | ===Some results=== <!--T:35--> | |

| + | [[Image:LarusRidibundusFlight-01.jpg|thumb|250px|left|Ringed Larus ridibundus in flight]] | ||

| + | An Arctic Tern ringed as a chick not yet able to fly, on the Farne Islands off the Northumberland coast in eastern Britain in summer 1982, reached Melbourne, Australia in October 1982, a sea journey of '''over 22,000 km''' (14,000 miles) in just three months from fledging (developing the ability to fly). | ||

| − | + | <!--T:36--> | |

| + | A Manx Shearwater ringed as an adult (at least 5 years old), breeding on Copeland Island, Northern Ireland, is currently (2003/2004) the oldest known wild bird in the world: ringed in July 1953, it was retrapped in July 2003, at least '''55 years''' old. Other ringing recoveries have shown that Manx Shearwaters migrate over 10,000 km to waters off southern Brazil and Argentina in winter, so this bird has covered a ''minimum'' of 1,000,000 km on migration alone (not counting day-to-day fishing trips). Another bird nearly as old, breeding on Bardsey Island off Wales was calculated by ornithologist Chris Mead to have flown over 8 million km (5 million miles) during its life (and this bird was still alive in 2003, having outlived Chris Mead). | ||

| + | [[File:Manx_Shearwater.JPG|thumb|250px|left|Manx Shearwater]] | ||

| − | + | <!--T:82--> | |

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 6 --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=7}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:83--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | <!-- 7. Name the main migratory bird flyways used by birds in your continent. --> | ||

| + | [[Image:Waterfowlflywaysmap.png|right]] | ||

| + | The main migration routes in North America are known as the '''Atlantic''', '''Mississippi''', '''Central''', and '''Pacific'''. | ||

| + | {{clear}} | ||

| − | + | <!--T:84--> | |

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 7 --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=8}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:85--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

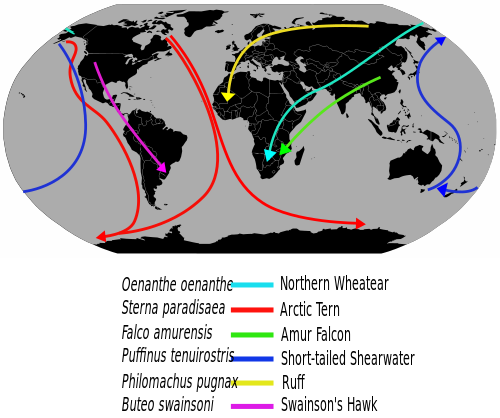

| + | <!-- 8. Give the migration routes and terminal destinations for ten different migratory bird species. --> | ||

| + | Both the routes and the terminal destinations can be found on the maps below. | ||

| − | + | <!--T:39--> | |

| − | + | <gallery widths="300px" heights="400px" perrow="2" Caption="Migration Routes of eight bird species" align=center> | |

| − | + | Image:Migration route western tanager.gif|Western Tanager | |

| − | + | Image:Migration route scarlet tanager.gif |Scarlet Tanager | |

| + | Image:Migration route ross goose.gif|Ross's Goose | ||

| + | Image:Migration route rose breasted grosbeak.gif|Rose-breasted Grosbeak | ||

| + | Image:Migration route harris sparrow.gif|Harris' Sparrow | ||

| + | Image:Migration route canvasback.gif|Canvasback | ||

| + | Image:Migration route bobolink.gif|Bobolink | ||

| + | Image:Migration route american redstart.gif|American Redstart | ||

| + | </gallery> | ||

| − | + | <!--T:40--> | |

| − | + | [[Image:Migrationroutes.svg|thumb|500px|center|Migration routes of six bird species]] | |

| + | {{clear}} | ||

| − | == | + | <!--T:86--> |

| − | + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | |

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 8 --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=9}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:87--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | <!-- 9. Describe at least three different ways that birds are able to orient themselves in their movements across the globe. --> | ||

| + | Navigation is based on a variety of senses. Many birds have been shown to use a '''sun compass'''. Using the sun for direction involves the need for making compensation based on the time. Navigation has also been shown to be based on a combination of other abilities including the ability to detect '''magnetic fields''', use '''visual landmarks''' as well as '''olfactory cues'''. | ||

