AY Honors/African Lore/Answer Key

1

The answers for requirement two include information about the location of the tribes described. We suggest that you consult a map of Africa and using the information presented below, locate the areas where ten tribes are today. Requirement two also provides many outstanding features of the tribes described.

2

2a

There are thousands of tribes in Africa, and we will not pretend to describe them all. Rather, we will present a small handful of the largest tribes here, and even then, not with much detail. If an African tribe not described here interests you, you are encouraged to research it. If you like, you can add your research to this Wikibook.

2b

(1) Eating habits

(2) Initiation ceremony

(3) Witch doctors

(4) Living and worship conditions

(5) Education

(6) Burials

(7) Money

(8) Dress

(9) Industry

Acholi

| Acholi |

|---|

|

Living conditions: Their traditional dwelling-places were circular huts with a high peak, furnished with a mud sleeping-platform, jars of grain and a sunk fireplace, with the walls daubed with mud and decorated with geometrical or conventional designs in red, white or grey. Burial: When a man dies he is buried near the entrance of his hut. The grave is left open and guarded by a young person until it begins to decompose. At that time, it is considered safe to bury the corpse. After burial, a fence is erected around the grave, and trees are planted on top of it. The Acholi consider it unfortunate for a man to die of natural causes. It is considered lucky for a man to die while hunting or while fighting a war, even though the body is left unburied in these cases, left for the vultures.

Location: Southern Sudan, Northern Uganda |

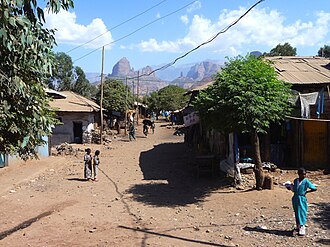

Amhara

| Amhara |

|---|

|

Eating habits: Barley, corn, millet, wheat, sorghum, and teff, along with beans, peppers, chickpeas, and other vegetables, are the most important crops. In the highlands one crop per year is normal, while in the lowlands two are possible. Cattle, sheep, and goats are also raised. File:Birr.JPG Ethopian birr The birr is the unit of currency in Ethiopia. Before 1976, dollar was the official English translation of birr. Today, it is officially birr in English as well. |

Fula

| Fula |

|---|

|

Eating habits: Dairy is an important part of the diet, including milk, yogurt, and butter. Their main meal of the day will feature a porridge made from grain (millet, sorghum, or corn). Dress: The traditional dress of the Fula in most places consists of long colorful flowing robes, modestly embroidered or otherwise decorated. |

Igbo

| Igbo |

|---|

|

Eating habits: The yam is very important to the Igbo as it is their staple crop. There are celebrations such as the New yam festival which are held for the harvesting of the yam. During the festival yam is eaten throughout the communities as celebration. Yam tubers are shown off by individuals as a sign of success and wealth. Rice has replaced yam for ceremonial occasions. Other foods include cassava, garri, maize and plantains. Soups or stews are included in a typical meal, prepared with a vegetable (such as okra, of which the word derives from the Igbo language, Okwuru) to which pieces of fish, chicken, beef, or goat meat are added. Jollof rice is popular throughout West Africa. The Igbo believe in reincarnation. People are believed to reincarnate into families that they were part of while alive. Before a relative dies, it is said that the soon to be deceased relative sometimes give clues of who they will reincarnate as in the family. Once a child is born, he or she is believed to give signs of who they have reincarnated from. This can be through behavior, physical traits and statements by the child. A diviner can help in detecting who the child has reincarnated from. Different types of deaths warrant different types of burials. This is affected by an individual's age, gender and status in society. For example, children are buried in hiding and out of sight, their burials usually take place in the early mornings and late nights. A simple untitled man is buried in front of his house and a simple mother is buried in her place of origin in a garden or a farm-area that belonged to her father. Presently, a majority of the Igbo bury their dead in the western way, although it is not uncommon for burials to be practiced in the traditional Igbo ways. File:Stamp Nigeria 1953 0.5p manilla.jpg A Stamp depicting Manillas Manillas are ring-like armlets, mostly in bronze or copper, very rarely gold, which served as a form of money or barter coinage and to a degree, ornamentation, amongst certain West African peoples including the Igbo. They also became known as "slave trade money" after the Europeans started using them to acquire slaves for the slave trade into the Americas (as well as England prior to 1807). Women traditionally carry their babies on their backs with a strip of clothing binding the two with a knot at her chest, a practice used by many ethnic groups across Africa. This method has been modernized in the form of the child carrier. In most cases Igbo women did not cover their breast areas. Maidens usually wore a short wrapper with beads around their waist and other ornaments such as necklaces and beads. Both men and women wore wrappers. Men would wear loin cloths that wrapped round their waist and between their legs to be fastened at their back, the type of clothing appropriate for the intense heat as well as jobs such as farming. In the same era as the rise of colonial forces in Nigeria, the way the Igbo dressed changed. These changes made the Igbo adopt Westernized clothing such as shirts and trousers. Clothing worn before colonialism became "traditional" and worn on special occasions. The traditional clothing itself became westernized with the introduction of various types of Western clothing including shoes, hats, trousers, etc. Modern Igbo traditional attire, for men, is generally made up of the Isiagu top which resembles the Dashiki worn by other African groups. Isiagu (or Ishi agu) is usually patterned with lions heads embroidered over the clothing and can be a plain color. It is worn with trousers and can be worn with either a traditional title holders hat or with the traditional Igbo stripped men's hat. For women, a puffed sleeve blouse (influenced by European attire) along with two wrappers and a head tie are worn. |

