AY Honor Heraldry - Advanced Answer Key

1

For tips and instruction see Heraldry.

2

It is thought that troubadours (strolling minstrels) formed the first body of messengers for the monarch. They couriered small items, relayed orders and ‘heralded’ the king’s arrival.

Landowners too had a use for them. Land acquired by marriage or by grant of the monarch could be scattered about the country and the services of these travelling messengers – soon to be called ‘heralds’ – was essential.

As they became known to one another, the heralds amassed an encyclopaedic knowledge of their masters’ signs and devices. With duplication almost inevitable, it was in everyone’s interest to achieve unique identification and, initially at an informal local level, the heralds’ persuasion brought about changes and an attempt at regulation.

Their knowledge of the craft was respected, sought after – and eventually termed ‘heraldry’.

3

Impetus was given to the development of heraldry by the 12th century Crusades, particularly the Third Crusade in 1189, by which time heraldry had ‘broken out all over Europe’.

The earliest shields had been simple affairs in one or two colours and, later, sported geometric shapes in a contrasting colour. These were followed by the arrival of the graphical image – animate and inanimate objects in all their potential varieties.

This caused the Heralds to struggle to maintain even a semblance of order.

In 1484, Richard III founded the College of Arms, and they were incorporated by Royal charter.

In the following century, with a set of ground rules formulated and disputes to be settled, they began the Visitations: a series of tours in which they visited families to record their arms or grant new ones.

The granting of arms has been the prerogative of the Heralds ever since, now ably represented by Her Majesty’s College of Arms in London, the Court of Lord Lyon in Edinburgh, and the Office of the Chief Herald of Ireland in Dublin.

4

Whether we are aware of it or not, heraldry has woven itself into the tapestry of our lives.

It is all around us and constantly growing with the grants of arms being issued on an almost daily basis.

Families, civic authorities, the law, the armed services, the church: all have seized upon – and continue to grasp – this powerful tool of identity. It features on their letterheads and in their pageantry.

People, places and corporate bodies still seek to identify themselves uniquely, whether by the display of a registered heraldic shield and motto, or a simple trademarked logo and catchphrase. History demonstrates that it has been heraldry which endures.

5

Although the essential and most important element, the shield is but one part of a coat of arms. While the traditional shield shape is for men, the Diamond or Lozenge shape is for women and the Oval design is for the clergy.

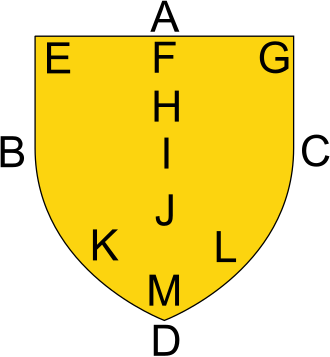

The surface of the shield (or escutcheon) is the field. This is divided into chief and base (top and bottom), sinister and dexter (left and right), are described from the viewpoint of the bearer standing behind the shield. Combinations of these terms, together with pale (the centre vertical third) and fess (the centre horizontal third), create a grid of nine points to locate the charges, or designs, placed upon the shield.

A - Chief

B - Dexter

C - Sinister

D - Base

E - Dexter Chief

F - Middle Chief

G - Sinister Chief

H - Honour Point

I - Fess Point

J - Nombril Point

K - Dexter Base

L - Sinister Base

M - Middle Base (seldom used)

The centre of the pale in chief is the honour point, the centre of the pale in base is the nombril point, and the exact centre of the shield is the fess point.

Also, the field can be divided in a number of ways so that different tinctures (colours), and furs (patterns) can appear on them. These are known as charge patterns.

A full Achievement of Arms can (but not always will) consist of supporters, mantling, a compartment, a motto, a helmet, a wreath, a crest, a badge, a banner, a flag – and more.

6

The Divisions of the Field, the Ordinaries and the Sub-Ordinaries can have their edges described by a simple straight line or a repetitive ornamental pattern.

7

7a

The blazon – the written description of the arms – can use a combination of English, Norman French and Latin, often with poor punctuation and abbreviations. The description begins at top left, proceeds to the right and then, moving downwards, passes from left to right.

Originally the passport or DNA record of its time, there was no room for ambiguity, since it was used not only to pinpoint identity but also for faithful reproduction.

7b

Often on the Shield symbolic lines, or Ordinaries can be found. A broad band across the top is known as a Chief and stands for domination of will. A Pale is a vertical band down the shield and shows great defensive military strength. A Cross would denote the Christian faith of the bearer.

7c

A mound on which the Supporters of the shield can stand, it is usually consistent with the arms’ design – frequently a grassy knoll, but also a pebbly beach, sea waves or brickwork.

7d

Mottoes, probably deriving from war cries, express pious hopes or sentiments and usually appear on a scroll beneath both the shield and any decorations, orders and medals hanging from it.