| − | == | + | <!--T:88--> |

| − | + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | |

| − | + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 9 --> | |

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=10}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:89--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | <!-- 10. Make a list of 60 species of wild birds, including birds from at least ten different families, that you personally have observed and positively identified by sight out of doors. For each species on this list note the following: <br>a. Name <br>b. Date observed <br>c. Place observed <br>d. Habitat (i.e., field, woods, river, lake, etc.) <br>e. Status where observed (permanent resident, winter resident, summer resident, migrant, vagrant) --> | ||

| + | Birders equip themselves with a [http://amzn.to/1H68m1G good field guide] and a checklist of birds found in the the local area they are birding. While the field guide may cover the whole continent or country and include helpful pictures and data that help you fill in the info you need for this requirement, a local checklist will narrow down the birds you can expect to actually see. You can easily find bird checklists online - look for a birding club in your area or check out /http://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/avibase.jsp?lang=EN which is based in Canada but covers the world with various degrees of completeness. | ||

| − | + | <!--T:57--> | |

| − | + | The most active times of the year for birding in temperate zones are during the spring or fall migrations when the greatest variety of birds may be seen. On these occasions, large numbers of birds travel north or south to wintering or nesting locations. | |

| − | + | <!--T:43--> | |

| − | + | Early morning is typically the best time of the day for birding since many birds are searching for food which makes them easier to find and observe. | |

| − | + | <!--T:44--> | |

| + | Birders who are keen rarity-seekers will travel long distances to locate new and rare species, intending to add these to their list of personally observed birds. These lists often take the form of a life list, national list, state list, county list, or year list. | ||

| − | + | <!--T:45--> | |

| − | + | Seawatching is a type of birdwatching where observers based at a coastal watch point, such as a headland, watch birds flying over the sea. This is one form of pelagic birding, by which pelagic bird species are viewed. Another way birders view pelagic species is from seagoing vessels. | |

| − | <!-- | ||

| − | --> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <!--T:46--> | |

| − | + | Many birders take part in censuses of bird populations and migratory patterns which are sometimes specific to individual species. These birders may also count all birds in a given area, as in the Christmas Bird Count. This citizen science can assist in identifying environmental threats to the well-being of birds or, conversely, in assessing outcomes of environmental management initiatives intended to ensure the survival of at-risk species or encourage the breeding of species for aesthetic or ecological reasons. This more scientific side of the hobby is an aspect of ornithology, coordinated in the UK by the British Trust for Ornithology. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <!--T:47--> | |

| − | + | Increasing seasonal bird populations can be a good indication of biodiversity or the quality of different habitats. Some species are persecuted as vermin, often illegally, as with the case of the Hen Harrier in Britain. | |

| − | + | <!--T:90--> | |

| − | {{ | + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> |

| − | + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 10 --> | |

| − | + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=11}} | |

| − | + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:91--> | |

| − | + | </noinclude> | |

| + | <!-- 11. Present lists of birds, showing the greatest number of species seen out of doors in: <br>a. One day (with at least six hours in the field) <br>b. One week <br>c. Your lifetime (all birds observed by you since you began birding to date) --> | ||

| + | As you observe birds and record the data called for in requirement 10, you can go through the data at a later time to collect this information. You can also log your observations online at places such as http://www.birdingcentral.com/ Using the Internet for logging your data will connect you to an international community of bird watchers. You will be better able to know when and where to look for various species of birds, and you may make some lifelong friends in the process. | ||

| − | + | <!--T:92--> | |

| − | + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | |

| − | + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 11 --> | |

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=12}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:93--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | <!-- 12. Make a list of ten species of wild birds that you personally have positively identified by sound out of doors, and describe or imitate these bird sounds as best you can. --> | ||

| + | Birding often involves a significant auditory component, as many bird species are more readily detected and identified by ear than by eye. Listen to the bird calls found in the [https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Field_Guide/Birds|Wikibooks Field Guide]. Then listen for them in the wild. You can also check out [http://amzn.to/1H65vG6 Birding by Ear] guides. | ||

| − | {{ | + | <!--T:94--> |

| + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | ||

| + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 12 --> | ||

| + | {{ansreq|page={{#titleparts:{{PAGENAME}}|2|1}}|num=13}} | ||

| + | <noinclude><translate><!--T:95--> | ||

| + | </noinclude> | ||

| + | <!-- 13. Lead a group in a bird observation walk or tell two Bible stories in which a bird was significant. --> | ||