Ijaw

| Ijaw |

|---|

|

Eating habits: Like many ethnic groups in Nigeria, the Ijaws have many local foods that are not widespread in Nigeria. Many of these foods involve fish and other seafoods such as clams, oysters and periwinkles; yams and plantains. Some of these foods are:

Initiation ceremony: Among the Okrika tribe of the Ijaw people, when a girl is about 17 years old, she (and the other girls in her community) undergoes a ritual called the Iria, which is a coming-of-age ceremony. This ceremony has elements common to many other initiation ceremonies, including isolation, instruction, transition, and celebration. In former times, a girl was expected to marry immediately following her Iria, but now it is acceptable for a woman to finish her education (including college) before marriage. The Iria still serves as an indication that a woman is eligible for marriage. Ijaw religious beliefs hold that water spirits are like humans in having personal strengths and shortcomings, and that humans dwell among the water spirits before being born. The role of prayer in the traditional Ijaw system of belief is to maintain the living in the good graces of the water spirits among whom they dwelt before being born into this world, and each year the Ijaw hold celebrations in honor the spirits lasting for several days. Central to the festivities is the role of masquerades, in which men wearing elaborate outfits and carved masks dance to the beat of drums and manifest the influence of the water spirits through the quality and intensity of their dancing. Particularly spectacular masqueraders are taken to actually be in the possession of the spirits on whose behalf they are dancing. |

Maasai

| Maasai |

|---|

|

Eating habits: Traditionally, the Maasai diet consisted of meat, milk, and blood from cattle. An ILCA study (Nestel 1989) states: “Today, the staple diet of the Maasai consists of cow's milk and maize-meal. The former is largely drunk fresh or in sweet tea and the latter is used to make a liquid or solid porridge. The solid porridge is known as uoali and is eaten with milk; unlike the liquid porridge, uoali is not prepared with milk. Meat, although an important food, is consumed irregularly and cannot be classified as a staple food. Animal fats or butter are used in cooking, primarily of porridge, maize, and beans. Butter is also an important infant food. Blood is rarely drunk.” During this period, the newly circumcised young men will live in a "manyatta", a "village" built by their mothers. The manyatta has no encircling barricade for protection, emphasizing the warrior role of protecting the community. No inner krall is built, since warriors neither own cattle or undertake stock duties. Further rites of passage are required before achieving the status of senior warrior, culminating in the eunoto ceremony, the "coming of age". Shúkà is the Maa word for sheets traditionally worn wrapped around the body, one over each shoulder, then a third over the top of them. These are typically red, though with some other colors (e.g. blue) and patterns (e.g. plaid.) Pink, even with flowers, is not shunned by warriors. One piece garments known as kanga, a Swahilli term, are common. Maasai near the coast may wear kikoi, a type of sarong that comes in many different colors and textiles. However, the preferred style is stripes. |