They can use any language (often Latin) and, since they are not included in the descriptive blazon. Also, their tinctures can be independent of the arms.

7e

Supporters are found on either side of the shield and are standing erect on the compartment and holding or guarding the shield. They usually have some local relevance or they are hereditary. Examples include real or imaginary animals, human figures, or even a plant.

7f

Originally attached to the helm, a mantle or small cloak hung down the back probably as protection from the sun. It is now a decorative accessory displayed each side of the crest and shield and, like the torse, reflects the tinctures of the arms: the principal colour on the outside and the principal metal on the lining.

7g

Covering the join between the crest and the helm, the torse or wreath is a twisted strand of six folds, possibly originating as a lady’s favour (love token). It alternates the two principal tinctures (metal and colour) in the arms, the first fold on the dexter side (the viewer’s left) being of the arms’ metal tincture.

7h

Helmet (‘helm’) designs varied with the period. The position of the helm and the visor is also an indicator of rank of the arms’ owner. The owner’s rank governs both the type of helm and the direction it faces.

7i

Standing upon the torse, and above the helm is the crest. Their primary purpose was to aid the identification of a knight in battle. For that reason, neither women nor clergy are supposed to bear crests.

Examples include animals, arms holding weapons, or bird's wings.

7j

A form of – or in place of – the crest. Peers’ coronets reflect their position: Duke, Marquess, Earl, Viscount and Baron. Similarly, crowns can reflect the arms’ owner’s work: Mural (soldiers), Naval (sailors), Astral (airmen).

8

The numerous combinations of shapes, patterns, sculpted edges, and tinctures were impressive, but they fell far short of a truly personal statement. By 1200 the impact of the melting pot of knightly pan-European culture only intensified the need for something which would more personally identify the bearer of arms.

The solution – graphical charges – opened a vast, less geometric, array of images.

Anything seen or imagined could be represented either in its natural colours or in a fanciful, stylised version.

In the animate category, animals, birds, fish, reptiles, insects and monsters were all possibilities, as were divine or human beings.

As for inanimate objects, everything appeared from an anchor and an axe to a wheel and a woolpack by way of trees, plants, flowers and celestial objects.

As the graphical charge established itself as one of the key elements of identification, Heraldry began to reflect a sense of the period and society in which it was created. Further, its development over time clearly demonstrates heraldry’s infinite possibilities and power to adapt.

9

Of all the graphical charges in heraldry, animals have always played a large and significant role. And since heraldry is an art form it has never limited itself to actual creatures but let its imagination ran riot into the truly fantastical. A ‘winged sea horse’, for instance, is made up of the front half of a horse with wings stuck on plus the back half of a large fish. Consider also a heraldic sealion: half rampant lion, half fish. In their design of arms over the centuries, heralds have mixed and matched whenever they felt like it – and they still do!

During the fifteenth century supporters of the shield began to appear in the designs of Coats of Arms and larger animals were ideally suited to the job. In the Royal Arms a lion and a unicorn support the shield and in the City of London’s arms it is a pair of dragons.

Animals killed for sport and whose various qualities and strengths made them worthy opponents of their hunters soon appeared as graphical charges. All types of deer – stags, hinds, bucks, harts – were popular and were duly followed by bears, boars and wolves. Only later did creatures regarded as vermin – such as foxes, squirrels and rats– make their appearance.

10

Over the centuries heraldic devices have been displayed on flags of all sorts – banners, standards, pennons, guidons, gonfanons, and more. Some early, simple standards can be seen in the Bayeux Tapestry’s depiction of the 1066 Battle of Hastings, but it was the 13th and 14th century Crusades that formalised the use of military and national flags, principally as standards, banners and pennons.

Standards

Narrow, tapering, sometimes swallow-tailed and often fringed, their length reflected the rank of the owner - from four yards for a Knight to nine yards for the Sovereign. Divided lengthwise into two tinctures, they displayed the owner’s badge, heraldic devices, and occasionally his motto on a bend (but not his coat of arms) and appear to have been used solely for pageantry. No rules seem to have governed their display other than for English standards in the Tudor period when they were particularly popular. At that time standards always bore the cross of St George in the chief, followed by the device, badge or crest of the owner and then his motto.

Today, like the badge, a standard can still be granted to an owner of arms but its layout follows a regular format. The arms occupy the chief and the badge – sometimes with the crest – is placed on the fly which is crossed diagonally by the motto. The background of the fly can be either of a single tincture or of two set out in a shape echoing that of an Ordinary.

Banners

Square or vertically oblong, a banner was borne by Barons, Knights Bannerets, Princes and the Sovereign. It bore his arms and was his ensign and that of his followers as well as any military division in his command. A Knight Banneret, who ranked above other Knights, was created on the battlefield by the Sovereign personally following an act of extreme gallantry. In the ceremony a pennon had its points torn off, thus becoming a small banner or banneret. The Royal Banner (or Royal Standard’) belongs to the Sovereign. It flies wherever the Sovereign is in residence and appears on whatever mode of transport the Sovereign occupies (car, train, boat, plane).