| + | You will learn where the best places to see birds are as you go out birding yourself. If possible, take a group to one of those places. You can combine this trip with one of another purpose (such as a hike). | ||

| − | + | <!--T:51--> | |

| − | + | Bible stories that feature a bird as a significant part include, Noah sending out the dove, and Elijah being fed by ravens. In the Sermon on the Mount Jesus asks us to consider the birds of the air (they neither sow nor reap). The baptism of Jesus and Pentecost also feature doves. | |

| − | {{ | + | <!--T:96--> |

| − | + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | |

| − | + | {{CloseReq}} <!-- 13 --> | |

| − | + | <noinclude><translate></noinclude> | |

| − | + | ==References== <!--T:52--> | |

| − | + | <noinclude></translate></noinclude> | |

| − | + | <references/> | |

| − | + | {{CloseHonorPage}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 22:00, 13 July 2022

1

For tips and instruction see Birds.

2

United States

In the United States, birds are protected by a fairly large number of international treaties and domestic laws. These can be categorized as primary and secondary authorities. Primary authorities are international conventions and major domestic laws that focus primarily on migratory birds and their habitats. Secondary authorities are broad-based domestic environmental laws that provide ancillary but significant benefits to migratory birds and their habitats.

United States Federal laws that protect bird populations

- The Lacey Act

- (passed on May 25, 1900) prohibited game taken illegally in one state to be shipped across state boundaries contrary to the laws of the state where taken.

- Weeks-McLean Law

- (which became effective on March 4, 1913) was designed to stop commercial market hunting and the illegal shipment of migratory birds from one state to another. The Act boldly proclaimed that:

- All wild geese, wild swans, brant, wild ducks, snipe, plover, woodcock, rail, wild pigeons, and all other migratory game and insectivorous birds which in their northern and southern migrations pass through or do not remain permanently the entire year within the borders of any State or Territory, shall hereafter be deemed to be within the custody and protection of the Government of the United States, and shall not be destroyed or taken contrary to regulations hereinafter provided therefor.

- Migratory Bird Treaty Act

- The Migratory Bird Treaty Act is the domestic law that affirms, or implements, the United States' commitment to four international conventions (with Canada, Japan, Mexico, and Russia) for the protection of a shared migratory bird resource. Each of the conventions protect selected species of birds that are common to both countries (i.e., they occur in both countries at some point during their annual life cycle).

- Endangered Species Act

- The Endangered Species Act is also the domestic law that confirms, or implements, the United States' commitment to two international treaties that contain important provisions for the protection of migratory birds:

- CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora)

- Pan American Convention (the Convention on Nature Protection and Wildlife Preservation in the Western Hemisphere).

- Other International Treaties

- In additional to the conventions implemented by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and the Endangered Species Act, the United States is party to two other international treaties that afford special protection to migratory birds.

- Ramsar Convention (The Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitats)

- Antarctic Treaty (designed to protect the native birds, mammals, and plants of the Antarctic)

- Other Domestic Laws

- Other domestic laws protecting birds in the United States include:

- Bald Eagle Protection Act

- Waterfowl Depredations Prevention Act

- Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act

- Wild Bird Conservation Act

United States Federal Laws protecting bird habitats

- Duck Stamp Act

- The Duck Stamp Act provides a mechanism for generating money for the acquisition and protection of important migratory bird habitats.

- Wetlands Loan Act

- The Wetlands Loan Act, approved October 4, 1961, authorized an advance of funds against future revenues from sale of "duck stamps" as a means of accelerating the acquisition of migratory waterfowl habitat.

- Emergency Wetlands Resources Act

- The Emergency Wetlands Resources Act, approved November 10, 1986, authorized the purchase of wetlands from Land and Water Conservation Fund monies, removing a prior prohibition on such acquisitions.

- Migratory Bird Conservation Act

- The Migratory Bird Conservation Commission was established on February 18, 1929 by the passage of the Migratory Bird Conservation Act. It was created and authorized to consider and approve any areas of land and/or water recommended by the Secretary of the Interior for purchase or rental by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service under the Act, and to fix the price or prices at which such areas may be purchased or rented. In addition to approving purchase and rental prices, the Commission considers the establishment of new waterfowl refuges.

- North American Wetlands Conservation Act

- The North American Wetlands Conservation Act does several things:

- It encourages partnerships to conserve North American wetland ecosystems for waterfowl, other migratory birds, fish, and wildlife.