Oromo

Shona

| Shona |

|---|

|

Eating habits: The majority of Zimbabweans depend on a few staple foods. Meat, beef and to a lesser extent chicken are especially popular, though consumption has declined under the Mugabe regime due to falling incomes. "Mealie meal" (cornmeal) is used to prepare sadza or isitshwala and bota or ilambazi. Sadza is a porridge made by mixing the cornmeal with water to produce a thick paste. After the paste has been cooking for several minutes, more cornmeal is added to thicken the paste. This is eaten as lunch and dinner, usually with greens (such as spinach, chomolia, collard greens), beans and meat that has been stewed, grilled, or roasted. Sadza is also commonly eaten with curdled milk, commonly known as lacto (mukaka wakakora), or dried Tanganyika sardine, known locally as kapenta or matemba. Bota is a thinner porridge, cooked without the additional cornmeal and usually flavoured with peanut butter, milk, butter, or, sometimes, jam. Bota is usually eaten for breakfast. The wealthier portion of the population usually send their children to independent schools as opposed to the government-run schools which are attended by the majority as these are subsidised by the government. School education was made free in 1980, but since 1988, the government has steadily increased the charges attached to school enrollment until they now greatly exceed the real value of fees in 1980. The Ministry of Education of Zimbabwe maintains and operates the government schools but the fees charged by independent schools are regulated by the cabinet of Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe's education system consists of 7 years of primary and 6 years of secondary schooling before students can enter university in the country or abroad. The academic year in Zimbabwe runs from January to December, with three month terms, broken up by one month holidays, with a total of 40 weeks of school per year. National examinations are written during the third term in November, with "O" level and "A" level subjects also offered in June. If a person initiates the burial of a person of a different totem, he runs the risk of being asked to pay a fine to the family of the deceased. Such fines traditionally were paid with cattle or goats but nowadays substantial amounts of money can be asked for. Inflation rose from an annual rate of 32% in 1998 to an IMF estimate of 150,000% in December 2007, and to an official estimated high of 231,000,000% in July 2008 according to the country's Central Statistical Office. This represented a state of hyperinflation, and the central bank introduced a new 100 billion dollar note. As of November 2008, unofficial figures put Zimbabwe's annual inflation rate at 516 quintillion per cent, with prices doubling every 1.3 days. Zimbabwe's inflation crisis is now (2009) the second worst inflation spike in history, behind the hyperinflationary crisis of Hungary in 1946, in which prices doubled every 15.6 hours. By 2005, the purchasing power of the average Zimbabwean had dropped to the same levels in real terms as 1953. Local residents have largely resorted to buying essentials from neighbouring Botswana, South Africa and Zambia. |

Tuareg

| Tuareg |

|---|

|

Eating habits: The Tuareg diet consists mostly of grains supplemented with fruits such as dates and melons (when in season), and milk and cheese. Meat is reserved for special occasions.

Religion: The Tuareg are predominantly Muslim and generally follow the Maliki madhhab, one of the four schools of Fiqh or religious law within Sunni Islam. |

Xhosa

| Xhosa |

|---|

|

Eating habits: The Xhosa settled on mountain slopes of the Amatola and the Winterberg Mountains. Many streams drain into great rivers of this Xhosa territory including the Kei and Fish Rivers. Rich soils and plentiful rainfall make the river basins good for farming and grazing making cattle important and the basis of wealth. Traditional foods include beef (Inyama yenkomo), mutton (Inyama yegusha), and goat meat, sorghum, maize and dry maize porridge (umphokoqo), "umngqusho" (made from dried, stamped corn and dried beans), milk (often fermented, called amasi), pumpkins (amathanga), beans (iimbotyi), and vegetables. The Xhosas have a strong oral tradition with many stories of ancestral heroes; according to tradition, the leader from whose name the Xhosa people take their name was the first human on Earth. Other traditions have it that all Xhosas are descended from one ancestor named Tshawe. The key figure in the Xhosa oral tradition is the imbongi (plural: iimbongi) or praise singer. Iimbongi traditionally live close to the chief's "great place" (the cultural and political focus of his activity); they accompany the chief on important occasions - the imbongi Zolani Mkiva preceded Nelson Mandela at his Presidential inauguration in 1994. Iimbongis' poetry, called imibongo, praises the actions and adventures of chiefs and ancestors. Christian missionaries established outposts among the Xhosa in the 1820s, and the first Bible translation was in the mid-1850s, partially done by Henry Hare Dugmore. Xhosa did not convert in great numbers until the 1900s, but now many are Christian, particularly within the African Initiated Churches such as the Zion Christian Church. Some denominations combine Christianity with traditional beliefs. |