Today, any armigerous person (possessor of Letters Patent granting a Coat of Arms) may have a banner and, although personal banners are rarely seen, local authorities and companies regularly fly their banners abovetheir premises. Quarterings and cadency marks and dierencing, (as they appear on the bearer’s shield) are allowed on banners but crests, badges, supporters, etc and impalements (two arms brought together on a single shield) are not.

Pennons

A smaller version of a banner, this too was narrow, tapering, and often swallow-tailed and fringed. Borne by a Knight immediately below the head of his lance, it was arranged to be viewed correctly when the lance was horizontal. It displayed the Knight’s badge, or his heraldic device and could repeat the main item on his shield.

11

In a pre-literate age, a badge expressed the allegiance of many men to a powerful individual, perhaps a feudal lord. He would display it on his personal standard (next to the cross of St George in chief), on the shields of his knights in tournaments, and on the livery of his horses.

In effect, it was the forerunner of a company’s logo. Unlike arms, badges are not hereditary, yet many have passed down the generations, coming to represent a family rather than an individual. The Feathers often refers to the badge of the Prince of Wales.

The Rose and Crown has particular significance. A rose was used as a badge by both the House of York (in white) and the House of Lancaster (in gold or red) during the ‘Wars of the Roses’ that culminated at Bosworth.

The victorious Henry VII, in overlaying one with the other, created the Tudor Rose, a royal badge used by English monarchs ever since.

Although not part of a coat of arms, a heraldic badge – sometimes more than one – is granted only to those who possess arms. And while arms are exclusive to one individual (and his heirs), a badge can be borne by any number of his followers. Today, badges can indicate 'belonging’ or ‘location’ and many sports, clubs, societies, and schools use them.

12

Originally, for the purposes of the tournament and the battlefield, heraldry was about the unique identification of those men who bore a coat of arms. Consequently, it has been heraldry’s abiding principal that no two coats are the same. Arms descend through the male line of a family and sons (‘cadets’) of an armigerous head of a family can use and display his arms. This immediately brings about duplication so here too heraldry demands a distinction – not only between the sons’ arms and their father’s but also between each of the son’s arms.

Very early heraldry used a number of methods to achieve this until the 16th century saw the present system of differencing for cadency allocate a special mark to each son in order of seniority.

Small and of any colour, cadency marks are normally added in the chief of the shield (the rules of tincture usually being upheld). An exception to this location is a quartered shield which combines two or more coats of arms. Here the mark is displayed centrally to overlap all four quarters – unless the mark relates solely to one of the coats in which case it is placed in that quarter.

The eldest son’s arms bear his cadency mark until his father’s death whereupon it is discarded and he reverts to his father’s ‘plain arms’ since he himself has become head of the family. Cadency marks for all other sons are permanent and descend as part of the arms to their own sons who duly add their own differencing for cadency.

Nowadays brothers rarely difference their arms during the life of their father, but often take up the mark when they become heads of families in their own right. Daughters are allowed to use their father’s arms but are omitted from the cadency system. Single women display their arms on a lozenge shape. Married women can now use a shield (with a lozenge for difference) which must include any cadency mark borne permanently by their father.

The mark must also be included when a daughter marries and transmits her arms to her husband. Her arms are then ‘impaled’ in the right-hand (sinister) half of her husband’s shield, alongside his own arms on the left (dexter).

If, when their father dies, one or more daughters have no brothers, they become heraldic heiresses. On marriage, their own family arms are placed in the centre of their husband’s shield in escutcheon of pretence.

13

From identifying a single person, heraldry moved to speak of the relationship with another party: an armigerous family (by marriage), or a notable special position (by appointment), or two or more lordships (by inheritance). In each instance his own arms would be ‘marshalled’ with those of the other party to produce a new design for his shield. A daughter, when single, is entitled to display her father’s arms on a lozenge but on marriage they are impaled with those of her husband on a shield. This is the simplest form of marshalling, the new shield being halved vertically to place his squashed arms into the dexter half and her squashed arms into the sinister.

Early heraldry impaled two coats of arms by dimidiation. Instead of each being squashed to occupy half of the new shield, they were cut vertically through their centres, one half of each being brought together to form the new, rather odd design. The children would display only their father’s arms. Arms descend through a family’s male line. Consequently, upon the death of her father, a daughter does not inherit his arms unless she has no brothers in which case she becomes an ‘heraldic heiress'. Here, upon marriage, her arms are marshalled with those of her husband in escutcheon of pretence: a small version of her shield placed in the centre of her husband’s shield. This arrangement is designed to show that, although the lady is armigerous in her own right, her husband pretends to the representation of her family. Upon her death, their children are entitled to display another form of marshalling: ‘quartering’ her arms with those of their father.