- It encourages the formation of public-private partnerships to develop and implement wetland conservation projects consistent with the North American Waterfowl Management Plan (NAWMP), a blueprint for continental waterfowl and wetlands conservation, and other North American migratory bird conservation agreements.

- It creates the North American Wetlands Conservation Fund to help support projects through grants.

- It establishes a nine-member North American Wetlands Conservation Council (Council) to review and recommend grant proposals to the Migratory Bird Conservation Commission for funding.

Canada

Most species of birds in Canada are protected under the Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994 (MBCA). The MBCA was passed in 1917, and updated in 1994 and 2005, to implement the Migratory Birds Convention, a treaty signed with the United States in 1916. As a result, the Canadian federal government has the authority to pass and enforce regulations [Migratory Birds Regulations (C.R.C., c. 1035)] to protect those species of birds that are included in the Convention. Similar legislation in the United States [Birds Protected By The Migratory Bird Treaty Act] protects birds species found in that country, though the list of bird species protected by each country can be different.&

Each Province and Territory protects a list of bird through legislation usually called the Wildlife Act (or similar)

3

4

4a

Bird feet have many specializations. For example, perching birds have a tendon locking mechanism in their feet that helps them hold on to the perch when they are asleep. Aquatic birds have webbed feet used for efficient propulsion through the water. Birds of prey have sharp talons on the ends of their feet which they use for capturing and killing their prey. The male emperor penguin's feet are specially shaped so that he can hold an egg on top of them as he covers it with his body to keep it warm. The ostrich has just two toes on each foot (most birds have four), with the nail of the larger, inner one resembling a hoof. The outer toe lacks a nail. This is an adaptation unique to Ostriches that appears to aid in running.

Their legs are also specialized. Wading birds have long legs to allow them to venture into deeper water in search of fish. The ostrich has large, powerful legs for running (they can reach speeds of 65 km/h (40 mph), the top land speed of any bird. Furthermore, their legs are featherless, which allows them to control their temperature. When it's cold, they can cover their thighs with their wings. When it's hot, they uncover them, allowing them to cool off.

Their beaks are highly specialized as well, adapted for eating insects, grain, coniferous-seeds, nectar, or fruit. They are also adapted to various forms of hunting, including dip netting, surface skimming, mud probing, filter feeding, fishing, or scavenging.

4b

i

Hummingbirds are attracted to many flowering plants. They feed on the nectar of these plants and are important pollinators, especially of deep-throated flowers.

They also typically consume more than their own weight in nectar each day, and to do so they must visit hundreds of flowers daily. At any given moment, they are only hours away from starving.

Hummingbirds feed in many small meals, consuming up to their own body weight in nectar and insects per day. They spend an average 10%-15% of their time feeding and 75%-80% sitting, digesting and watching. Obtaining this much food requires a lot of work. Scientists have recorded a Costa's Hummingbirds making 42 feeding flights in 6-5 hours, during which time it visited 1,311 flowers.

ii

Hummingbirds are such skillful fliers that they have no fear of predators. They can usually elude them with ease.

iii

Most birds move their wings up and down when they fly, but a hummingbird moves its wings front-to-back in a figure-eight pattern. This allows them to generate lift on both the forward and backward strokes, as well as endowing them with the ability to hover and fly backwards.

iv

Ruby-throated Hummingbirds migrate across the Gulf of Mexico, averaging 40 km/h (25 mph).

v

Hummingbirds are known for their ability to hover in mid-air by rapidly flapping their wings 15–80 times per second (depending on the species). Their heart rate can reach as high as 1,260 beats per minute, a rate once measured in a Blue-throated Hummingbird. However, they are capable of slowing down their metabolism at night, or any other time food is not readily available, entering a hibernation-like state known as torpor. During torpor, the heart rate and rate of breathing are both slowed dramatically (the heart rate to roughly 50–180 beats per minute), reducing their need for food.

vi

Hummingbirds' tongues are bifurcated - a fancy way of saying that like a snake, the hummingbird has a forked tongue.

5

- Primaries

- Secondaries

- Coverts

- Axillars

- Alulae

- The alulea (singular is alula) are small projections on the leading edge of the wing near the carpal joint (6). They are actually one of the bird's digits, and are typically covered with three to five small feathers, with the exact number depending on the species. Like the larger flight feathers found on the wing's trailing edge, these alula feathers are asymmetrical, with the shaft running closer to leading edge.