Yoruba

| Yoruba |

|---|

|

The popularly known Vodou religion of Haiti combines the religious beliefs of the many different African ethnic nationalities taken to the island with the structure and liturgy from the Fon-Ewe of present-day Benin and the Congo-Angolan culture area, but Yoruba-derived religious ideology and deities also play an important role. Yoruba deities include "Ọya" (wind/storm), "Ifá" (divination or fate), "Ẹlẹda" (destiny), Orisha or Orisa "Ibeji" (twin), "Ọsanyin" (medicines and healing) and "Ọsun" (goddess of fertility, protector of children and mothers), Sango (God of thunder). Human beings and other sentient creatures are also assumed to have their own individual deity of destiny, called "Ori", who is venerated through a sculpture symbolically decorated with cowrie shells. Traditionally, dead parents and other ancestors are also believed to possess powers of protection over their descendants. This belief is expressed in veneration and sacrifice on the grave or symbol of the ancestor, or as a community in the observance of the Egungun festival where the ancestors are represented as a colorful masquerade of costumed and masked men who represent the ancestral spirits. Dead parents and ancestors are also commonly venerated by pouring libations to the earth and the breaking of kolanuts in their honor at special occasions. Today, many contemporary Yoruba are active Christians (60%) and Muslims (30%), yet retain many of the moral and cultural concepts of their traditional faith.

Location: Nigeria, Benin, and Togo |

Zulu

| Zulu |

|---|

|

Eating habits: In the precolonial period, indigenous cuisine was characterized by the use of a very wide range of fruits, nuts, bulbs, leaves and other products gathered from wild plants and by the hunting of wild game. The domestication of cattle in the region about two thousand years ago by Khoisan groups enabled the use of milk products and the availability of fresh meat on demand. However, during the colonial period the seizure of communal land in South Africa restricted and discouraged traditional agriculture and wild harvesting, and reduced the extent of land available to black people. The initiation ceremony for girls began as soon as she began menstruation. She would gather the roots of a certain shrub and use it to make a porridge which she would eat exclusively for seven days. During this time, and for the enxt three months or so, she was confined to her mother's hut. During this time she was to learn to perform several tasks expected of women, including basket weaving and making beaded clothing. She was allowed to have one friend come and stay with her during this time. She was not allowed to be seen by anyone other than her mother and this friend. Her sisters would make her a new outfit from twisted grass, and at the end of the three months, she would put this on, be presented to the village, and she and her friend and sisters would dance and sing, celebrating the end of her initiation. On the following day, the grass outfit would be burned, signifying that the girl had become a woman. Although the word sangoma is generally used in South African English to mean all types of traditional Southern African healers, inyangas and sangomas are in fact different. An inyanga is an herbalist who is concerned with medicines made from plants and animals, while a sangoma relies primarily on divination for healing purposes. The knowledge of the inyanga is passed through the generations from parent to child. In modern society the status of these medicine men or women has been translated into wealth. Most izinyanga (plural of inyanga) in urban areas have shops with consulting rooms where they sell their medicines. Zulu religion includes belief in a creator God (Nkulunkulu) who is above interacting in day-to-day human affairs, although this belief appears to have originated from efforts by early Christian missionaries to frame the idea of the Christian God in Zulu terms. Traditionally, the more strongly held Zulu belief was in ancestor spirits (Amatongo or Amadhlozi), who had the power to intervene in people's lives, for good or ill. This belief continues to be widespread among the modern Zulu population. |

3

Hopefully you can find and tell a folk story for the tribe you studied, but here is an example.

How the Monkeys Saved the Fish

This is a traditional Tanzanian folktale.

- Story

- It was the rainy season, and the river had flooded its banks. The animals were all fleeing for their lives as the river rushed down and carried everything away. Many animals died in the flood, but not the monkeys. Because of their great agility, the monkeys were able to climb the trees and escape the flood waters. As they sat in the trees, they noticed the fish swimming in the current.

- The monkeys were very concerned about the fish, saying "Unless we do something, these fish are going to drown!" So the monkeys decided to make their way to the edge of the river where the water was not so deep. "From there, we will be able to save these legless creatures." The monkeys set about their task, grabbing the fish from the river and heaping them in a great pile. When they were finished they saw that the fish were all motionless. "The fish are sleeping now because they are so tired. They struggled against us because they did not know our good intentions." they said to one another. "When they awake, they will be so happy that we saved them."

- Moral

- Before you can help someone, you must understand their situation.

4

Unless you live in Africa or are able to visit there, this requirement may end up costing a substantial amount of money. It may also take a prolonged amount of time to complete your collection. If you would like to shop for African objects online, we recommend that you apply the following terms to an Internet search engine:

- Africa+gifts

- Africa+crafts

- Africa+imports

- African+artisans

If you live in a large city (or near one), you may be able to find a local shop specializing in African imports. You could also check for a museum of African history and check their gift shop. If you know some immigrants from Africa, you may be able to trade with them.