6

Bird banding (also known as bird ringing) is an aid to studying wild birds, by attaching a small individually numbered metal or plastic ring to their legs or wings, so that various aspects of the bird's life can be studied by the ability to re-find the same individual later. This can include migration, longevity, mortality, population studies, feeding behavior, and many other aspects.

Terminology and techniques

Those who ring birds are called "bird ringers". Organized banding efforts are called "ringing schemes" and the organizations that run them, "ringing authorities". Birds are "ringed" (rather than "rung"). When a ringed bird is found, and the ring number read and reported back to the ringer or ringing authority, this is termed a "ringing recovery" or "control".

Birds are either ringed at the nest, or after being trapped in fine mist nets, Heligoland traps, drag nets, cannon nets, duck decoys or similar.

A ring of suitable size is attached, and has on it a unique number, plus a contact address. The bird is often weighed and measured, and examined for parasites (which may then be removed) before release. The rings are very light-weight, and have no adverse effect on the birds. The individual birds can then be identified when they are re-trapped, or found dead.

The finder can contact the address on the ring, give the unique number, and be told the known history of the bird's movements.

The organizing body, by collating many such reports, can then determine patterns of bird movements for large populations.

The first organized schemes for bird ringing were started (in 1909) by Arthur Landsborough Thomson in Aberdeen and Harry Witherby in England, though smaller individual marking tests had began some years earlier in Denmark and Germany.

Similar schemes

Wing tags

In some surveys, involving larger birds such as eagles, brightly-colored plastic tags are attached to birds' wing feathers. Each has a letter or letters, and the combination of color and letters uniquely identifies the bird. These can then be read in the field, through binoculars, meaning that there is no need to re-trap the birds. Because the tags are attached to feathers, they drop off when the bird moults. Imping is the practice of replacing a bird's normal feather with a brightly-colored false feather. A patagial tag is a permanent tag held onto the wing by a rivet punched through the patagium.

Radio transmitters and satellite-tracking

Where detailed information is needed on an individuals' movements, scientists can fit tiny radio transmitters to birds. For small species the transmitter is carried as a 'backpack' fitted over the wing bases, and for larger species it may be attached to a tail feather or temporary leg band. Both types usually have a tiny (10cm) flexible aerial to improve signal reception. Two field receivers (reading distance and direction) are needed to establish the bird's position using triangulation. Transmitters may be recovered by recapturing the bird or designed to drop off. The technique is useful for tracing individuals during landscape-level movements particularly in dense vegetation (such as tropical forests) and for shy or difficult-to-spot species, because birds can be located from a distance without visual confirmation. The use of satellite transmitters for bird movements is currently restricted by transmitter size - to species larger than about 400g. They may be attached to migratory birds (geese and swans are popular subjects) or other species undergoing longer-distance flights. Individuals may be tracked by satellites for immense distances, for the lifetime of the transmitter battery. As with wing tags, the transmitters may be designed to drop off when the bird moults; or they may be recovered by recapturing the bird.

Field-readable rings

A field-readable is a ring or rings, usually made from plastic and brightly colored, which may also have conspicuous markings in the form of letters and/or numbers. They are used by biologists working in the field to identify individual birds without recapture and with a minimum of disturbance to their behavior. Rings large enough to carry numbers are usually restricted to larger birds, although if necessary small extensions to the rings (leg flags) bearing the identification code allow their use on slightly smaller species. For small species (e.g. most passerines), individuals can be identified by using a combination of small rings of different colors, which are read in a specific order. Most color-marks of this type are considered temporary (the rings degrade, fade and may be lost or removed by the birds) and individuals are usually also fitted with a permanent metal ring.

Other markers

Head and neck markers are very visible, and may be used in species where the legs are not normally visible (such as ducks and geese). Nasal discs and nasal saddles can be attached to the culmen with a pin looped through the nostrils in birds with perforate nostrils. They should not be used if they obstruct breathing. They should not be used on birds that live in icy climates, as accumulation of ice on a nasal saddle can plug the nostrils. Neck collars made of expandable, non-heat-conducting plastic are very useful for larger birds such as geese.

Some results

An Arctic Tern ringed as a chick not yet able to fly, on the Farne Islands off the Northumberland coast in eastern Britain in summer 1982, reached Melbourne, Australia in October 1982, a sea journey of over 22,000 km (14,000 miles) in just three months from fledging (developing the ability to fly).

A Manx Shearwater ringed as an adult (at least 5 years old), breeding on Copeland Island, Northern Ireland, is currently (2003/2004) the oldest known wild bird in the world: ringed in July 1953, it was retrapped in July 2003, at least 55 years old. Other ringing recoveries have shown that Manx Shearwaters migrate over 10,000 km to waters off southern Brazil and Argentina in winter, so this bird has covered a minimum of 1,000,000 km on migration alone (not counting day-to-day fishing trips). Another bird nearly as old, breeding on Bardsey Island off Wales was calculated by ornithologist Chris Mead to have flown over 8 million km (5 million miles) during its life (and this bird was still alive in 2003, having outlived Chris Mead).

7

The main migration routes in North America are known as the Atlantic, Mississippi, Central, and Pacific.

8

Both the routes and the terminal destinations can be found on the maps below.

- Migration Routes of eight bird species

9

Navigation is based on a variety of senses. Many birds have been shown to use a sun compass. Using the sun for direction involves the need for making compensation based on the time. Navigation has also been shown to be based on a combination of other abilities including the ability to detect magnetic fields, use visual landmarks as well as olfactory cues.

10

- a. Name

- b. Date observed

- c. Place observed

- d. Habitat (i.e., field, woods, river, lake, etc.)

- e. Status where observed (permanent resident, winter resident, summer resident, migrant, vagrant)

Birders equip themselves with a good field guide and a checklist of birds found in the the local area they are birding. While the field guide may cover the whole continent or country and include helpful pictures and data that help you fill in the info you need for this requirement, a local checklist will narrow down the birds you can expect to actually see. You can easily find bird checklists online - look for a birding club in your area or check out /http://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/avibase.jsp?lang=EN which is based in Canada but covers the world with various degrees of completeness.

The most active times of the year for birding in temperate zones are during the spring or fall migrations when the greatest variety of birds may be seen. On these occasions, large numbers of birds travel north or south to wintering or nesting locations.

Early morning is typically the best time of the day for birding since many birds are searching for food which makes them easier to find and observe.

Birders who are keen rarity-seekers will travel long distances to locate new and rare species, intending to add these to their list of personally observed birds. These lists often take the form of a life list, national list, state list, county list, or year list.

Seawatching is a type of birdwatching where observers based at a coastal watch point, such as a headland, watch birds flying over the sea. This is one form of pelagic birding, by which pelagic bird species are viewed. Another way birders view pelagic species is from seagoing vessels.

Many birders take part in censuses of bird populations and migratory patterns which are sometimes specific to individual species. These birders may also count all birds in a given area, as in the Christmas Bird Count. This citizen science can assist in identifying environmental threats to the well-being of birds or, conversely, in assessing outcomes of environmental management initiatives intended to ensure the survival of at-risk species or encourage the breeding of species for aesthetic or ecological reasons. This more scientific side of the hobby is an aspect of ornithology, coordinated in the UK by the British Trust for Ornithology.

Increasing seasonal bird populations can be a good indication of biodiversity or the quality of different habitats. Some species are persecuted as vermin, often illegally, as with the case of the Hen Harrier in Britain.

11

- a. One day (with at least six hours in the field)

- b. One week

- c. Your lifetime (all birds observed by you since you began birding to date)

As you observe birds and record the data called for in requirement 10, you can go through the data at a later time to collect this information. You can also log your observations online at places such as http://www.birdingcentral.com/ Using the Internet for logging your data will connect you to an international community of bird watchers. You will be better able to know when and where to look for various species of birds, and you may make some lifelong friends in the process.

12

Birding often involves a significant auditory component, as many bird species are more readily detected and identified by ear than by eye. Listen to the bird calls found in the Field Guide. Then listen for them in the wild. You can also check out Birding by Ear guides.

13

You will learn where the best places to see birds are as you go out birding yourself. If possible, take a group to one of those places. You can combine this trip with one of another purpose (such as a hike).

Bible stories that feature a bird as a significant part include, Noah sending out the dove, and Elijah being fed by ravens. In the Sermon on the Mount Jesus asks us to consider the birds of the air (they neither sow nor reap). The baptism of Jesus and Pentecost also feature doves.